Where do asteroids go to die? New evidence challenges old assumptions.

Loading...

Scientists have long believed that the demise of asteroids close to Earth happen in a fiery collision with the sun. But by examining nearly 9,000 near-Earth objects, or NEOs, an international team of researchers have recently found that asteroids and comets crumble long before they reach the surface of the blazing star.

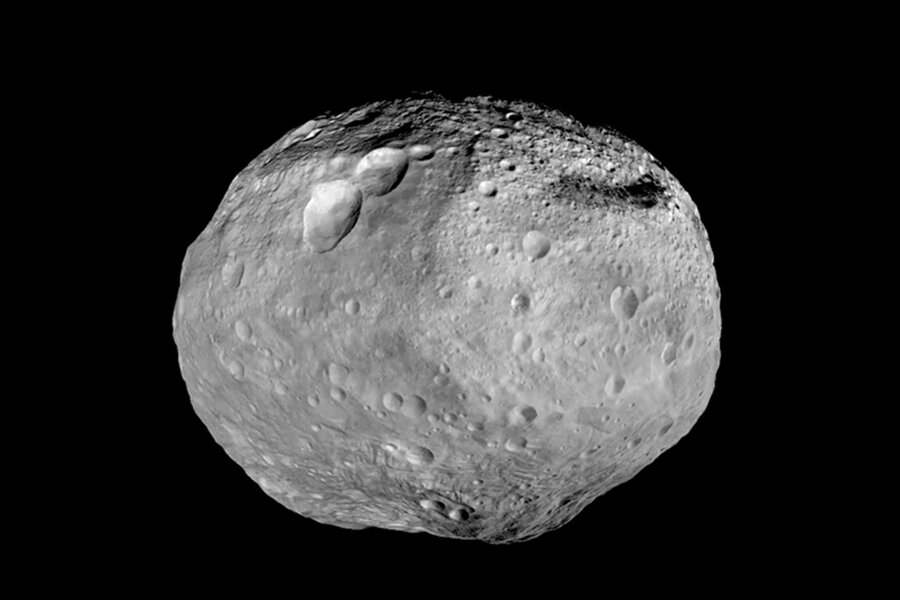

Residing in the doughnut-shaped asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, the NEOs that wander into our solar system typically follow their orbits without interference with Earth for billions of years. But occasionally, some are nudged by the gravitational forces of Saturn or Jupiter, and are led astray toward Earth.

So, scientists from Finland, France, the United States, and the Czech Republic got together a couple of years ago to formulate a model for the millions of NEOs to plan for future asteroid surveys and human space exploration missions.

According to Robert Jedicke of the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, an author on the study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, their model, which used more than 100,000 images acquired over about eight years by the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) near Tucson, Ariz., matched most of their data on NEOs – except in areas close to the sun.

Based on their calculations, there should be many more asteroids close to the sun than they actually found. For every 10 NEOs they expected to find within 10 solar diameters of the sun, only one was observed.

"If we weren't scientists, we might have said it's close enough, but something didn't feel right," Dr. Jedicke told The Los Angeles Times.

After another year of verifying their calculations, the team realized that it wasn’t their analysis that was off – it was the assumption of how asteroids disappear.

It turns out that asteroids are dying out as they approach the sun, but long before they would have collided. Although the authors are yet to be sure of how exactly the asteroids break up as they near the sun, they reached some other telling conclusions. Brighter asteroids, for instance, survived longer than dark asteroids, which absorb more light. And smaller asteroids disintegrate faster than bigger ones.

Their work also shed some light on the shooting stars that enter the Earth’s skies. The meteors are dislodged pieces of parent NEOs on their orbit but astronomers typically have trouble finding the latter. This study suggests that the parent asteroids may have already disappeared.

"Perhaps the most intriguing outcome of this study is that it is now possible to test models of asteroid interiors simply by keeping track of their orbits and sizes," lead author Mikael Granvik, of the University of Helsinki in Finland, said in a statement.

"This is truly remarkable and was completely unexpected when we first started constructing the new NEO model."