Alluring Enceladus: How a tiny moon has kindled scientists' imagination

Loading...

Last weekend, NASA’s Cassini probe made its last scheduled flyby of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Over the course of the previous 21, the joint United States-European mission turned a curious 300-mile-wide ball of ice into one of the most intriguing objects in the solar system.

In what could be its greatest legacy, Cassini has cemented the moon as a leading candidate to answer the question: Is there life elsewhere in the universe?

The probe has confirmed that a global ocean of liquid water exists beneath Enceladus’s icy surface, opening scientists' eyes to the possibility of oases for at least microbial life on tiny moons far from a planetary system's sun.

Before Cassini arrived, anyone suggesting the moon would host a global ocean “would have been laughed out of the room,” says Curt Niebur, with NASA's division of planetary sciences in Washington.

If such moons are potentially habitable here, why not moons orbiting planets at other stars? That question has prompted some researchers to hunt for moons orbiting extrasolar planets. If tiny Enceladus is any indication, the number of potentially habitable moons could be larger than the number of potentially habitable planets, some argue.

For now, Cassini's team is contenting itself with the treasure trove of data. The final close flyby brought Cassini to within 3,106 miles of Enceladus’s south polar region. It gauged the amount of heat rising through the ice in the areas that shoot plumes of water ice into space. That measurement is expected to provide clues about the geological processes involved.

Enceladus has captivated planetary scientists since the Voyager flybys of Saturn in November 1980 and August 1981. The moon was deeply embedded in one of Saturn's rings, known as the E ring, suggesting to some that somehow the moon was feeding the ring.

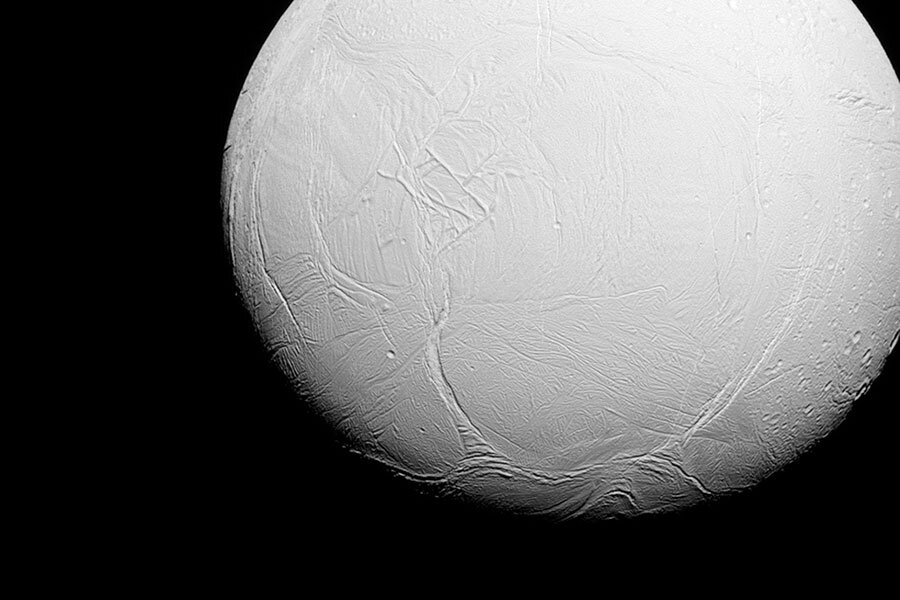

Perhaps the biggest surprise came with the discovery that a vast portion of Enceladus’s ice surface was geologically young – virtually crater free. Other areas had features that looked like fault scarps, long troughs, and bands made up of fissures and ridges – all pointing to action similar to plate tectonics on Earth.

When Cassini made its first series of passes, beginning in February 2005, it discovered the plumes of water vapor and various ices erupting along fissures in the southern polar region. Researchers estimated that these “tiger stripes” ranged from 10 to 1,000 years old. Temperatures in the region were significantly higher than expected.

With successive flybys, researchers found that the plumes contained organic compounds. Measurements also pointed to a moon that had a rocky core, with the ocean sandwiched between the core and ice crust. With additional data, they concluded that the ocean, initially described as regional, was global.

Minerals found in the plumes suggested that hydrothermal activity is occurring where core meets the ocean. That implies a source of nutrients and energy that could provide conditions similar to those at hydrothermal vents on Earth's ocean floor, which teem with life. Analyses of the plumes combined with chemical modeling on the under-ice ocean suggest that it is salty and not too acidic nor too alkaline to support life.

Researchers are still combing the data from Cassini's Oct. 28 trip through one of Enceladus’s plumes, looking for signs of molecular hydrogen. If it is present in sufficient amounts, it would be a smoking gun for the presence of hydrothermal activity at the core-ocean interface, researchers say.

Pull all of this together and Enceladus emerges as “a very odd, special place,” Dr. Niebur says.

Its potential to surprise hasn't been exhausted, he suggests.

For instance, the moon's heat source remains a mystery. Without it, the ocean would have frozen billions of years ago.

One idea involves tidal heating, which occurs as Saturn's gravity tightens and relaxes its grip during Enceladus's 33-hour orbit around the planet. But so far, the amount of heat Cassini has measured in the tiger-stripe region exceeds the amount that tidal heating would generate. Last Saturday's flyby is expected to help researchers figure out what is happening.

Clearly, Enceladus is on the short list of solar-system bodies with the potential to host life, Niebur notes.

Mars remains a “maybe” for extant life. Saturn's moon Titan tantalizes with liquid hydrocarbon oceans in its surface and a subsurface ocean, though it's thought to be twice as salty as the Dead Sea. At Jupiter, candidates include the moons Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede.

Even Venus has reemerged as a potential hot spot for simple life forms, dwelling among the planet’s clouds at heights where temperatures are far milder than the conditions on the surface – hot enough to melt lead.

None of these objects, however, surpass Enceladus as a place to look. It's relatively easy to reach. And despite the ice crust hiding a global subsurface ocean, no drilling is needed for an initial test for life's presence. The plumes represent a window on the environment below the ice and could carry evidence of biological activity.

Those measurements will await another mission, however. For Cassini, it’s now job well done.