In Maldives presidential election, China and India are on the ballot

Loading...

| New Delhi

With hundreds of islands resting along critical Indian Ocean shipping corridors, the Maldives has become a battleground for the geopolitical rivalry between China and India.

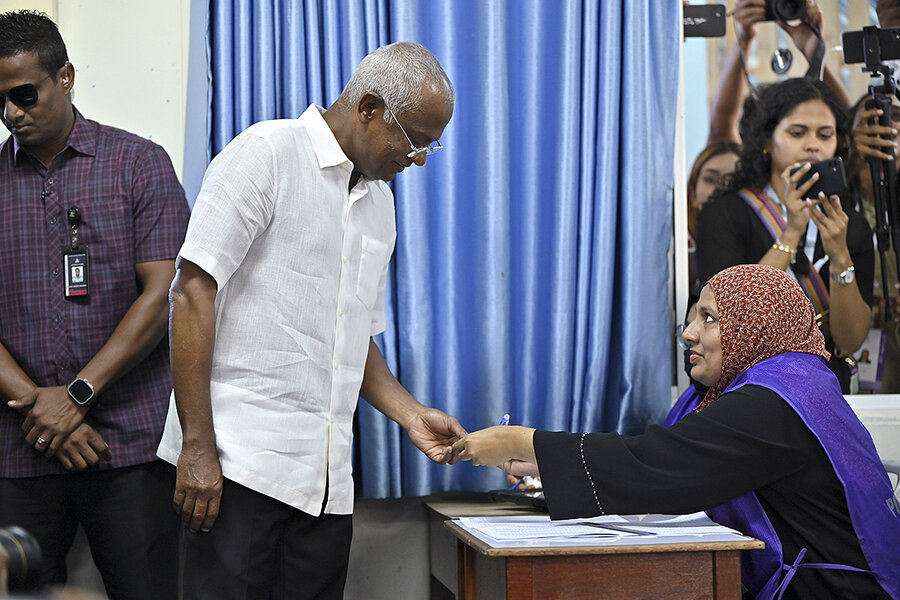

For years, Asia’s rising superpowers have vied for influence in the Maldives. The current administration strongly favors India, but many Maldivians worry about Indian military presence on their shores, as well as mounting foreign debt. In the first round of presidential elections this month, opposition leader Mohamed Muizzu took a surprise lead over incumbent President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, though neither secured enough votes to win.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the Maldives, voters have an opportunity to elect either a pro-China or pro-India president. Whoever wins, the future administration will need to balance foreign relations with Maldivians’ expectations of sovereignty.

As voters return for the Sept. 30 runoff, it’s clear that anti-India sentiment has bolstered the pro-China challenger, and with him, prospects for Maldives-China relations. Beijing and Delhi are watching the election closely, viewing it as a referendum on the archipelago’s foreign policy goals. For Maldivians, it represents a delicate balancing act with the country’s sovereignty on the line.

“Maldivians take a lot of pride in their sovereignty, even if it is a small country,” says Azim Zahir, an international relations lecturer at the University of Western Australia. An opposition victory would have “serious foreign relations implications,” including a “likely row between Malé and New Delhi,” but he notes that no government would attempt to completely sever ties with its neighbor.

When Maldivians head to the polls this weekend, they’ll vote for either incumbent President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih or Mohamed Muizzu, mayor of the capital, Malé. But the contest might as well be between India and China.

With hundreds of islands famous for white-sand beaches and luxury resorts, the Maldives sits along critical shipping corridors in the heart of the Indian Ocean. The archipelago’s strategic location makes it “an integral part of a free and open Indo-Pacific region,” according to the U.S. State Department, as well as a battleground for the heated rivalry between Asia’s rising superpowers.

For years, Delhi and Beijing have been vying for influence in the Maldives’ atolls. The current administration has strongly favored India, but many Maldivians worry about Indian military presence on their shores, as well as mounting foreign debt. Opposition leader Dr. Muizzu, whose conservative coalition opposes the growing security relationship with India, took a surprise lead over Mr. Solih in the first round of elections earlier this month, though neither candidate secured enough votes to win outright.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the Maldives, voters have an opportunity to elect either a pro-China or pro-India president. Whoever wins, the future administration will need to balance foreign relations with Maldivians’ expectations of sovereignty.

As voters return for the Sept. 30 runoff, it’s clear that anti-India sentiment has bolstered the challenger, and with him, the prospects for Maldives-China relations. Beijing and Delhi are watching the election closely, viewing it as a referendum on the archipelago’s foreign policy goals. For Maldivians, it represents a delicate balancing act with the country’s sovereignty on the line.

“Maldivians take a lot of pride in their sovereignty, even if it is a small country,” says Azim Zahir, an international relations lecturer at the University of Western Australia. An opposition victory would have “serious foreign relations implications,” including a “likely row between Malé and New Delhi,” though he notes that no government would attempt to completely sever India ties.

Ally shuffle

India is a “traditional friend of the Maldives,” says Amit Ranjan, an expert in South Asian politics and research fellow at the National University of Singapore. As neighbors, they share deep ethnic and linguistic links, and India was among the first to establish diplomatic relations with the Maldives when the island nation gained independence more than 50 years ago.

Ties flourished under Mohamed Nasheed, the country’s first democratically elected president, until opponents accused him of being beholden to Delhi. When Abdulla Yameen came to power in 2013, he reined in Indian influence and encouraged Chinese investment. Amid a flurry of infrastructure projects – including the country’s first inter-island bridge, the $200 million China-Maldives Friendship Bridge – the Maldives racked up a $1.4 billion debt to Beijing, even by conservative estimates. That’s about a fourth of the country’s gross domestic product.

Mr. Solih’s victory in 2018 saw the Maldives scale back Chinese contracts and embrace an “India First” policy, vowing to prioritize relations with its immediate neighbor. But now, as India positions itself as China’s geopolitical competitor, the pendulum of public sentiment appears to be swinging again.

“India First” or “India Out”?

There are about 75 Indian defense personnel stationed in the Maldives – a small figure, even for a nation of 520,000. Yet their presence – and the lack of transparency surrounding their deployment – makes locals like Aishath Liusha uncomfortable.

“Maldivians are always very close to India,” says the law student, who fondly remembers growing up in Malé with Indian teachers and nurses. But lately, she adds, “we are looking at Indians as a threat.”

Ms. Liusha is also worried about the Maldives’ growing debt to India, which after several housing and infrastructure projects and an influx of pandemic aid, now equals the money it owes China.

Proponents of the opposition’s “India Out” campaign accuse the current government of “selling off” the Maldives to India. Critics say such claims are exaggerated, and argue that the opposition has encouraged a paranoid, xenophobic view of India.

Hamdhan Shakeel, a senator with the Progressive Party of Maldives, says that’s not the goal. To him, it’s an issue of balance.

“India will always remain as the closest partner to the Maldives. However, at the same time we must also acknowledge China as a close partner,” he says via WhatsApp. “To say that one is more important than the other is to disservice their contributions to the development of Maldives.”

He says the opposition coalition “will maintain an ‘India first’ policy in terms of regional affairs, but not ‘India only’ policy as currently practiced.”

Exacerbating this debate over foreign influence, according to Dr. Ranjan, is the escalating power struggle between India and China, which are currently locked in a tense border standoff. While resource-rich nations like Saudi Arabia can navigate tensions and safeguard their sovereignty more easily, he says countries like the Maldives and Nepal are feeling the pressure to pick a side.

“When you are a small country, it is very difficult for you to manage this balancing thing for a long time,” says Dr. Ranjan.

Election prospects

Since the Sept. 9 vote, the Maldives has seen a surge in voter re-registration, which some interpret as a favorable sign for the ruling party. The opposition has urged election watchers to investigate.

As both candidates attempt to muster late-game support, former President Nasheed has emerged as a possible kingmaker. Mr. Nasheed, who was seen as being too close to Delhi during his tenure, has been critical of Mr. Solih and even hinted at endorsing the pro-China Dr. Muizzu. If that happens, Dr. Ranjan says Mr. Nasheed “may become a bridge” between India and the new government formed by the opposition.

Former President Yameen, who jailed political rivals and curtailed freedom of speech, has already thrown his weight behind Dr. Muizzu, giving some undecided voters pause. Ms. Liusha worries about the return of authoritarian practices, but Mr. Solih has also failed to deliver on his campaign promise of weeding out corruption.

When it comes to presidential candidates, “we are in a situation where we have to go for a lesser evil,” says Ms. Liusha.