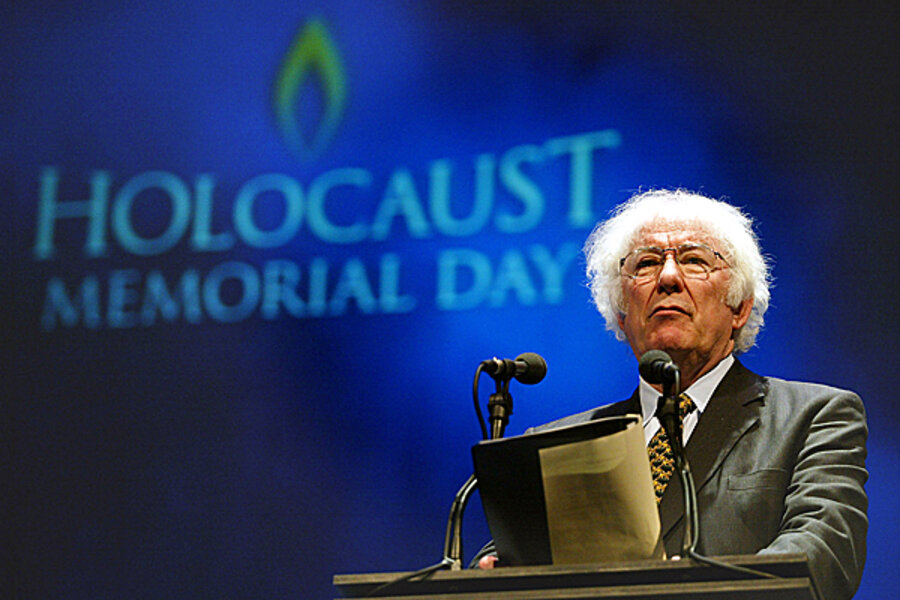

Seamus Heaney, a poet of peace, and conflict, and the earth, was among Ireland's greats.

Loading...

On a Friday afternoon in October 1995, the offices of the Swedish Academy, which selects the Nobel laureate in literature, received a warbled long-distance phone call from a man with an Irish accent.

It was the poet Seamus Heaney, and he had a simple question: Had he really won the Nobel Prize?

Mr. Heaney, who was on vacation in Greece at the time, had read a local news report the previous day saying he’d been awarded the $1 million honor. "Was it true?" he asked the Academy secretary calmly.

It was, and the prize helped Heaney – who died Friday in Dublin at the age of 74 – solidify his place as one of his country’s literary giants, placing him alongside fellow Irish Nobel laureates William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, and Samuel Beckett.

And despite the fact that he was nowhere to be found when his Nobel Prize was announced, Heaney’s accessible style as both a poet and scholar won him not only great critical acclaim but also an unusually widespread following during his five-decade career. By some estimates he was the world’s best-read living poet, The New York Times reports.

Poet Robert Lowell once described him as the “most important Irish poet since Yeats.” Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny said for the Irish he was “keeper of language, our codes, our essence as a people.”

Indeed, Heaney was a poet “rooted in the Irish soil," the New York Times wrote when he received his Nobel.

He has often written of the poet as a kind of farmer, digging and rooting, as though Ireland's wet peat were a storehouse of images and memories. At the same time, Mr. Heaney moves easily from the homely images of farm and village to larger issues of history, language and national identity, creating what he once called "the music of what happens."

Indeed, his poem Digging from the 1966 collection Death of a Naturalist begins:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging...

The poem ends: "Between my finger and my thumb/The squat pen rests./I’ll dig with it."

Born and raised on the family farm in County Derry, west of Belfast in Northern Ireland, Heaney’s life and career were also marked by the bloody sectarian conflict that sprawled across his most important writing years – and his own refusal to be circumscribed by it. As the BBC eulogized:

Born in Northern Ireland, he was a Catholic and nationalist who chose to live in the South. "Be advised, my passport's green / No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast the Queen," he once wrote.

He came under pressure to take sides during the 25 years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and faced criticism for his perceived ambivalence to republican violence, but he never allowed himself to be co-opted as a spokesman for violent extremism.

A well-known poem of his that expressed this ambivalence, Casualty, centers around an IRA bombing of a pub to punish it for defying an internal Catholic curfew the group had demanded after the Bloody Sunday massacre in Derry in 1972. An acquaintance of his, an elderly fisherman, was among the IRA's victims, "blown to bits" for being "out drinking in a curfew" and Heaney asks:

How culpable was he

That last night when he broke

Our tribe’s complicity?

‘Now, you’re supposed to be

An educated man,’

I hear him say. ‘Puzzle me

The right answer to that one.

Perhaps his most quoted lines come from a section of his poem “The Cure at Troy,” a verse adaptation of Sophocles' play "Philoctetes."

History says, don't hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

As the Associated Press reports, “scores of world leaders have borrowed those lines in their peacemaking speeches. John Hume, a Northern Irish republican who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1998, said Heaney's work offered "a special channel for repudiating violence, injustice and prejudice, and urging us all to the better side of our human nature."

In April 2013, Vice President Joe Biden quoted the poem at a memorial service for MIT police officer Sean Collier, who was killed by the alleged Boston marathon bombers during their attempted escape from the city.

In addition to publishing several volumes of poetry, Heaney was also a prolific translator of works ranging from the ancient Greek to the modern Polish.

"I have always thought of poems as stepping stones in one's own sense of oneself,” he told NPR in 2008. “Every now and again, you write a poem that gives you self-respect and steadies your going a little bit farther out in the stream. At the same time, you have to conjure the next stepping stone because the stream, we hope, keeps flowing."