Afghanistan's presidential election results are in and the trouble may be about to start

Loading...

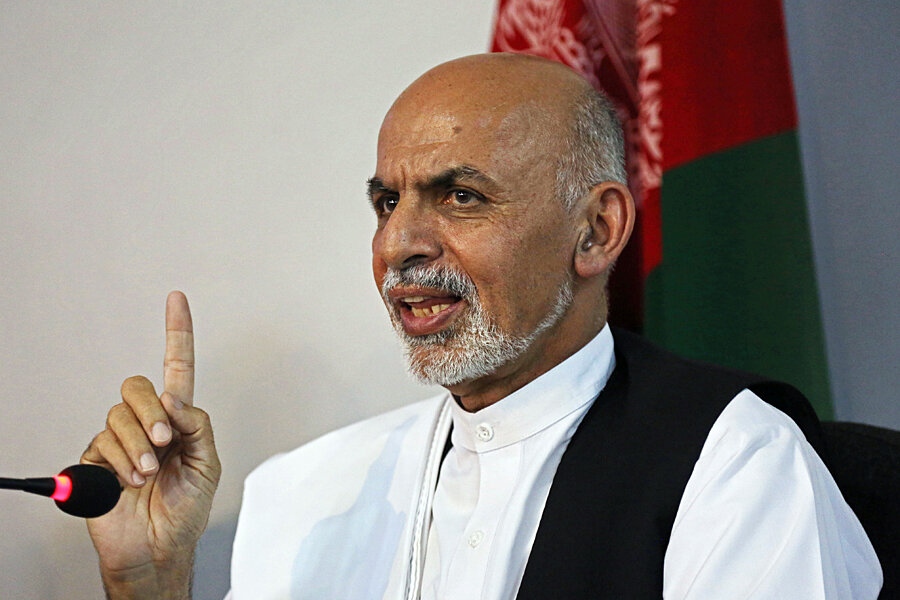

Provisional results of Afghanistan's presidential runoff election have finally been released. But while the numbers show former World Bank official and finance minister Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai a winner in a landslide, his opponent, Abdullah Abdullah, has been positioning himself for weeks to reject the outcome, complaining that he suspects electoral fraud and tampering by members of the independent election commission could have skewed the outcome.

Election results were delayed to allow for more auditing – something Mr. Abdullah welcomed – but in an interview on July 2 he also said that if fraudulent votes were winnowed out, the result would be "very different from what is perceived at this stage.” At that time, Mr. Ghani was felt by many to be in the lead.

The results released today give Ghani just under 4.5 million votes, 56.4 percent of the total, with Abdullah's share 3.46 million, or about 43.6 percent.

Afghanistan's election commission cautioned that the results aren't final. "The announcement of preliminary results does not mean that the leading candidate is the winner and [it is possible] the outcome might change after we inspect complaints," commission chief Ahmad Yousuf Nuristani said, according to Reuters.

The ethnic vote

It's hard to believe the results will not lead to increasing ethnic tensions, since Abdullah estimated that about 2 million fraudulent votes need to be thrown out. That could be enough to overturn Ghani's 1 million-plus vote lead at the moment (though some fraudulent votes certainly went to Abdullah as well). But it's hard to see Ghani and his supporters accepting a situation where a huge lead in the preliminary results ends up being overturned.

All of Afghanistan's elections since 2002, when the Taliban were overthrown by a US-led NATO coalition, have been heavily marred by fraud, from ballot box stuffing to double voting to rampant vote-buying by warlords aligned with various candidates. Afghanistan's voting patterns have run heavily along ethnic lines, with Pashtuns tending to vote for Pashtun candidates, Uzbek and Tajik voters tending to vote for candidates from their ethnic groups.

Evidence for the extent to which this vote turned on ethnic lines can be seen in the provincial breakdown. Ethnically mixed Kabul had a close race (with 52 percent of the vote going to Ghani), as did a few other provinces. But there were also enormous provincial landslides, as in the Tajik-dominated provinces of Parwan and Kapisa, where Abdullah won more than 86 percent of the vote, or in Pashtun-dominated provinces like Kandahar and Zabul, where Ghani took 84 percent and 92 percent of the vote, respectively.

In Juzjan Province, the home area of Ghani's running mate, Rashid Dostum, a feared ethnic-Uzbek warlord, Ghani took 81 percent of the vote.

Though Abdullah is the son of a Pashtun father and a Tajik mother, he's more closely identified with the Tajik minority, having fought against the Pashtun-dominated Taliban as a close adviser to Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic Tajik commander of the Northern Alliance who was assassinated by Al Qaeda just days before the Sept. 11, 2001 attack on the United States.

Given the heated rhetoric of recent weeks over fraud, the prospects for ethnically focused infighting among Afghans is going up. In practice that could mean violence among factions that are all nominally opposed to the Taliban – and are seeking their political fortunes in Kabul – could rise.

Current Afghan President Hamid Karzai, a Pashtun, is term-limited out. He supported the candidacy of Ghani, who is from his ethnic group and enjoyed strong electoral support in the country's Pashtun-majority south. Abdullah has said he would accept a losing outcome if he accepts that the vote was clean, and that's an option that remains open to him.

But it doesn't seem likely he'll take it, given recent comments from his camp. A little under two days after the polls closed in the middle of last month, a senior campaign official of Abdullah's said that "Karzai is quite happy everything is tied up.... They have engineered it in a way that goes far beyond the normal. It’s industrial-scale fraud,” according to The New York Times.

Fraud has been embedded into Afghanistan's political culture in the past decade. In Karzai's last presidential win, accusations of fraud were widespread – as was evidence of wholesale incompetence by the Independent Election Commission (IEC). That incompetence makes Afghan voters inclined to assume fraud even when it can't be proven, as Ben Arnoldy wrote at the time:

Afghans commonly question the independence of the IEC. The head of the electoral commission was appointed by Karzai without legislative or judicial oversight.

In Afghanistan's last round of national elections in 2004 and 2005 a lot of raw material was lost – ballot boxes went missing and registration data disappeared. The commissions archives became a scattered mess.

"There's no central repository for baseline figures, and that complicates the picture," says Candace Rondeaux, a senior analyst in Kabul with the International Crisis Group. On top of that, solid analysis "is very difficult" because of incomplete voter registration, problems with delivering election materials, and a lack of information about the security environment surrounding polling stations.

That lack of trust persists to this day. US and other NATO officials have generally taken a blasé attitude towards the lack of credibility of Afghan presidential and parliamentary elections, as I wrote in 2010.

In conversations with Western diplomats, Afghan election officials, and independent monitoring groups, it seemed everyone acknowledged that significant fraud was going to be inevitable in this election. The diplomats working with the NATO coalition there tried to put the best face on it, suggesting that elections were a good in and of themselves, because they said they would help get the Afghan people used to the forms of democratic politics, even if the governance outcome was largely the same.

The outsiders were more cynical, worried that fraud-marred elections to create an ineffective parliament amounts to a kind of democracy theater. In the critical view, such elections can convince people that democracy isn't for them.

To be sure, a shattering of the front opposed to the Taliban is in the interests of neither Ghani nor Abdullah – nor any of the political forces and warlords who support them.

A way to head off a crisis might still be found, and there's still time, with the inauguration of the next president scheduled for early next month and certified results not due out until July 22.

But for now, Abdullah's camp doesn't seem in a mood to back down. Mujib Rahman Rahim, Abdullah's campaign spokesman, told Afghanistan's TOLOnews. "We do not accept the results announced this evening by the IEC.