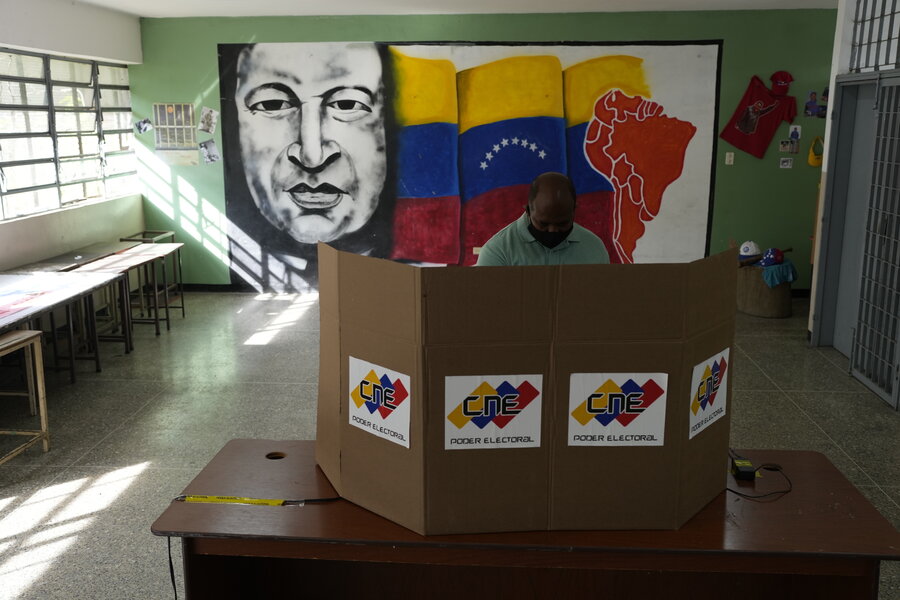

Venezuelans cast regional ballots under international scrutiny

Loading...

| Caracas, Venezuela

Under the scrutiny of international observers, Venezuelans cast ballots for thousands of local races in elections that for the first time in four years included major opposition participation, a move that divided the already fractured bloc adversarial to President Nicolás Maduro.

More than 130 international monitors, mostly from the European Union, fanned out across the South American nation to take note of electoral conditions such as fairness, media access, campaign activities, and disqualification of candidates. Their presence was among a series of moves meant to build confidence in Venezuela’s long-tarnished electoral system, but turnout was still low.

“It gives me a little more confidence that they respect our right to vote and respect our vote because we want this to change,” hospital worker Pedro Martinez said of the observers’ work. Yet he understood why few people were in line at the polling center in an eastern Caracas neighborhood that typically votes against Mr. Maduro and his allies: Opposition leaders “fight amongst themselves.”

“That division in the opposition leads to few people [voting],” said Mr. Martinez, for whom his country’s economy and health care services were top of mind this election. “The opposition has to work very hard to gain people’s trust.”

More than 21 million Venezuelans were eligible to vote in over 3,000 contests, including for 23 governors and 335 mayors. More than 70,000 candidates entered the races.

Historically, voter turnout has been low for state and municipal elections, with abstention hovering around 70%. The regional contests normally don’t attract much attention beyond the country’s borders, but Sunday was different because of the steps taken by Mr. Maduro’s regime and his adversaries leading up to the election.

The National Assembly, with a pro-Maduro majority, in May appointed two well-known opponents as members of the National Electoral Council’s leadership, including an activist who was imprisoned over accusations of participating in actions to destabilize the government. It is the first time since 2005 the Venezuelan opposition has more than one member on the board of the five-person electoral body.

In August, representatives of Mr. Maduro’s government and allies of opposition leader Juan Guaidó began a formal dialogue, guided by Norwegian diplomats and hosted by Mexico, to find a common path out of their country’s political standoff. By the end of that month, the opposition’s decision to participate was announced. Mr. Maduro’s representatives for months had also had behind-the-scenes talks with allies of former opposition presidential candidate Henrique Capriles.

Mr. Maduro agreed to allow a large presence of international observers, satisfying a demand from the opposition. The EU, motivated by the talks in Mexico, accepted the invitation of Venezuelan officials. But those talks were suspended last month following the extradition to the United States of a key Maduro ally.

It is the first time in 15 years that EU observers are in Venezuela. In previous elections, foreign observation was essentially carried out by multilateral and regional electoral organizations close to the Venezuelan executive. They are expected to release a preliminary report Tuesday and an in-depth look next year.

Millions of Venezuelans live in poverty, facing low wages, high food prices, and the world’s worst inflation rate. The country’s political, social, and economic crises, entangled with plummeting oil production and prices, have continued to deepen with the pandemic.

“I vote for Venezuela, I don’t vote for any political party,” Luis Palacios said outside a voting center in the capital of Caracas. “I am not interested in politicians, they do not represent this country. I think Venezuela can improve by participating because, well, we don’t have any other option anymore.”

Regardless of turnout, Sunday’s elections could mark the emergence of new opposition leaders, consolidate alliances, and draw the lines to be followed by Mr. Maduro’s adversaries, who arrive at these elections decimated by internal fractures, often rooted in their frustration at not being able to knock from power the heirs of the late President Hugo Chávez.

“What we are going to see is a fight for second place because second place will symbolically mean which opposition [the government believes] should be stopped more, that will have a weight,” Félix Seijas, director of the statistical research firm Delphos, said ahead of the election. He added that the results will show who ultimately “is the second force” of the country, and which segment of the opposition represents it.

Mr. Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores in televised messages after casting their ballots urged Venezuelans to go out to vote.

He said the election “will strengthen political dialogue, it will strengthen democratic governance, it will strengthen the capacity to face problems, find solutions.” But in the same remarks to reporters, he said the dialogue with the opposition cannot resume at the moment.

“It was the government of the United States that stabbed in the back the dialogue between the Bolivarian government of Venezuela and the extremist Guaidosista opposition of Venezuela,” he said, referring to Mr. Guaidó, whom the U.S. recognizes as the legitimate leader of the country.

“They have to answer for that kidnapping and the moment we believe there are conditions we will announce it to the country,” Mr. Maduro said, referring to the detention and extradition of his ally Alex Saab, which he considers a kidnapping, arguing Mr. Saab was a diplomat when he was stopped in Cape Verde.

The U.S. has imposed economic sanctions on Venezuela’s government, Mr. Maduro, and some of his allies, including Mr. Saab. The leadership change in the electoral council and the government’s participation in the dialogue in Mexico were seen as measures meant to seek improved relations with the Biden administration.

Mr. Guaidó on Twitter characterized the election as an attempt from Mr. Maduro “to relativize and normalize the crisis.”

This story was reported by The Associated Press.