Scientists teach computers to learn simple ideas faster – like humans

Loading...

Researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and New York University have begun to teach computers an algorithm that mirrors the learning techniques practiced by humans – a big step toward reducing the amount of time needed for machines to learn and then practice new concepts.

"It has been very difficult to build machines that require as little data as humans when learning a new concept," Ruslan Salakhutdinov, an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Toronto, said in a news release. "Replicating these abilities is an exciting area of research connecting machine learning, statistics, computer vision, and cognitive science."

The researchers created a probability-based algorithm called a "Bayesian Program Learning" framework. Designed to be self-programming, the algorithm generated new code that produced a new output of the computer program the researchers wanted their software to learn in each successive variation. The results were published online Thursday and in Friday's edition of the journal Science.

This practice mirrors the way humans learn; most human beings require a few brief examples of a new concept before they latch onto it and understand.

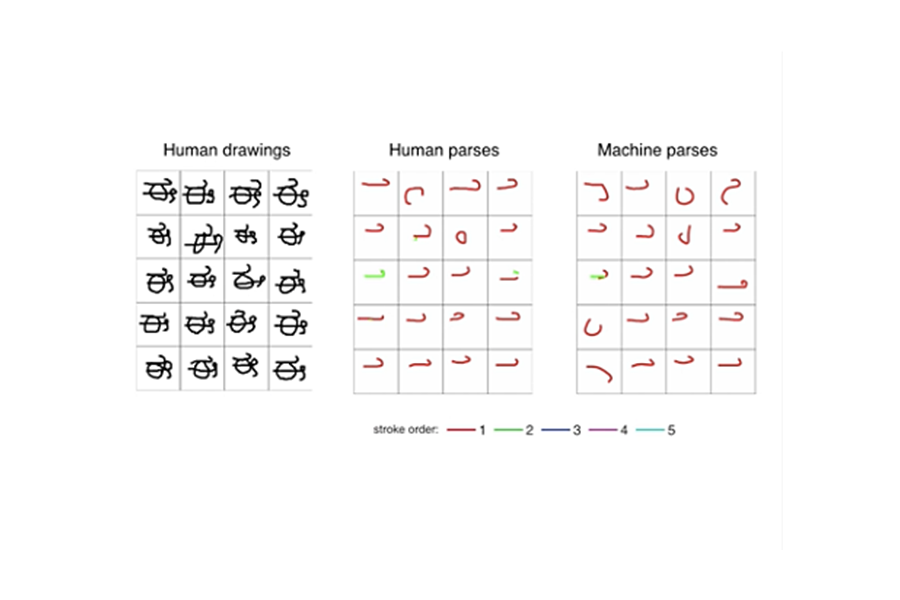

Over the course of the self-generating program, the software was able to identify correctly and to draw a handwritten character after seeing just one example. The researchers tested this accuracy by drawing on a database of the world’s written languages, including Sanskrit and Tibetan.

When the researchers showed the results of what their software had drawn to a panel of judges, asking them to compare the computer’s drawings to those made by humans, the judges were unable to distinguish between the humans’ drawings and the computer’s only 25 percent more than chance in each example.

The researchers are excited to explore what the results of this study could portend for other developments in artificial intelligence.

“We are still far from building machines as smart as a human child, but this is the first time we have had a machine able to learn and use a large class of real-world concepts – even simple visual concepts such as handwritten characters – in ways that are hard to tell apart from humans,” Joshua Tenenbaum, a professor at MIT in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the Center for Brains, Minds and Machines, said in the release.