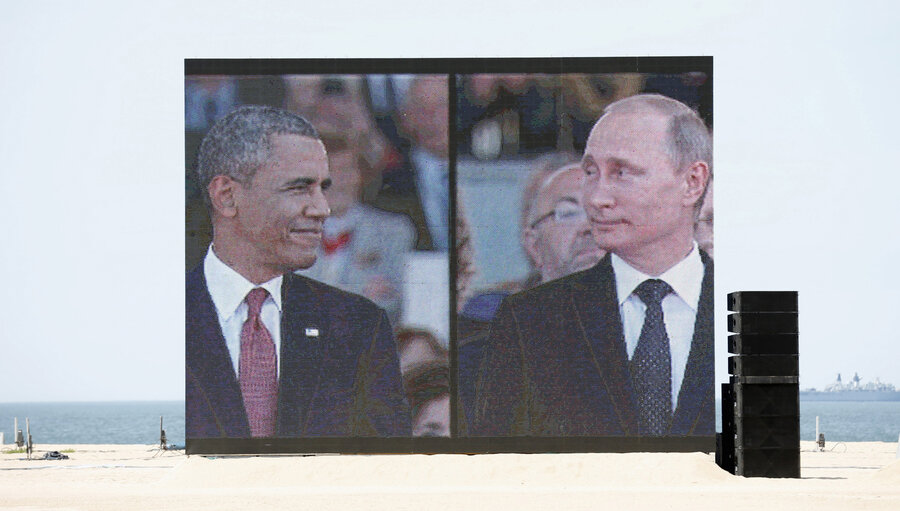

After blaming Russia for DNC hack, Obama weighs response

Loading...

The Obama administration's decision to blame Russia for cyberattacks against the Democratic National Committee may not be the last Moscow hears from Washington over the alleged hacks.

This week, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest confirmed that the US would follow up on last week's statement with a "proportional" response. "There are a range of responses that are available to the president and [President Obama] will consider a response that is proportional," he said.

But it's not yet clear what form that response will take – and Earnest did not elaborate on the options Mr. Obama is considering. Yet, the decision to attribute the attacks could give the US more leverage to respond to a swirl of suspected Russian-backed breaches connected to November's election using political, legal, or intelligence tools.

For weeks since the first leaked documents from DNC servers appeared on the antisecrecy sites WikiLeaks and DCLeaks.com, prominent Washington figures such as the Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D) and Rep. Adam Schiff (D) of California urged the White House to attribute the attacks.

"I think the Russians respect one thing and that’s strength – if they see an open door, that’s an invitation to do more," Mr. Schiff said on ABC's This Week earlier this month. "And I think we need to begin naming and shaming them, and work with our allies around the world who also have been hacked and interfered with by the Russians."

Now that the Obama administration has decided to name Russia, it faces the decision of whether to use tools such as sanctions, litigation, and hacking – or a combination of all three – to respond.

In three other instances, the Obama administration used cyberattack attribution – a complex process that combines detailed technical analysis of malicious software and computer activity with traditional intelligence gathering methods – to pursue charges against foreign hackers and lay down economic sanctions.

That trend started in 2014, when the Justice Department charged five Chinese nationals with ties to China's People's Liberation Army with allegedly stealing sensitive information from American companies. This year, the US charged seven Iranians for hacking into a small New York dam and flooding dozens of US banks with phony web traffic.

But none of the Chinese or Iranian hackers charged have appeared in an American court, and neither country has an extradition treaty with Washington, an agreement that allows foreign governments to surrender US fugitives. And while last week's joint statement released by the Department of Homeland Security and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence stated that the US government believes the Kremlin's "senior-most officials" authorized the DNC hack, but stopped short of specifically naming suspects. Some cybersecurity experts say that shows it's time to stop "naming and shaming" individual hackers.

"The US government and Western governments should stop putting a focus on people," says Robert M. Lee, chief executive officer at Dragos Security, a cybersecurity firm. "It offers the government a scapegoat to say those people are acting as rogue operators."

The White House also dished out economic sanctions against North Korea after a cyberattack on Sony Pictures Entertainment destroyed computers and wiped out servers in December 2014, causing millions of dollars in damages to the company.

But despite reports that US officials briefly considered similar punishments against Moscow this summer, the US has already authorized a rash of sanctions against Russia for its 2014 annexation of Crimea. With suspected Russian hacking activity ramping up around US elections, cybersecurity experts are looking beyond traditional tools to respond.

Though cybersecurity experts appear split over the range of possible responses, Jason Healey, a senior research scholar at Columbia University's School of Public and International Affairs, argues that the White House should look to established areas of international law to deter further Russian hacking activity.

One tool that Mr. Healey says could prove useful is invoking NATO's Article IV protection that calls on the 27 nation alliance to respond collectively to attacks against members by foreign powers, a move that might also stop potential attacks against upcoming elections in France and Germany.

"We should look to where we already have agreements,” he says. "We don’t need a new Geneva Convention for cyberspace, we already have the Geneva Convention. Just because something is cyber, it doesn’t mean you can use it to attack a hospital.”

When addressing potential responses with the press on Tuesday, Press Secretary Earnest did not indicate whether the activity would be private or public, but simply said that the White House was “not likely to announce ahead of time."

But just because that action may not soon become public, it doesn't mean that the US – or its allies – won't respond forcefully. In the wake of the Sony Pictures Entertainment attack, House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Michael McCaul (R) of Texas said an internet outage in North Korea was a response to the hack, but did not connect the blackout to the US.

Still, a former Defense Department official applauded the US for taking the decision deliberately – and urges caution in a response.

"There is this thinking of, 'They cyber'd us, why don't we cyber them?" says Michael Sulmeyer, director of the cybersecurity project at Harvard University's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. "But the truth is that we – meaning the United States – have certain vulnerabilities. Striking them back in the same way may not have the desired effect."

Paul F. Roberts contributed reporting for this article.