Trump's steep learning curve

Loading...

| Washington

President Trump has learned plenty in his first 100 days in office. He has told us so.

Mr. Trump has learned that health-care reform and North Korea are complicated, that NATO and the Export-Import Bank are worth preserving after all, and that China, in fact, is not manipulating its currency. He’s also learned the enormous unilateral power American presidents enjoy as commander in chief – though he hasn't fully tested the limits of that power, or experienced the consequences of doing so.

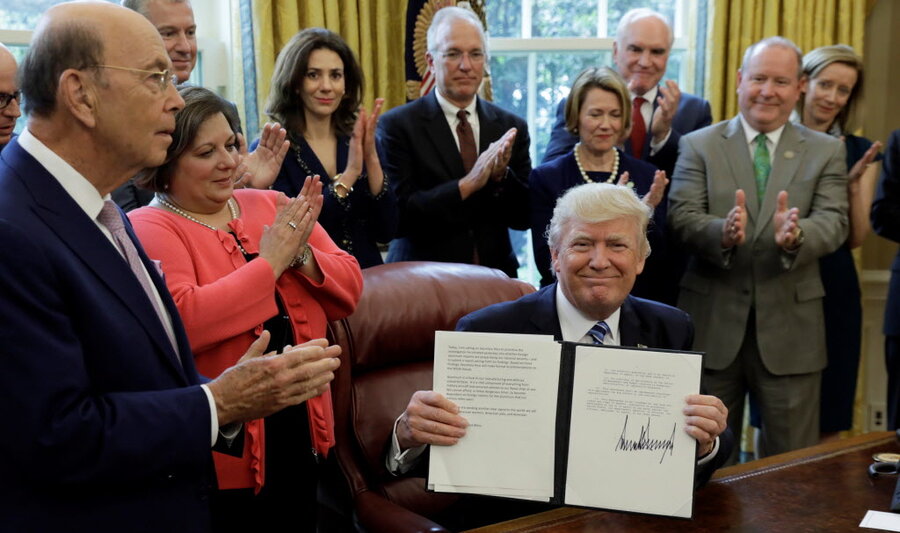

But the education of Donald Trump, 45th president of the United States, is about so much more than learning the vast array of issues that cross his desk in the Oval Office – and rethinking some positions along the way. It’s about discovering that running a business and being president of the United States are dramatically different enterprises. And that campaigning isn’t the same as governing, even as he does both simultaneously.

Still, if there’s one point about Trump that both supporters and critics agree on, it’s that he’s a listener. He’s not a reader or a details guy. “I’m an intuitive person,” he has said. As president, that intuition is informed by exposing himself to differing views, both among his famously clashing advisers, in his cable-news viewing, and in his dealings with Congress.

“I’ve had long discussions with the president in the Oval Office,” says Sen. Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah, who, as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, is a central player in enacting Trump’s agenda. “He listens.”

Trump is clearly learning something, says Dan Schnur, director of the Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics at the University of Southern California.

“The question is whether he’s learning enough things quickly enough,” says Mr. Schnur, who served as communications director for John McCain’s 2000 presidential campaign.

Beyond the froth of headlines, deeper truths

The firing of Michael Flynn as national security adviser and his replacement with H.R. McMaster represents progress in the latter’s “more conventional and less disruptive approach to security issues,” Schnur says. “The influence of people like [economic adviser] Gary Cohn demonstrates the same type of realization, that you can change Washington in some ways, but not in every way all at once.”

Indeed, some Trump skeptics on the Republican side have expressed relief that, over time, the president has amassed a team that includes respected figures from the world of national security and finance, and has declined to name some of the campaign gadflies (think Rudy Giuliani and Newt Gingrich) to formal positions in the administration.

For anti-Trump forces, the president’s loose, unorthodox style has made him hard to counter, especially amid the daily barrage of tweets and pivots. One day he’s ready to terminate NAFTA – the agreement that governs the $3.5 billion in daily trade among the US, Mexico, and Canada – and the next, he’s dialing back to a less-disruptive “renegotiation.”

But beneath the froth of daily news coverage, there are deeper truths that have dominated Trump’s first 100 days in office: Foremost is the grand political science experiment of having a political novice in the Oval Office, surrounded by an inner circle of advisers who are also new to governing. It has been a bungee jump for everyone – Congress, the political parties, world leaders, and the American people.

Also central is Trump’s decision to start campaigning for reelection essentially from Day One of his presidency. Trump filed for the 2020 election on Inauguration Day of 2017, a move he says was not a “formal announcement of candidacy,” but he has in fact been holding campaign events. His rally in Harrisburg, Pa., on Saturday night – counter-programming to the annual White House Correspondents’ Association dinner – is being organized by Donald J. Trump for President, Inc, not the White House.

All presidential actions have a political dimension, but Trump’s manifestation of that is unique.

“He is the first president in our history who did not believe that it was necessary to expand his base of support in order to succeed,” says Schnur. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m sure he’d rather be more popular than he is, but I suspect Trump believes he probably couldn’t unify the country even if he wanted to.”

Consider the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll. Trump is the least popular president in modern history at this stage in office, at 42 percent job approval, and yet 96 percent of those who say they voted for him last November say they’d vote for him again today. The poll also indicates the possibility that Trump could win the popular vote – which he did not get last November – if a rerun of the 2016 election were held today. For those tired of the intense polarization gripping Washington, these results do not bode well.

Why it's hard for CEOs to run democracies

Another unique dimension of the Trump presidency is his background in business. There’s a longstanding trope that a businessman could do better in governing the country than a career politician, and Trump, in theory, provides an opportunity to test that proposition.

The test has only begun, but Gautam Mukunda, a professor at Harvard Business School, offers some early caveats.

“No doubt there is some overlap in the skills required to be president and the skills it takes to be a really good CEO,” Mr. Mukunda says. “Large organizations, even businesses and government ones, do have some commonalities.”

But there’s a fundamental difference between a business and a government. “From the very simplest thing, most corporate CEOs have a power and control over their organization that’s a lot more akin to an absolute dictator than it is to the president of the United States,” he says.

The goal of a business is to make a profit, whereas the goals of government are much more contentious, he adds. “Should the United States government guarantee health insurance to all American citizens or not? That is a matter of great debate. The question of how we should do that is secondary to the question of if we should do that.”

Then there’s Trump himself – and his particular way of doing business. Trump is known for being litigious, and for constantly trying to get a better deal, even after a deal has been signed. When a deal falls apart, he can move on to another deal, with another set of people.

“His entire career he has played in a series of one-shot games,” says Mukunda. As president, “he’s still handling every interaction like they’re one-shot interactions. So he can get into a fight with the prime minister of Australia… but he can’t go elsewhere for a better deal. Australia’s not going away.”

Ever the performer

Author Gwenda Blair has interviewed and interacted with Trump many times in her work on a biography of the businessman and reality TV performer, long before he announced for president.

Today, nothing about Trump’s presidency surprises her.

“It really is the same MO that we saw in his career up until the campaign, then throughout the whole campaign,” says Ms. Blair. “He’s a performer: Always keep people distracted, keep changing the subject. Really, he has spent 40 years honing his ability to keep all the attention on him, and it still works.”

Blair calls him the framer-in-chief. “He keeps framing what success means,” she says. “He ran on the idea that he would have the most successful first 100 days ever.”

Every new president makes mistakes, and goes through a learning curve. Trump’s first 100 days have been tougher than the norm, however. Trump failed on his first pass at health-care reform, and executive orders targeting illegal immigrants are stuck in court. But in his press releases and public statements, he’s projecting an image of success.

“Undergirding everything, really, is the ongoing delegitimization of traditional news, of the primacy of facts, the importance of accuracy in replacing that with a kind of ever-shifting narrative that accepts contradictions, zig-zags, 180-degree pivots,” Blair says. “And on all of those things, there is no fixed point except him.”

The experiment has only just begun.

Staff writer Francine Kiefer contributed reporting.