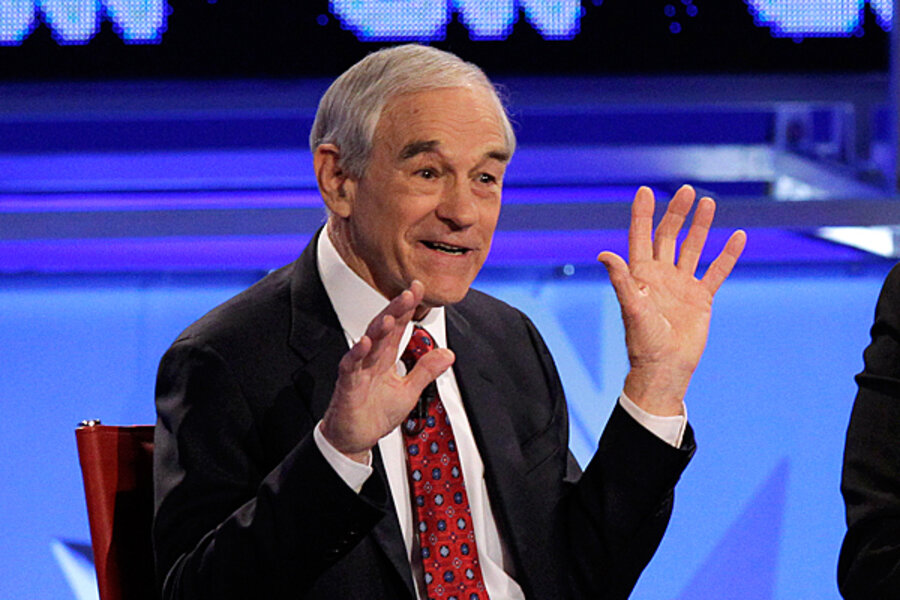

Overview. The Texas congressman, known for his libertarian views, proposes the most sweeping government downsizing of any of the Republican candidates. His philosophy is to cut taxes, transfer more power to the states, and give more choice to individuals. His plans would do the most to control the national debt, the CRFB finds, but they still might not leave the debt substantially smaller than it is today.

The results. National debt would stand at 67 percent of GDP by 2021 under the "low-debt scenario" for Representative Paul's economic plan. Economists would see such an outcome as a meaningful improvement in America's fiscal condition, compared with current trends. But that doesn't mean they would endorse Paul's chosen mix of tax and spending policies.

In the "intermediate-debt scenario," which the CRFB views as its more realistic assessment, national debt would rise to 76 percent of GDP by 2021.

Why his plan gets there. Paul's reductions to federal revenue would span from personal to corporate income taxes (and include eliminating the estate tax). But under the two scenarios shown here, his spending cuts would be even larger. That would steer deficits downward compared with their trend.

He would parallel other GOP candidates by block-granting Medicaid and some other entitlement programs to the states, as well as freezing their growth. He also calls for big cuts in both defense and nondefense spending.

One wild card, with Paul, is his proposal to end the Federal Reserve. He has acknowledged that, if elected, he would be unlikely to achieve this goal quickly. He argues that his proposed changes to monetary policy would curb inflation and strengthen the economy. Some economists say the absence of a central bank could destabilize the economy, with negative implications not just for jobs but also for federal deficits.