Who 'likes' Mitch McConnell? Facebook unveils new tool for election 2014.

Loading...

| Washington

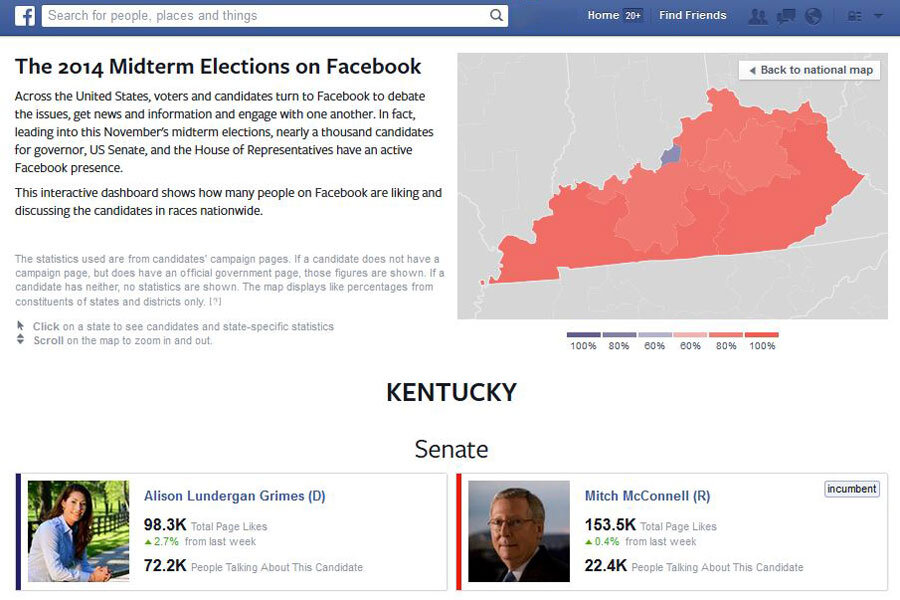

In the closely watched Senate race in Kentucky, Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell is clobbering Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes with affection – he’s got 153,500 “likes” on his Facebook page vs. her 98,300 likes.

Does that mean he’ll win?

This week, Facebook introduced an interactive map of House, Senate, and governor races that shows how many people “like” those candidates and are talking about them.

You can click on the map and find, for instance, that while Senator McConnell may be winning the horse race in “likes,” he’s lost in the dust of buzz about his competitor. Roughly three times more people are talking about Ms. Grimes, based on Facebook comments and “shares” of content.

Facebook cautions that its new election tracking tool can’t predict winners or losers, though some outside experts think it has predictive potential.

The downside is that campaigns can gin up their Facebook numbers by suggesting likes from friends or introducing content on users’ news feeds that look legitimate but are really ads. They can also sabotage their opponents’ sites with negative comments.

And unlike a poll of registered voters, Facebook isn’t asking whether a user is likely to vote and for whom.

What the Facebook map does show is how engaged campaigns are with the public on one of the giant social media platforms. And it is giant. The company told Politico that in the past three months, 22 million Facebook users in the United States had 150 million interactions about the coming midterm elections.

The “real value” of Facebook as an election tracker is its size and demographics, says Edward Erikson of the strategic communications firm MacWillaims Sanders Erikson. “Facebook has a key demographic that aligns with the people most likely to vote, people aged 35 to 65.”

Unlike the interactive map, which reflects just raw data, Mr. Erikson’s company is using Facebook’s numbers to see whether it can forecast election outcomes. In 2012, Erikson and his colleagues used the data to correctly call eight out of nine tossup Senate races.

They calculated the growth in the number of fans (likes) and the growth in engagement, and then figured out the relationship between the two – how many fans were engaging – in order to see how well a candidate was actually mobilizing supporters.

This year, Erikson’s company is again working with Facebook data to forecast Senate outcomes, accounting for factors like incumbency. They’re posting their results on their website, hashtagdemocracy.com. Except for a few races, such as Alaska and Minnesota, they appear to be on par with polling.

Erikson suspects that Facebook’s real intent is to use its data as a revenue generator with campaigns. In 2012, campaigns spent 12 percent of their communications budgets on social media.

“In the future, Facebook could tell us not only who is interacting with what candidate but what registered voter is interacting with that candidate,” Erikson says. Facebook is trying to convince candidates they need their tool and they need to spend ad dollars.

“They’re saying, ‘You need to pay attention to us. You’re in a race not just for votes but for numbers of fans.’ They are trying to create a new horse race.”