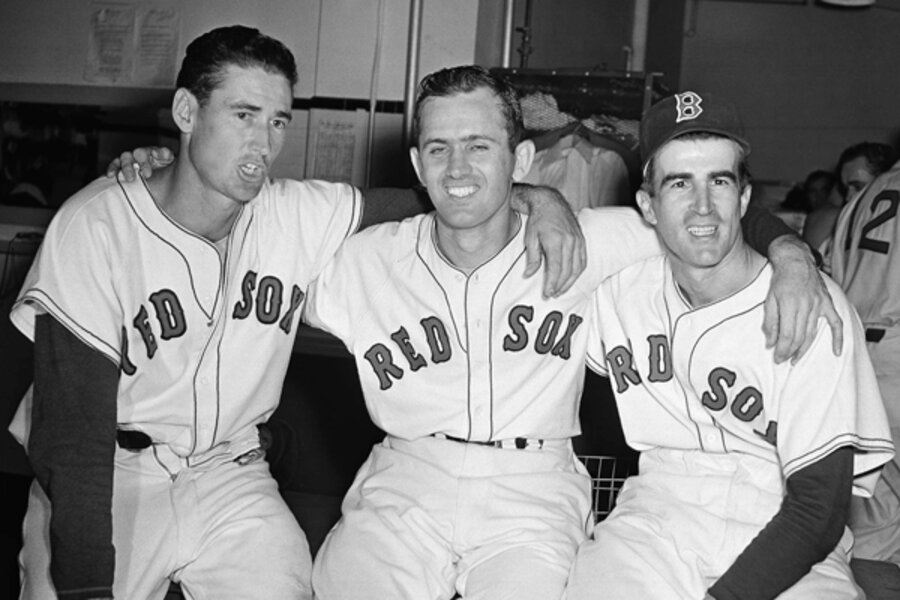

Remembering Johnny Pesky: the little big man of the Boston Red Sox

Loading...

Johnny Pesky, former shortstop for the Boston Red Sox who died Aug. 13 in Danvers, Mass., was a hit machine at the plate and a vacuum cleaner in the field. The skills of 5 ft. 9 in. Pesky and Phil Rizzuto, his 5 ft.6 in. counterpart on the New York Yankees, were compared during their careers almost as often as the press compared Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams.

During his first three years in the majors, Pesky pounded out 205, 208 and 206 base hits. And if the Red Sox hadn’t moved him to third base in 1948 after they traded for shortstop and power hitter Vern Stephens, Pesky might have had an outside chance to make baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Pesky’s three years in the US Navy during World War II also cost him a ton of base hits.

What made Pesky a permanent piece of baseball history was the seventh game of the 1946 World Series between the Red Sox and the St. Louis Cardinals.

St. Louis that year had a very fast and aggressive outfielder in Enos “Country” Slaughter. It was Slaughter’s daring base running, scoring all the way from first base after a single hit by teammate Harry Walker, that won the seventh game of the World Series for the Cards and made them World Champions.

Years later, sitting next to Slaughter in the visiting dugout about 40 minutes before an Oldtimers’ game at Dodger Stadium, I decided to ask Slaughter about the Pesky’s oft-cited delayed throw home on a relay from the outfield.

In Slaughter’s estimation, Pesky should never have been blamed by the press for holding the ball while Slaughter scored the winning run.

“Pesky got hit with a bum rap and I’ll tell you why,” Slaughter explained. “Before I even led off the last of the ninth inning, Cardinal Manager Eddie Dyer called me over for some instructions. He told me that if a situation developed on the bases where I thought I could score by taking a gamble that he’d accept the responsibility if I didn’t make it.

“Well, I got a hit and I was on first base with two out when I got the steal sign,” Slaughter continued. “So already I had a pretty good jump on the pitcher when Harry Walker hit this little floater into left-center field.

“The play was in front of me, so I could easily see that Boston outfielder Leon Culberson wasn’t going to catch the ball. In fact, the ball was still in the air when I came into second base, so I knew I could make it to third.”

At this point Slaughter claims that two things crossed his mind.

“I remember that Dom DiMaggio, who had a great arm but was injured, had been replaced by Culberson, who was not a strong thrower. And Pesky, who had gone out to take the relay like any shortstop would, naturally had his back to the plate and couldn’t see me.

“Since none of John’s teammates yelled to tell him where I was, I figured I’d gamble and try to go all the way home. I’d also caught a glimpse of Pesky out of the corner of my eye looking toward second base and probably wondering what had happened since Walker had done nothing more than a single.

“I’m sure when John turned back and saw me that he immediately threw to the plate. But by then I was already into my slide and by the time Red Sox catcher Roy Partee got the ball I was already across home plate. I know this: the play wasn’t close. I only slid because for me that was a reflex action.

“But I don’t see how anyone could possibly blame Pesky for what happened. He played it the way any shortstop would. I blame his teammates for not alerting him to the situation. And I never would have run anyway if DiMaggio had been in centerfield. Dom would never have thrown to the relay man. He’d have had the ball in the catcher’s glove while I was halfway down the line at third base.”

Although given the opportunity to manage the Red Sox in 1963 and 1964, Pesky lacked the temperament and discipline to deal with 25 different personalities. He seldom slept well after a defeat on the road and at home he probably read the papers too much. Pesky also served as a team executive and broadcaster during his nearly 70-year association with the Red Sox.

Johnny Pesky certainly had the baseball smarts for the job. Three times in his first season with the Red Sox, he pulled the hidden ball trick, catching Tommy Heinrich of the Yankees, Bill Zuber of the Washington Senators, and Glenn McQuillen of the St. Louis Browns off base.

In 10 seasons in the majors, Pesky collected 1,455 hits in 4,745 at bats for a lifetime batting average of .307. Hall of Famer Rizutto, even though he went to the plate 1,000 more times than Johnny, had only 133 more hits; ending up with a .273 career average.

Quick to praise others who helped him on his way to the majors, Pesky suggested that he might not have stayed if Ted Williams hadn’t shown him how to snap his wrists, the key to hitting line drives against all kinds of pitching.

Phil Elderkin carries Card No. 5 in the nearly 900-member Baseball Writers’ Association of America and is a former Monitor sports editor.