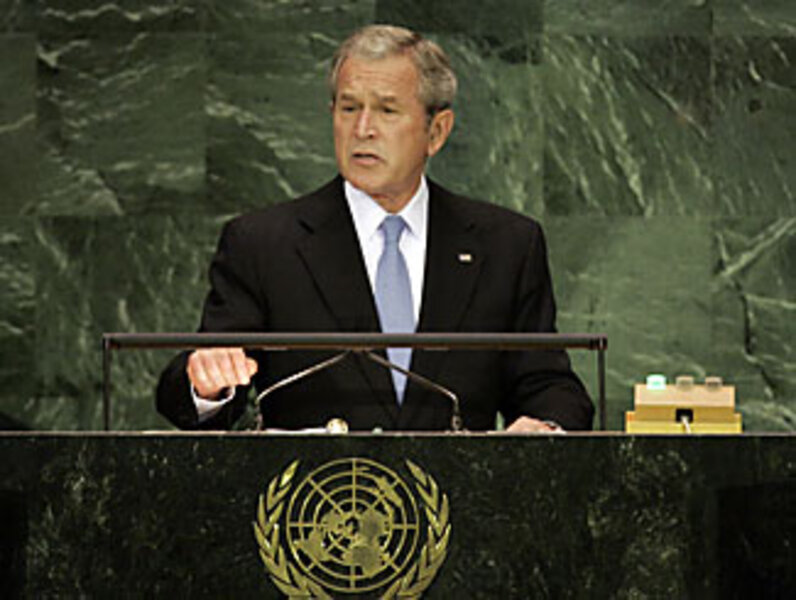

Bush and the U.N.: a reluctant embrace

Loading...

| United Nations, N.Y.

When President Bush stands at the podium of the United Nations General Assembly Tuesday morning, his last speech as American president to the global forum will mark the administration's trajectory from disdain and disregard for the UN to pragmatic acceptance and even, according to some US officials, whole-hearted engagement.

That shift has come in part because the United Nations has proved to Mr. Bush to be an essential partner in his central national security focus – the battle against terrorism. The body Bush once said risked "irrelevance" has taken a number of actions since 9/11 – targeting the finances of terrorist groups, enacting controls on the spread of weapons of mass destruction, approving sanctions to halt nuclear proliferation – that reinforce US national security goals.

The UN "looks very different today than it did on Sept. 10 of 2001, and those changes put the UN on better footing to prevent future terrorist attacks," says Brian Hook, acting assistant secretary of State for international organization affairs. Noting that the UN's charter calls for it to address threats to the world's peace and security, Mr. Hook says, "This president has worked very hard to help the UN give meaning to its ideals."

Bush's evolution from skepticism and antagonism toward the UN to embracing it is reminiscent of the path taken by another US president, Ronald Reagan. President Reagan was another two-term president who initially had little use for the unwieldy international body but left the White House with a better appreciation for the world body, UN scholars say.

As a budding conservative leader, Reagan wrote of the folly of "subordinating American interests" to the United Nations, and, through most of his presidency, dismissed the UN as a den of authoritarian regimes and small despots. But he sang a different tune by the time he addressed the General Assembly for the last time in September 1988. Saying he "stood at this podium … at a moment of hope," Reagan reviewed freedom's advance over the previous eight years, lauded UN reforms, and cited specific issues such as terrorist hijackings where the UN had played a crucial role.

"Yes, the United Nations is a better place than it was eight years ago," Reagan said, "and so, too, is the world."

Parallels with Reagan

Bush's speech may strike a similarly conciliatory and hopeful tone, given the two presidents' parallel tracks. "Reagan ended his tenure with one of the warmest speeches to the UN I can ever recall hearing," says Edward Luck, senior vice president of the International Peace Institute (IPI) in New York with long experience at the UN. "He really treated the UN as if he were coming home for the last time."

Mr. Luck, who says he has "never seen an administration so engaged in getting things done though the Security Council as the Bush administration in recent years," believes Bush is likely to offer an inventory, as Reagan did, of areas in which the US both challenged and worked with the UN.

The image of Bush as antagonistic toward the UN was sealed with his belittlement and marginalization of the world body over its failure to support the US invasion of Iraq. The bad blood continued to flow as the UN confronted the oil-for-food scandal and as the Bush administration, led by former ambassador John Bolton, pushed an all-or-nothing approach to UN reform in 2005.

But the Bush administration's approach began to evolve markedly in the second term. The administration sought international assistance on security issues like terrorism and nuclear proliferation as well as on "soft power" issues, from the stabilization of Iraq to reduction of poverty and disease in Africa.

"When you look at the president's record of engagement with the UN, you discover we have pursued a robust multilateral approach to solving a lot of the problems we face," says Hook. This is true not only of issues of national security, he says, but also in battling HIV/AIDS, in humanitarian issues, and in human rights.

A change of heart or circumstance?

But others see little real change in Bush's estimation of the UN and of multilateral diplomacy in general. Rather than any change of heart, what these critics see is a reluctant recourse to the UN when Iraq did not unfold as the administration had planned.

"The same Bush who in 2002 was really contemptuous of the UN for its inability to enforce its own sanctions and resolutions on Iraq came back for help with the occupation," says Michael Doyle, a former US official at the UN and now a professor of international affairs at Columbia University in New York."It's an evolution born of necessity."

More striking than Bush's resemblance to Reagan is his difference from his own father, Mr. Doyle says, noting that as a former US ambassador to the UN, the first President Bush knew and valued the organization.

"Bush Senior had proven his esteem for the UN and the principles it stands on by fighting the Gulf War with a coalition he put together within the framework of international law and with Security Council approval," Doyle says. "Then he came in [in his 1988 speech] and offered a number of specific proposals to build up the capacity of the institution so it could be better prepared to assist in future security crises," he adds. "It was a remarkable act of statesmanship."

In his speech, the elder Bush – in the middle of a reelection campaign he would ultimately lose – offered specific steps for enhancing the UN's peacekeeping function. He announced plans to make peacekeeping a permanent part of US military school curriculum and offered the use of US military facilities for training multinational forces.

The younger Bush may not offer such specific proposals. Given lingering resentment among the UN's 192 members towards the US, a more philosophical take on America's relations with the UN might be more productive, says IPI's Luck.

"It's been a long time since the US dominated the organization, but the concerns that it does are still very strong," he says. "Bush would be doing his successor a favor by paving the way with something more reflective on the UN and the American relationship with it."