Ferguson: People unite to meet children's needs, from food to counseling

Loading...

When the students of Missouri’s Ferguson-Florissant School District head back to class on Monday – an opening postponed from Thursday – they’ll be greeted by caring citizens holding handmade signs of encouragement and support.

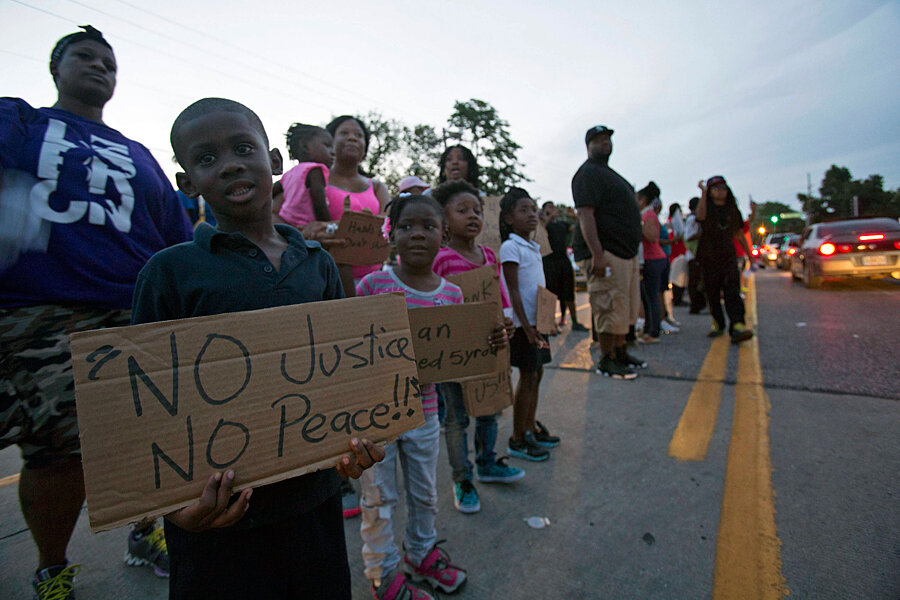

Amid the turmoil that’s unfolded in the wake of the fatal police shooting of Mike Brown, many people have been quietly uniting around concern for the community’s children – offering everything from food and school supplies to counseling for grief or trauma.

“I felt helpless – like there was sort of a cloud over our kids starting school ... and then I thought, whatever happened, we have to tell them you are safe here, you are loved, no matter what you look like or what part of the district you live in,” says Melissa Baird Fitzgerald, a local parent who set up a “Parents for Peace” Facebook page to encourage people to make and display the back-to-school signs.

“I wanted [the students] to feel hopeful and excited, and not to have to take on the burdens the adults are taking on,” she says. In just two days, nearly 600 people joined the effort – some sending in photos of their own family holding signs, from Chicago and beyond.

On Friday, Ferguson-Florissant teachers could meet with counselors, and 25 extra counselors and therapists will be on hand Monday to assess students’ needs, says district spokeswoman Jana Shortt.

The counselors are trained to deal with the effects of trauma, whether for a student who was directly affected by Mr. Brown’s death or for one seeing police in riot gear on the news and asking, Are we at war?, says Marie McGeehan, a spokeswoman for Great Circle, the group providing extra counselors.

“Our kids are going to tell us what they need,” Ms. Shortt says. “School is an ideal environment where children, together with trusted adults, trained adults, can have some productive conversations.”

Many students in the area have already been in school this week, at the Riverview Gardens School District, which includes the location where Brown was shot.

“Students have been noticeably upset at times,” says Riverview Gardens spokeswoman Melanie Powell-Robinson. Counselors are available for students, staff, and families, and extra security has been ensuring students’ safety this week.

“We’ve had no incidents,” Ms. Powell-Robinson says. “It’s a relief, but it’s also a testament to the fact that the community understands: These are our students.”

The students’ voices also contributed to what many have characterized as a hopeful shift in how the area is being policed. Before taking control, state highway patrol Capt. Ron Johnson spent about an hour with a group of Riverview Gardens high school seniors Thursday morning.

“It was important to me, because they decided this time to listen to the youth,” says Gregory Moore, one of the students who participated in the conversation. “I asked him, what could they do to make sure our rights were protected” when it comes to being able to protest freely without fear of tear gas or rubber bullets, Gregory says.

Brown’s death, and the police response to protesters, made Gregory “feel unsafe, because I have size and I’m quite large to be 17, and I can be seen as a threat when I’m not a threat.”

But he has come to school this week and says he’s been able to put it aside and focus on academics, “because I know what I want to do in life.” He’s planning to study in college to be an accountant.

Grief counselors will also be available to students as schools open Monday in the city of Normandy, where Brown had his graduation ceremony Aug. 1 after opting not to walk in the May ceremony, says spokeswoman Daphne Dorsey. (Brown spent his freshman year of high school in the Riverview Gardens district. He was reportedly set to begin college this past Monday.)

For children who missed free meals because school was delayed, and for families who couldn’t get groceries this week because of the disruptions, the need for food has become a key priority.

“Food pantries are getting bare,” says Pastor Joe Costephens of Passage Community Church in Florissant, which borders Ferguson. His church has worked with others to clean up the streets at night after demonstrations, and now they’re organizing a food and school-supplies drive.

By coincidence, Ferguson’s First Baptist Church had already planned a big community block party months ago for this Saturday afternoon. So food and supplies will be distributed to families there.

Hungry kids were also on the mind of Julianna Mendelsohn, a teacher in Raleigh, N.C., who heard about school being canceled for two days and realized a lot of Ferguson kids could be dependent on school meals for most of their daily nutrition.

On Wednesday night, she set up a Fundly.com fundraising site and spread the word on Twitter with #FeedtheStudents and #FeedFerguson, thinking she could raise a few hundred dollars. By early Friday afternoon, she was preparing to send just over $39,000 to the St. Louis Area Foodbank, which will coordinate the volunteers she attracted to help distribute the food to families in the Ferguson area.

“I'm blown away by how generosity and social media have created this,” Ms. Mendelsohn says. Events in Ferguson started because of a “polarized issue,” she says, “but anyone with half a heart would see the kids had nothing to do with this and need to be taken care of.”

Food, music, and activities will make for a celebratory atmosphere at the First Baptist Church Saturday afternoon. Ms. Fitzgerald will be there at a table, with art supplies people have donated, so that anyone can stop by and make back-to-school welcome signs as part of the Parents for Peace project.

“It’s a community effort, and we’ve needed that,” she says. “It’s a way to say we all have the same goals in mind and let’s just go forward.”