Age and politics: Americans test boundaries

Loading...

| Philadelphia

“You’ll live to be 90!” the voice rings out from the crowd. President Joe Biden laughs and makes the sign of the cross.

“I’ve been doing this longer than anybody,” the president told the crowd at a Labor Day rally in Philadelphia. “And guess what? I’m going to keep doing it, with your help.”

Why We Wrote This

Biden, McConnell, Feinstein, Trump: The number of top politicians in the United States who are of advanced age is leading to scrutiny over the role that age should play in political life.

Be it President Biden (age 80), former President Donald Trump (77), Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell (81), or Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein (90), the United States has never had so many top political figures of such advanced age.

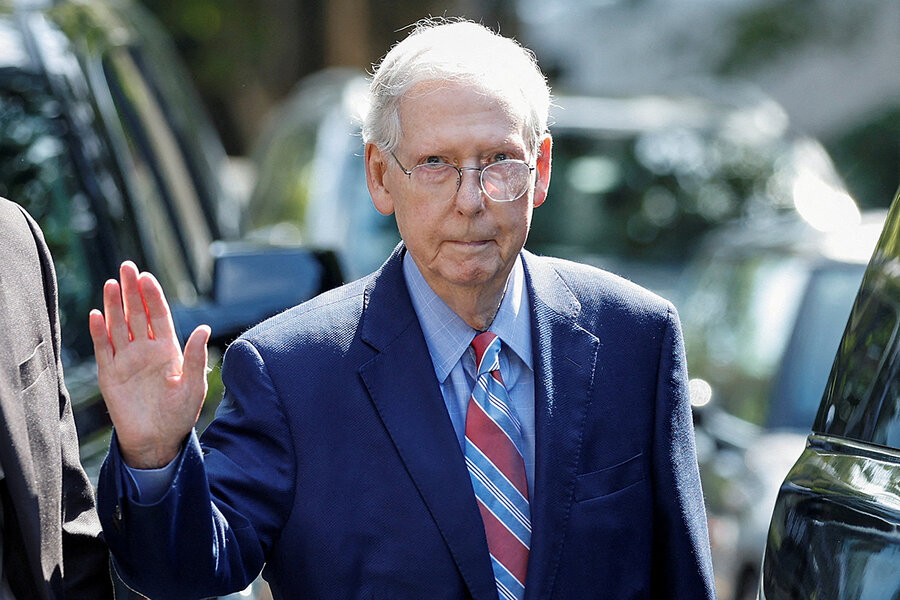

Senator McConnell’s latest health scare, in which he froze for more than 30 seconds while speaking to reporters last week – the second such public episode in about a month – renewed discussion of America’s “gerontocracy,” or “rule by elders.”

On Tuesday, the Capitol physician wrote in a letter to the Senate Republican leader that his examination and consultations with neurologists showed no sign of stroke or other disorders. Staffers attributed Mr. McConnell’s two recent health episodes to “lightheadedness” following a concussion after a fall in March.

All the nation’s “superagers” in high office suggest a modern-day reality: Those with certain occupations, income levels, and lifestyles can keep working well into their golden years. And in many top jobs, platoons of aides do a lot of the work. The downside is that public scrutiny has never been more acute, given the ubiquity of cameras and social media.

Today’s political leaders are “on the public stage at a time when they’ve never been more exposed to the world,” says Matthew Dallek, a political historian at George Washington University. “Any kind of frailty – real or perceived – is going to be exposed and magnified.”

“You’ll live to be 90!” the voice rings out from the crowd. President Joe Biden laughs and makes the sign of the cross.

“I’ve been doing this longer than anybody,” the president told the crowd at a Labor Day rally in Philadelphia. “And guess what? I’m going to keep doing it, with your help.”

It’s a pressing issue in American politics today: a leadership class dominated by people well beyond retirement age who, at least publicly, have no plans to step aside.

Why We Wrote This

Biden, McConnell, Feinstein, Trump: The number of top politicians in the United States who are of advanced age is leading to scrutiny over the role that age should play in political life.

Be it President Biden (age 80), former President Donald Trump (77), Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell (81), or Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein (90), the United States has never had so many top political figures of such advanced age – including, as of now, the likely major-party nominees for president in 2024.

Senator McConnell’s latest health scare, in which he froze for more than 30 seconds while speaking to reporters last week – the second such public episode in about a month – renewed discussion of America’s “gerontocracy,” or “rule by elders.”

On Tuesday, the Capitol physician wrote in a letter to the Senate Republican leader that his examination and consultations with neurologists showed no sign of stroke or other disorders. Staffers attributed Mr. McConnell’s two recent health episodes to “lightheadedness” following a concussion after a fall in March.

To the frustration of Democrats, the latest McConnell freeze-up generated new discussion of Mr. Biden’s age and whether he’s up to the rigors of another presidential campaign, let alone a second term.

All the nation’s “superagers” in high office suggest a modern-day reality: Those with certain occupations, income levels, and lifestyles can keep working well into their golden years. And in many top jobs, platoons of aides do a lot of the work. The downside is that public scrutiny has never been more acute, given the ubiquity of cameras and social media.

Today’s political leaders are “on the public stage at a time when they’ve never been more exposed to the world,” says Matthew Dallek, a political historian at George Washington University. “Any kind of frailty – real or perceived – is going to be exposed and magnified.”

Under the spotlight

The news Monday night that first lady Jill Biden had tested positive for COVID-19 again returned the health spotlight to Mr. Biden. But the president’s office reported within minutes that he had tested negative – and would keep testing regularly.

Mr. Biden is scheduled to go to India on Thursday for the G20 meeting of major global economies, followed by a visit to Vietnam. If the president has to cancel, that would send a signal of weakness, fairly or not, to the rest of the world.

Modern American presidents live a life of intense public scrutiny, and any vulnerability is hard to hide – regardless of age. The nation’s youngest elected president to date, John F. Kennedy, dealt with serious physical problems while in office, which only became known publicly after his assassination in 1963.

In the 1930s and ’40s, America’s longest-serving president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, worked hard to hide his health problems from voters – including his use of a wheelchair – and died soon after the start of his fourth term. Earlier, in 1919, President Woodrow Wilson was diagnosed with a severe stroke, and his administration hid the fact that his wife, Edith, played a crucial role in running his presidency until the end of his second term.

Today, 73% of Americans say Mr. Biden is too old to run for reelection, including two-thirds of Democrats, according to the latest Wall Street Journal poll. The same poll showed 47% of voters say Mr. Trump is too old to run. And when running head to head, the two are in a dead heat at 46% apiece. Polls also show consistently that most Americans don’t want a Biden-Trump rematch.

Political analysts see Mr. Biden as having slowed down physically in recent years, while Mr. Trump displays a more robust presence. But chronological age may not be the best way to present the Biden-versus-Trump matchup. Mr. Biden is a career politician, with long experience in government as a senator of 36 years and then eight years as vice president before reaching the Oval Office, while Mr. Trump represents a populist smashing of norms – regardless of age.

Mr. Trump’s one term as president reflected his status as a newcomer both to Washington and to governance. But after the January 2021 riot at the Capitol by Trump supporters who said the election had been stolen, the prospect of a Trump reelection suggests a more profound change to both the presidency and Washington.

Ultimately, experienced political hands see the age question as deeply embedded in old Washington ways. Until this past January, the top three Democratic House leaders were over age 80. Their decision to step aside reflected a stated goal of elevating the next generation. But the Senate, in particular, is known for having elderly members, some revered by voters for their historical significance rather than current mental acuity. The late Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, a decadeslong senator who served past turning 100, may be the most famous example.

Senator Feinstein, a Democrat from California, may be the best example today. A pioneer woman of the Senate, who served as mayor of San Francisco during a time of tumult, she is now a shadow of her former self. She has declined to resign, but has said she won’t run for reelection.

Last week, GOP presidential candidate Nikki Haley repeated the cliché that the Senate is “the most privileged nursing home in the country.” Ms. Haley has also proposed a “mental competency” test for politicians over 75.

Today, the average age of senators is 64, near an all-time high. But age isn’t necessarily an indicator of mental sharpness – both in the Senate and in the overall population. Sen. Bernie Sanders, an independent from Vermont, is almost 82 and may run for another term without raising an eyebrow. GOP Sen. Chuck Grassley is almost 90 and still commands respect as the senior senator from Iowa.

“The Senate has always been dominated by older senators – the so-called old bulls,” says Jim Manley, former spokesperson for the late Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid of Nevada. “What’s different today is Twitter [now known as X] and the 24/7 news cycle.”

Perks and a sense of service

Worth noting, too, is the distinction between politics and the corporate world. In government, elected leaders answer to voters – and must regularly face them at the ballot box. In the private sector, boards of directors and/or mandatory retirement ages can end a CEO’s tenure.

One problem, though, is that voters don’t always know when an official isn’t as sharp as they used to be. A voter might see a familiar name from their preferred party and stick with that brand, for better or worse.

For senior members of Congress, the perks of office – including a security detail, a big staff, and public prestige – can be hard to give up.

Longtime friends and acquaintances of Mr. Biden say there may well be a larger sense of purpose that is driving him to run for a second term, despite his advanced age.

“Based on observing him closely as a senator, in particular, for many years, I am confident that he believes he’s the only one that can beat Trump,” says Mr. Manley.

In an interview, former Sen. Chuck Hagel, a Republican from Nebraska, points to Mr. Biden’s lifestyle as important to his longevity and health.

“Joe never drank, never smoked, always worked out. He’s taking care of himself, always has,” says Mr. Hagel, who knew Mr. Biden well both in the Senate and when they served together in the Obama administration. “Yeah, he walks more deliberately, but so do I.”

Mr. Biden “brings steadiness and experience” to the presidency, “and with that, a certain amount of wisdom,” says Mr. Hagel, a former defense secretary. “The world is upside down – we’re all off balance, dangerously so. And if you get the wrong leadership, you could make some pretty stupid, severe mistakes that would cost not only the country but the world.”

Mr. Hagel also speaks highly of Mr. McConnell, whom he knows and likes, and expresses sympathy for his situation.

“That’s his life,” Mr. Hagel says of Mr. McConnell’s decades as a senator from Kentucky, including a record 16 years as the chamber’s GOP leader. “To consider stepping aside from a leadership position that he worked so hard to get – I know that’s a tough call, absolutely. It takes courage.”