In Oman, a train-of-succession mystery: Who follows Qaboos?

Loading...

| Muscat, Oman

Sultan Qaboos, Oman’s ailing leader, is this small but wealthy nation’s prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, head of state, and commander-in-chief, all in one.

Everywhere in the Gulf Arab state, Sultan Qaboos looms large. His image greets visitors at the airport. His name adorns roads, schools, hospitals, ports, stadiums, and universities. The largest mosque in every major town is named after Qaboos – a distinction many Muslim communities reserve for the deceased.

Nearly every Omani has a story of when the sultan visited their town or village, aided their father, or personally opened a school or water plant. Loyalty to Oman is loyalty to Sultan Qaboos.

Now, with the childless 76-year-old sultan’s ailing health, attention has naturally turned toward his successor. But there’s a problem: No one knows who that would be.

Oman's stability is of importance to the region, and the world, because of the country’s location across the Strait of Hormuz from Iran. The two countries share control of the vital Gulf waterway, through which 20 percent of the world’s oil supply passes.

Western diplomats in the capital, Muscat, acknowledge that the Strait of Hormuz may be “the biggest prize” in the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and may be “the source of the next conflict” should Oman lose its delicate diplomatic balance between the two regional heavyweights.

Throughout his nearly five-decade reign as sultan, Qaboos, who rose to power in a bloodless coup after decades of turmoil and palace coups, has sought stability above all else. To prevent internal palace intrigues, outside meddling by regional powers, or infighting among Omani tribes, Qaboos has kept his succession plans vague.

The intricate maze of secrecy around the succession process, which includes a family council election and Academy Awards-style sealed envelopes, was designed, analysts and observers say, to ensure that Qaboos passed along stability as part of his legacy.

But will it work? All agree that the next sultan, whoever he is, will have a tall task at hand to win over a public that has only known, and benefited from, Qaboos. Even more challenging will be managing the future of Oman’s oil-dependent economy and preventing the social upheaval that some fear will accompany inevitably declining oil revenues.

Father and protector

Sultan Qaboos has long put himself front and center as father and protector of Oman.

With recently-discovered oil wealth, Qaboos pulled the country up from an impoverished backwater to a modern state and a major player on the Arab stage.

When he came to power in 1970, Oman was one of the poorest countries in the region. It had only three schools, and 66 percent of the adult population was illiterate, including 88 percent of women. One in every five children died before reaching the age of 5. The average life expectancy was 49.3 years.

Under Qaboos’s leadership, Oman’s GDP has grown from $256 million in 1970 to more than $80 billion. Today there are 1,230 schools, and adult illiteracy has plummeted to 5.2 percent. Oman is now home to 59 hospitals, and life expectancy has risen to 76 years.

Throughout Oman’s dramatic transformation, Sultan Qaboos has added a personal touch, being directly involved in matters ranging from regulations on how often Omanis should wash their cars to encouraging Omanis to open businesses.

The personal touch has left an imprint on Omanis, whose loyalty to Qaboos is genuine and palpable.

Jumaa bin Hassoun, a shipyard owner and builder of handmade Omani teak dhow ships, remembers the day the sultan urged him to return to his homeland from Kuwait and open up shop.

“The sultan sat here, spent all night. At the end of the night, before he left, he gave us a bag of money and told us to build,” bin Hassoun said from his shipyard in Sur.

Succession mystery

Experts say all the smoke and mirrors behind the naming of the sultan’s successor is by design.

Qaboos is believed to have been battling poor health since 2014, and has spent months at a time in Germany for treatment. He has rarely appeared at public events over the past three years.

According to experts, there are 85 individuals who are legitimate heirs to Qaboos – male descendants from the Al Said royal family with two Omani parents.

Under the current Constitution, a family council will select the successor within three days of Qaboos’s death. Should they fail to reach a consensus, Sultan Qaboos has left behind two sealed envelopes in two separate locations across the country, each bearing the name of his preferred successor.

Any one of the 85 could be named successor upon Sultan Qaboos’s passing.

“The ruling dynasty has a history of princes and siblings struggling over power and even killing each other. If a successor is very visible or known, there are many actors or parties that may pit members of the family against each other,” says Ahmed al Mukhaini, an Omani political analyst.

“If there is no apparent successor, in a way the system is more stable.”

Over the years, Qaboos has gone to great lengths not to favor one male relative over another, so as not to tip his hand.

Still, observers often name three favored candidates: Asaad, Shihab, and Haitham bin Tariq, the sultan’s cousins.

Until recently, few of them have had direct governing experience. On March 3, Qaboos issued a royal decree naming Asaad bin Tariq as deputy prime minister, a rare instance of involving the royal family in state affairs, and a signal to some analysts that Asaad, who is in his 60s, may be named the next sultan.

But both Western diplomats and analysts agree it is a “shot in the dark.”

Regional crossroads

Yet Qaboos’s penchant for secrecy is not just about his personal standing and domestic infighting. Observers say the system is a reaction to Oman’s troubled neighborhood, with the country bordering Saudi Arabia and the UAE and lying 35 miles away from the coast of Iran.

Qaboos has deftly maintained its neutrality over the decades while playing the various regional powers against each other. Oman maintains strong political and economic ties with Iran, an ancient trading partner, while having full and cordial ties with Iran’s bitter rival Saudi Arabia.

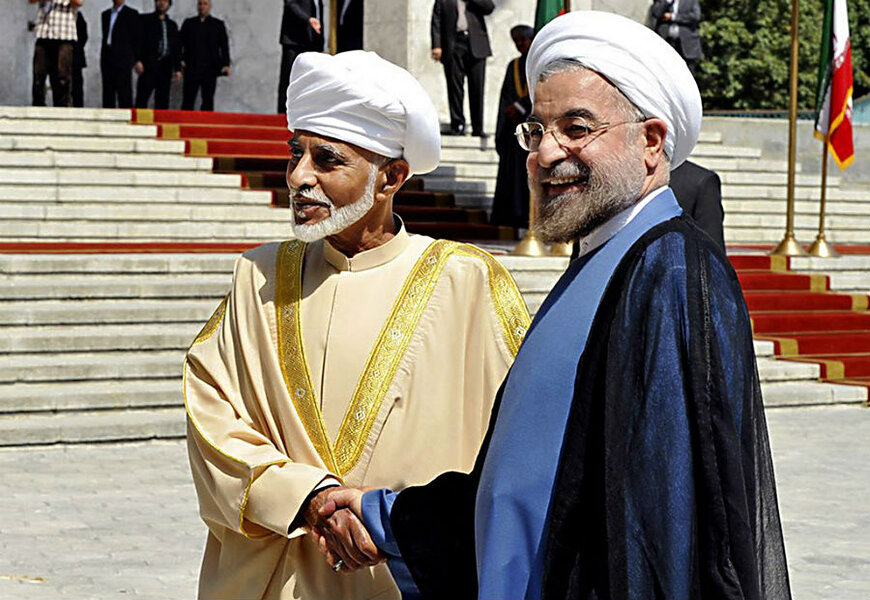

Long a geographic and political meeting ground between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran, Oman has used its position as a mediator between Gulf Arab countries, the West, and Iran, even helping to broker the 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

By naming a successor, Qaboos would open the door to the possibility of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, or Iran currying favor with the next sultan or using their wealth or intelligence agencies to coerce him.

“It is no secret that in the other GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] states, there are negative perceptions of Oman’s growing relationship with Iran,” says analyst Giorgio Cafiero, director of Gulf State Analytics, a Washington-based consulting firm.

“There is a good chance that other members of GCC, chiefly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, will attempt to pressure Sultan Qaboos’s successor in conducting a foreign policy more in line with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi and less so with Tehran.”

The secrecy also protects another important Qaboos legacy: balancing the various tribes and religious minorities that make up Oman in the state and security forces.

From courts to the local school board there is an even distribution of Ibadi Muslims, the tribes of the interior, Shiites, coastal merchants, and Omani expatriates from East Africa. A contender to the sultan’s throne may easily throw off this careful balancing act.

An economic challenge

Yet the secrecy surrounding Qaboos’s heir may keep the next sultan woefully unprepared for the country’s next potential crisis: the economy.

According to various studies, at current production Oman is set to run out of oil in 15 years.

Oman needs approximately $55 from the sale of each barrel of oil to pay for public sector salaries. When oil hovers or dips below $55 per barrel – as it has for a while – experts say Oman is in trouble.

In 2011, deadly protests erupted in Oman over a lack of jobs and corruption. Qaboos answered protesters with increased public hiring, higher salaries, and bonuses that the government is still paying for.

Analysts and Omanis privately worry how a new and inexperienced sultan, one who was not groomed for the position and eager to gain credibility, would react.

“With an increasing number of job-seekers, if the economy is not growing and they cannot provide projects, they will end up with a social bomb,” says Mr. Mukhaini.

“A new sultan would not have the same credibility as the previous sultan – it can upend the balance of things.”

Western diplomats have noted the increasing militarization of Oman’s security forces, and worry that any challenges to the next sultan’s rule, likely economically driven, may be met with force.

“If the next sultan is weak, he will likely rely heavily on the Army,” says a Western diplomat based in Muscat.

“All it will take is one rock thrown or one misunderstanding with protesters to light the streets afire.”