In remote villages, typhoon aid comes from far-flung Filipino families

Loading...

| Hernani, the Philippines

Jade Abug was speechless as he approached the village of Batang on the back of a truck. The 23-year-old Philippine airman grew teary-eyed as he climbed down and walked to what was left of his childhood home.

The two-story wood house balanced precariously on its slanted, skeletal frame. Even the lightest gust caused it to creak. And it was sheltering over 20 of Abug's relatives who were desperate for the food and water that he was bringing from distant Manila.

“It’s so sad,” Mr. Abug said. “In the blink of an eye, it’s all gone. There’s nothing left.”

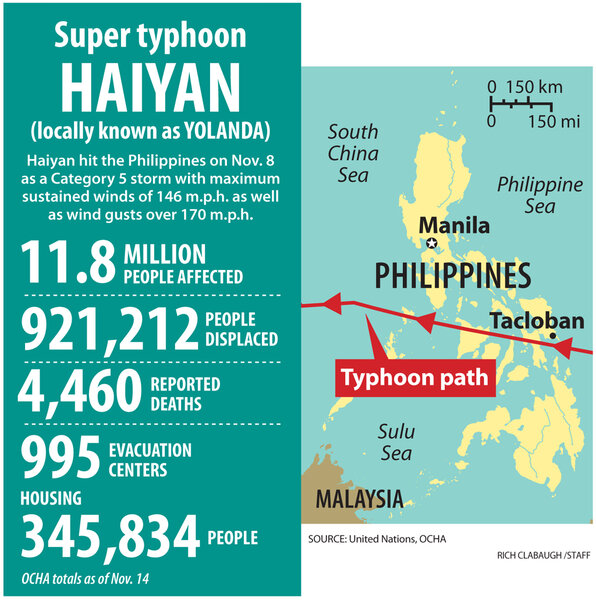

Across the towns and villages on Leyte and Samar islands that were hit hard by Typhoon Haiyan, family members have tried to fill in the void until humanitarian relief efforts can make contact. The Philippines government says in total about four million people have been displaced by the storm and 2.5 million still require food aid. Yesterday, the head of UN disaster relief efforts visited the town of Guiuan in Eastern Samar, about 40 kilometers outside of Batang, and said that the coastal communities still have not yet received food aid, according to Reuters.

After a quick look around and a few hellos, Abug unpacked the supplies he had brought with him on his 26-hour journey: crackers, canned sardines, instant noodles, and one and a half liters of water.

Abug knew it wasn’t much. He just hoped it would help hold over his family until more food arrived. Relief efforts have been slow to arrive. In their absence, many families have relied on — and prayed for — far-flung relatives to come to their aid.

Abug was the last of seven relatives to travel last week to Batang from the Greater Manila Area. The others had driven there non-stop in a crammed van, making ferry crossing between islands, while Abug rode an Air Force plane to Tacloban before heading north by truck and arriving Saturday. Like other relatives, Abug took a 10-day leave for the trip.

With more than 700 mouths to feed, food in Batang is desperately needed, said Captain Marino Baguan, the village’s top official. Haiyan destroyed the village’s primary food sources. It flooded rice fields, toppled coconut trees, and shattered fishing boats.

“All the animals died,” Mr. Baguan said, including the village’s 15 water buffaloes. “Without more support, I do not know how long our food will last.”

John Ang, a Philippine Red Cross volunteer who had traveled to Batang to assess the damage, said Saturday that help was on the way. But trucks had been held up by a bottleneck at Matnog Port, one of the main crossings to the island of Samar. More than 200 vehicles formed a line that stretched for miles outside Matnog Port over the weekend.

"We've had people here for a couple of days and I hope that by tomorrow we will be reaching a number of those coastal communities where they still have their boats but we haven't been able to get to them with food so we urgently want to get to them with food," Valerie Amos, the UN disaster chief, said in Guiuan Tuesday.

Ang said he worried that many of the coastal towns in Eastern Samar were being overlooked because of their relatively small populations in comparison to cities such as Tacloban and Guiuan farther south.

“All the teams from Manila when they pass through this place think it’s just a small community,” he said. “But it had hundreds of homes. And the destruction here is much worse.”

Batang, a neighborhood of Hernani, was reduced to rubble when Haiyan barreled through 11 days ago. The storm flattened hundreds of wooden huts and the village's lone chapel. Only a handful of concrete buildings remained intact.

On Saturday, villagers scavenged through piles of debris in search of materials to build temporary shelters. They were also looking for bodies. Baguan said 19 people were still missing in Batang as of Saturday. Many villagers assumed the worst, and the confirmed death toll stands at nine.

Among the victims were one of Abug’s uncle and his two-year-old cousin. Above their sand-covered graves sit crosses made from salvaged wood.

“Christmas isn’t going to be the same this year without them,” Abug said. “I’m shocked. I never imagined this could happen to us.”