Briefing: How Mexico is waging war on drug cartels

Loading...

| Mexico City

Who are the main players?

The Gulf Cartel, whose territory, along with that of Los Zetas (see below), extends from the US border to the Yucatán Peninsula, was until recently Mexico's most powerful drug-trafficking organization. But government pressure, particularly over the past two years, has weakened it. The former leader, Osiel Cardenas Guillen, was arrested in 2003 and extradited to the United States in 2007. The group is headquartered in the northern state of Tamaulipas, where it has long smuggled drugs into Texas, employing Los Zetas as its ruthless, private army. Along with the Sinaloa, Beltran Leyva, and Zetas groups, it is a main player in the cocaine trade.

Los Zetas grew out of the military special forces deserters that Gulf Cartel leader Mr. Guillen recruited in the 1990s as his private security detail. They eventually became the paramilitary arm of the group, then split off in late 2007 or early 2008. The relationship between Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel is unclear today, since the two are believed to still work together in an organization referred to as "The Company." The group, led by Heriberto Lazcano, is organized as a formal drug-trafficking organization, but Los Zetas also subcontracts work to other cartels. New members are recruited from federal and local law enforcement agencies, as well as Mexican and Guatemalan special forces. Los Zetas are increasingly suspected of involvement in kidnapping, extortion, and immigrant smuggling.

The Sinaloa Cartel, along Mexico's Pacific coast, is reputedly led by fugitive Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, Mexico's most-wanted man. He is also on Forbes magazine's 2009 Richest People list with a net worth of $1 billion. Drug trafficking over the past decade in Mexico was dominated by the Sinaloa and Gulf organizations, but the weakening of both has led to splintering, giving other groups space to grow.

While it's in better shape than the Gulf organization, the Sinaloa group until recently was allied with the Beltran Leyva and Juarez cartels (forming the Sinaloa Federation), but both have split off. It is believed to be the most active smuggler of cocaine today; its reach extends into Central and South America.

The Vicente Carrillo Fuentes organization/Juarez Cartel has long reigned over Ciudad Juárez, Mexico's most violent city. Of all the executions in 2008, one-quarter of them occurred in this border town. The Juarez Cartel smuggles cocaine and marijuana into El Paso, Texas, and beyond. But their influence has waned since the late 1990s.

Today, the bloodshed in Juárez is blamed not only on a power struggle between the Juarez cartel and their former allies of the Sinaloa Federation, but also between the Sinaloa and Gulf cartels, which are vying for control into the US market at the border.

Ten years ago, the Juarez and Tijuana cartels dominated drug trafficking in Mexico, says Stephen Meiners, a Latin America analyst at the global intelligence company Stratfor. But the influence of the Tijuana Cartel, dominated by the Arellano Felix family, has diminished considerably, particularly due to intercartel fighting, which accounts for most of the violence in Tijuana today. In April 2009, the Mexican attorney general's office declared the collapse of the cartel with the arrest of Isaac Godoy Castro, or "El Dany."

The Beltran Leyva Organization has become one of the most powerful drug traffickers in Mexico since splitting from the Sinaloa Federation in 2008. It controls routes in the states of Durango, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Sonora, and Sinaloa. The group has ordered executions of high-ranking officials, according to Stratfor, including the acting federal police director, Edgar Millan Gomez, in Mexico City last year.

La Familia, a Michoacán-based organization, is an emerging group. Their activities are still largely contained to the state, but officials note a trademark of ferocious retaliation. Last month, they shot into police stations across Michoacán in revenge for arrests of their members. They first organized as a vigilante group opposed to drug gangs and kidnappers. But with the vacuum left by the splintering of the dominant players, they have quickly become immersed in the trade. They are considered the nation's biggest traffickers of methamphetamine.

What are the risks of using soldiers in the fight instead of police?

The Calderón administration has deployed 45,000 troops across the country. Upon taking office, the president said that using the military was a temporary solution while police and judicial reform to root out corruption was carried out. But many fear that by putting soldiers in contact with traffickers, they are being exposed to the same corruptive forces that have entangled so many law enforcement officials.

The reputation of the military, which has ranked as one of Mexico's most sterling institutions, is also being battered, with the national human rights commission condemning alleged abuse. Investigating abuse claims in July, Human Rights Watch urged the United States to withhold some funding from the US drug-aid package called the Merida Initiative, concerned over alleged human rights violations – including torture, rape, and arbitrary detentions – not being properly tried in civilian courts.

What progress has President Calderón made dismantling cartels?

Since Mr. Calderón took office in December 2006, more than 11,000 have been killed in cartel-connected deaths, according to running tallies in the local press. The attorney general's office says that 9 of 10 victims are members of organized-crime groups. Most violence has occurred in the state of Chihuahua. The government says violence is the unwelcome result of its clampdown: Groups have splintered, creating more turf wars.

Others are not convinced.

The Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego analyzed the number of drug-related killings in the first six months of 2009, comparing it with the last six months of 2008, and found a 5 percent drop. "There has been an enormous expenditure, deployment of military forces, and to only have a 5 percent drop in record levels of violence doesn't really sound like success," says David Shirk, the director of the Trans-Border Institute. "There have been key traffickers taken down, big busts, major blows to different narcotrafficking organizations, but the net result has not changed."

But violence is not the only measure used to gauge progress. Drug organizations have moved into new territory, such as extortion and kidnapping for ransom – a sign to many that it is harder to traffic drugs in Mexico today than three years ago.

"There are fewer drugs coming in and drugs are harder to get out, but you still have these large, powerful criminal organizations looking for ways to supplement their incomes," says Mr. Meiners.

Another way that success is measured is the price of cocaine. At the end of last year, the US noted a doubling of cocaine prices in two years, attributed in part to a decline in supply. The US State Department estimates that 90 percent of cocaine in the country enters through Mexico.

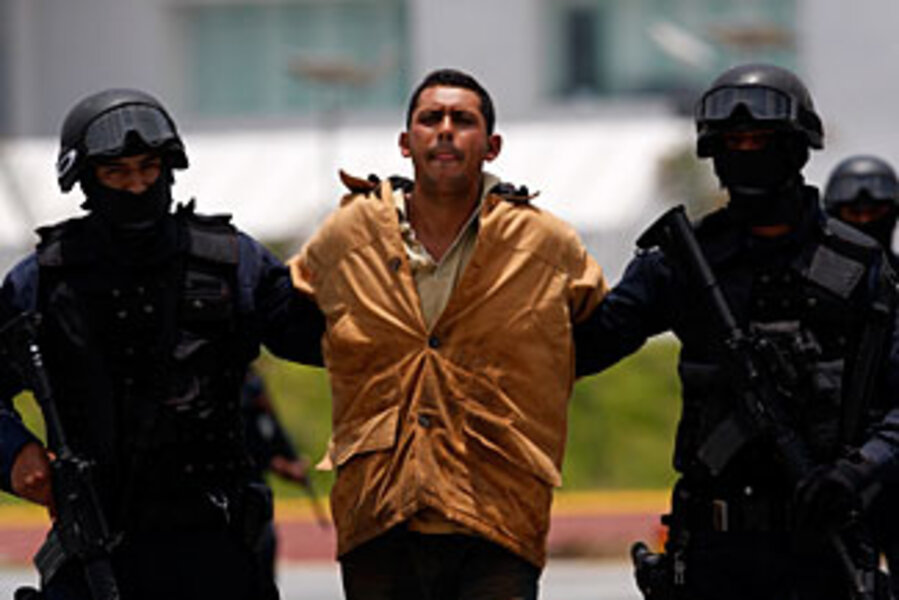

The Mexican government has also made record drug seizures and arrested more than 50,000 drug-trafficking suspects, including officials at the highest levels. It has maintained from the start it will never back down from fighting organized crime.

How have the US and Mexico cooperated in fighting trafficking?

Mexico has contended that its success in dismantling organized crime is hampered by a thriving US demand for drugs. Tension spiked this winter after a Pentagon report warned that Mexico could become a "failed state." While violence has alarmed many – prompting the governor of Texas to ask National Guard troops to bolster security for his state – there is no evidence that violence is significantly infiltrating US cities.

But Mexican and US officials say they are cooperating as never before: Authorities are working toward more intelligence sharing, the US is tracking gun flows, and Mexico is extraditing alleged traffickers to the US at a record pace (with 95 criminals sent to the US last year, according to the US Drug Enforcement Administration).

The signature has been the 2007 Merida Initiative. The aid, which also benefits Central America, includes money for surveillance equipment and training. The $1.4 billion package, to be disbursed over three years, is controversial in the US, as some condemn Mexico for its faulty record on holding the military accountable for human rights violations.

Is Mexico a safe place to travel?

Tourism has been battered over the past year – largely by swine flu but also by drug violence. Some colleges urged students to skip spring breaks in Mexico. Violence is largely among rival traffickers, or targets journalists, police, or the military. But the State Department issued an alert in February warning of "large firefights in many towns and cities across Mexico." That sort of violence has largely been limited to the border, including Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez.•

Research: Sara Miller Llana, Adrian Mitescu, Leigh Montgomery.

Sources: Mexican Attorney General's Office, Congressional Research Service, Stratfor, Trans-Border Institute/University of San Diego.