Unarmed black granddad killed by cop, in shades of Ferguson

Loading...

| Atlanta

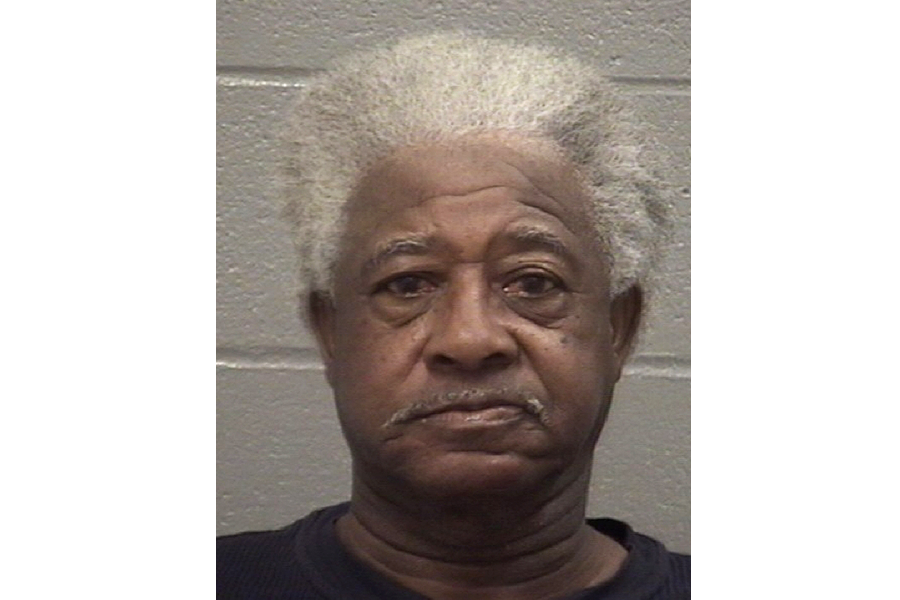

The case of an unarmed black grandfather shot to death in his own driveway by a white police officer in South Carolina has fueled demands for more transparency into cases where unarmed civilians are killed by police.

Police have confirmed that North Augusta Officer Justin Craven shot and killed Ernest Satterwhite in February, but have refused to release details about their investigation.

The lack of transparency into Mr. Satterwhite’s death and Mr. Craven’s culpability has raised hackles in the black community.

Such tensions have intensified since the Aug. 9 police shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., where unrest still simmers as residents demand the arrest of the officer.

The two incidents cut to a stark fact of US policing: Namely, that a real and sometimes perceived lack of transparency from police fuels distrust – which in turn raises the stakes for officers on the beat.

Indeed, given a recent increase in officers dying in ambush attacks, “I’m afraid it might become a default response for officers to have their guns drawn and maybe react a little more quickly,” says Thomas Aveni, a veteran police officer and executive director of the Police Policy Studies Council in Spofford, N.H.

The handling of the incident involving Craven stands in stark contrast to another case in the state from earlier this month. South Carolina Highway Patrol decided to release video last week that shows state Trooper Sean Groubert, who is white, telling a black motorist to get his license and then shooting him when the motorist reaches into his own car. The trooper was fired and brought up on felony assault charges.

US police shoot and kill an average of 1,000 people a year, 1 in 4 of whom are unarmed, according to data from Mr. Aveni and the FiveThirtyEight blog by Nate Silver. Seventy-nine officers have died so far this year, 35 from gunshots, according to a nonprofit group called the Officer Down Memorial Page.

Detailed information about police shootings is often scant. It’s also exceedingly rare for a police officer to be charged in such a shooting, largely because the US Supreme Court has said officers must be judged by whether their use of force is "objectively reasonable" in the full context of events. And many police departments are hesitant to release piecemeal information because it might taint a jury pool.

It’s also worth noting that grand jury proceedings, in which charges are considered, are characteristically closed-door events.

“[I]t is impossible to easily tell in any given situation, whether the officer was found at fault, whether race or mental health issues were factors, whether the shooting was avoidable or whether innocent bystanders were struck by gunfire,” writes John Monk of The State newspaper in Columbia, S.C.

In the Craven case, prosecutors and police have refused to provide documents requested by the Associated Press and answer questions from the news organization about the details of their investigation. According to AP, prosecutors sought a voluntary manslaughter felony charge against the officer. But a grand jury instead indicted him last month for "using excessive force and failing to follow and use proper procedures" – a misdemeanor.

Craven is now on paid administrative leave from the force.

After Satterwhite pulled into his own driveway at the end of a nine-mile slow-speed chase, witnesses said Craven rushed toward Satterwhite’s car and shot him twice in the chest after he claimed Satterwhite reached for his gun. Satterwhite had a history of refusing to stop for police, but police had no record that Satterwhite had ever been violent.

Black leaders in South Carolina are among those demanding faster and more complete release of information from police. “If there’s nothing to hide, what’s the big deal?” state Rep. Joe Neal (D), who is black, told The State.

“Openness can help," agrees Aveni. But he adds, “What police are concerned about is looking dishonest if they step forward too soon” with information that’s not fully vetted.