Creativity in motion: How painter Alex Katz partners with performers

Loading...

| Waterville, Maine

American artist Alex Katz has headlined more than 250 solo shows during his almost eight decades as a painter. His depictions of family celebrations and social gatherings, often rendered in vivid colors and on a large scale, are now iconic.

What has slipped under the radar is Mr. Katz’s close partnerships with performing artists, especially avant-garde theater ensembles, choreographers, and dancers.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAlex Katz sees the world through a lens of possibilities. An exhibit in Maine lifts the curtain on the famous artist’s designs for the performing arts.

But Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, is changing that with an exhibition focused not only on his painting, but also on his inventiveness as a designer of stage sets and costumes.

Mr. Katz doesn’t consider his stage designs a deviation. “Working on the theater and dance seemed very natural to me,” he comments in an email interview. “I didn’t think of it as much different from painting.”

Museums have been slow to embrace these less-traditional art forms and even to highlight friendships between artists working in different mediums.

“I can only surmise that this work has been considered tangential to Katz’s overall oeuvre and therefore of less interest and import,” says Maine art scholar Carl Little. But it’s more related than one might realize. “First and foremost,” he adds, “there’s the connection to his lifelong focus on the figure, which plays out with striking effect in many of his designs for dance and theater.”

Since first putting paintbrush to canvas almost eight decades ago, American artist Alex Katz has been featured in nearly 500 group exhibitions and headlined more than 250 solo shows around the world. His depictions of joyful family celebrations and pleasant social gatherings, often rendered in flat forms, vivid colors, and on a large scale, are now iconic.

In fact, his portraits of people mixing and mingling are such trademarks that a current retrospective devoted to the still-prolific painter at New York’s Guggenheim Museum is aptly titled “Alex Katz: Gathering.”

Also widely shown and highly recognizable are his numerous paintings of Ada, his wife of 64 years, as well as his luminous plein-air landscapes, often inspired during summers in Maine.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAlex Katz sees the world through a lens of possibilities. An exhibit in Maine lifts the curtain on the famous artist’s designs for the performing arts.

What has somehow slipped under the radar about Mr. Katz is his close collaborations with performing artists, especially avant-garde theater ensembles, choreographers, and dancers, most notably the Paul Taylor Dance Company.

But Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine, is changing that with an exhibition focused on this aspect of Katz’s illustrious career, celebrating not only his painting talent, but also his inventiveness as a designer of stage sets and costumes.

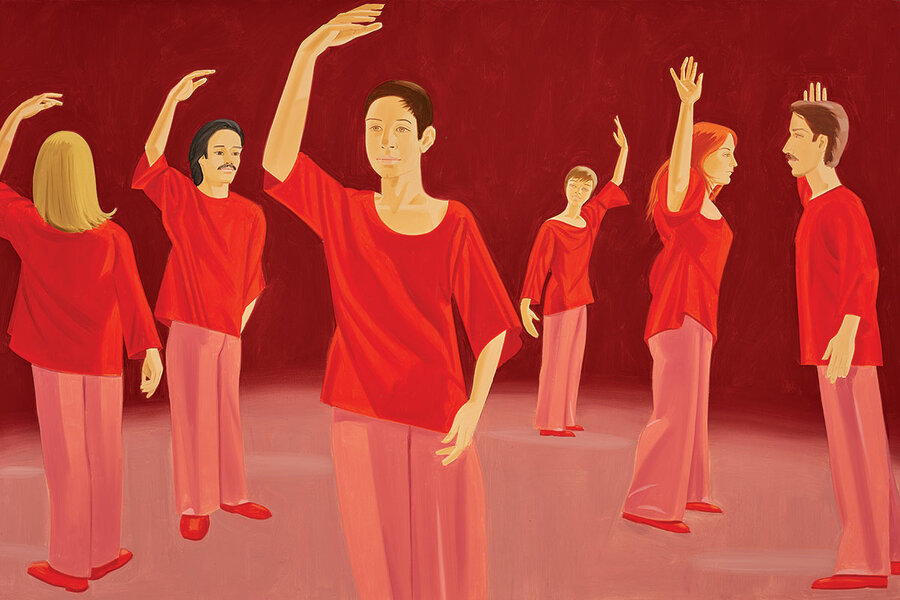

“Alex Katz: Theater and Dance,” on display through Feb. 19, is the first comprehensive museum exhibition of his highly collaborative, exuberant, and playful work with performing artists. It features a mix of mediums and materials, showcasing his explorations of dance and choreography in paint, but also with some never-before-seen sketches, collages, photographs, film, and “cutouts” – two-dimensional sculptures that informed his stage sets.

Mr. Katz didn’t consider this work much of a deviation. “Working on the theater and dance seemed very natural to me,” he comments in an email interview. “I didn’t think of it as much different from painting.”

Museums, however, have been slow to embrace these less-traditional art forms and even to highlight friendships between artists working in different media such as Mr. Katz and Mr. Taylor, says Levi Prombaum, Katz consulting curator who assisted curator Robert Storr on the Colby exhibit with guidance from the artist and his team.

“There’s a different consciousness now about the interplay with this medium,” says Mr. Prombaum. “The rise of performance art within the museum space is a recent phenomenon.”

Also at play could be the perception that this aspect of Mr. Katz’s career is somehow less significant than his contribution to modern realist painting.

“I can only surmise that this work has been considered tangential to Katz’s overall oeuvre and therefore of less interest and import,” says Maine art scholar Carl Little. But it’s more related than one might realize. “First and foremost,” he adds, “there’s the connection to his lifelong focus on the figure, which plays out with striking effect in many of his designs for dance and theater.”

Since the 1950s, Mr. Katz – who splits his time between Manhattan and Maine – has enjoyed a close relationship with Colby College Museum of Art, which gave him his first big break. “It originally started with Bill Cummings [a co-founder of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture], who was a fan and supporter of my work when no one else was,” explains Mr. Katz. “We were friends and he introduced me to Colby, and we seemed to fit. They needed something new at the time and I needed a place to show my work.”

Today, the museum, which specializes in American art, owns more than 900 Katz works, including 400 given by the artist himself. In 1996, Colby College opened a wing devoted to the collection.

“It makes sense,” says Mr. Little, “that Colby is the first arts institution to focus on these designs. The museum boasts an impressive collection of Katz’s art and is always finding new ways to showcase it.”

The latest exhibition does that, he says, noting that the rapport between Mr. Katz and Mr. Taylor, with its highs and lows, “makes for a compelling story.”

“How many artists initiate a new dance piece? And how many choreographers choose to be challenged by an artist’s vision?” he asks.

Mr. Katz, who once remarked to The New York Times that “Paul’s art is about astonishment and adventure,” looks back fondly on his work with Mr. Taylor. “I had ideas of staging; it wasn’t decorating,” he explains. “It was kind of fun to try them out particularly on Paul; we tried stuff that was insane.”

Since Mr. Taylor’s death in 2018, dancers have continued to model for the artist, and some of the most stunning portraits in the Colby exhibit were painted just in the past few years.

“With the painting, I’m more efficient than I was when I was younger,” says Mr. Katz, who still logs many hours in his Lincolnville studio, about an hour east of Colby on Maine’s Midcoast, and on the same property as his much-painted yellow 19th-century farmhouse.

He never grows weary of the legendary Maine light, which has attracted artists for centuries. Mr. Katz first became smitten in 1947, when studying at the Skowhegan school. But his ties to New York also run deep. He was born in Brooklyn to Russian immigrant parents, grew up in Queens, earned a degree at Cooper Union, and has been intimately connected to and influential in the city’s arts community.

So, dividing his time between his adopted state and his native New York suits him just fine. “I like painting outdoors and Maine is a great place to do that,” he explains. “There’s nice light and people seem to accept being a painter like being a carpenter. Growing up in Queens, being a painter was something weird. One place balances the other. I wouldn’t want to spend a whole year in either place.”

Another locale entirely is now on his radar: “I look forward to showing my new environmental water and grass paintings in Venice,” he says. Indeed, Mr. Katz’s latest work will be unveiled at next year’s Biennale in Venice, Italy.

Clearly, as Jacqueline Terrassa, director of Colby College Museum of Art, notes, “Alex Katz does not want to be bored.” She is awed, she adds, by how “he’s always challenging himself to try something new.”

That’s precisely what keeps him motivated day after day. Or as he puts it succinctly: “New thrills. They come with taking risks and that keeps me going.”