White nationalist event at Texas A&M reignites campus discourse debate

Loading...

Hundreds of students at Texas A&M University protested white nationalist rhetoric delivered on their campus Tuesday night, reigniting a debate about political discourse at colleges and the rise of fringe political movements following the election of Donald Trump.

Richard Spencer is a member of the so-called alt-right white nationalist movement and the president of the National Policy Institute, a self-described "organization dedicated to the heritage, identity, and future of people of European descent in the United States, and around the world." He made headlines last month when he addressed white supremacists at a gathering in Washington D.C., with the words, “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!”

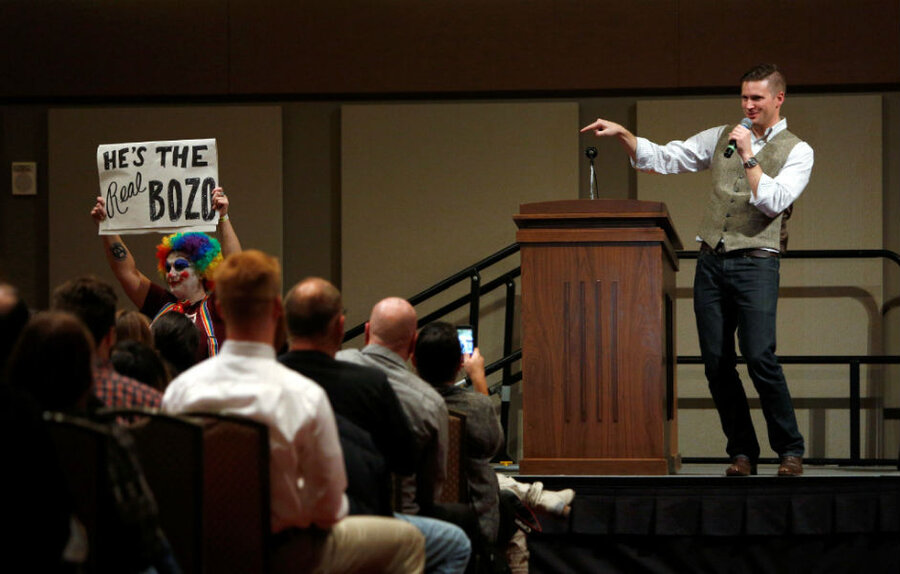

Mr. Spencer arrived at the College Station campus Tuesday and spoke to a crowd of around 400 people for roughly two hours, delivering a speech steeped in white supremacist ideals and advocacy. A "handful" of people appeared to support his ideas, while most seemed to be protesting his presence, according to the Texas Tribune, which reported that hundreds more demonstrated outside.

"We won and we got to define what America means," Spencer said, according to the Tribune. "America, at the end of the day, belongs to the white men."

Ideas and opinions on campuses across the nation continue to clash following the election, with many students overtly promoting tolerance and denouncing extreme views that demean others based on race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. But some criticize protestors who object not only to a speaker's ideas, but also their presence on campus, accusing Millennials of using "political correctness" to censor controversial viewpoints and robbing themselves and others of a robust education based in political discourse.

And after Mr. Trump’s unexpected presidential victory, the idea of suppressing controversial views and ignoring swathes of the nation whose views some deem “deplorable” has come under additional fire. Excluding such viewpoints, many say, has not rid society of them, but alienated those who hold them, allowing anger and hatred to brew beneath the surface.

“[Universities] are so uniformly liberal and leftist, it causes a distortion in these kind of debates about what’s thought of as mainstream and affects academic research. Questions don’t arise that would otherwise arise,” says Bradley Campbell, a professor of sociology at California State University, Los Angeles, who studies moral conflict, in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

Typically, however, students are protesting controversial speakers with less radical ideas. Spencer is a more extreme case, Dr. Campbell says, one who likely doesn’t contribute to insightful debate or a balanced education.

“I wouldn’t think that it’s a good idea for any campus group to invite him,” he adds. “His is a fringe view. I don’t see much benefit from having him or that kind of extreme because it’s not really part of the political debate in this country. Excluding ideas that are is a problem.”

Still, students are pushing back on less controversial speech, aiming for a future that is more inclusive to minorities and free of hateful comments. Among voters between the ages of 18 and 29, Trump only garnered 37 percent of ballots cast, and many have staged protests across the nation that criticize his rhetoric, cabinet appointees, and policies.

A similar scene played out last week at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., where former right-wing Breitbart news executive Steve Bannon was scheduled to speak as part of Trump's transition team. While Harvard didn’t give into threats of student protests, Mr. Bannon canceled the appearance himself, citing a conflicting schedule.

Texas A&M did not invite Spencer to speak at the university and publicly opposed the event. But as the school is a public university, it could not reject him. Instead, it was Preston Wiginton, a former student at the school who still resides in College Station, who invited Spencer to the campus and reserved the space for him to speak.

"I think (the United States) was at one time (a white nation)," Mr. Wiginton told CNN. "I think the reaction to Trump being elected, and the reaction with the alt-right being popular, is a reaction to it declining as a white nation."

Wiginton, who said he doesn’t like to identify himself with political labels, says that he’s sympathetic to the movement’s views, and thought Spencer could bring some "valid points" to the university.

"Why would I want to see America become less white?" Wiginton said. "Why would I want to be displaced and marginalized? Only people with a mental illness want to be displaced."

Though no longer a student at A&M, Wiginton has frequently hosted controversial figures at campus events, including a 2015 lecture titled “American Liberalism Must Be Destroyed” by Alexander Dugin, a far-right-wing political scientist with ties to the Russian government, the Texas Tribune reports. Most of those events drew little attention. The arrival of Spencer, however, was another matter.

Tensions on at Texas A&M ran high in the days before his arrival, and on Tuesday, students poured onto campus and in the auditorium in droves, wielding signs that read “My heritage does not hate,” and “Tolerance of intolerance is cowardice.”

Although other groups may not extend invitations to Spencer or speakers with aligning views, the type of reactions seen at Texas A&M Tuesday and Harvard last week are likely to accompany other extremely conservative visitors, as well. The sparring opinions on campus mirror a fight between dignity culture, which downplays the importance of insults and offenses, and victimhood culture, which expresses more sensitivity to slights and offenses, arguing that they have an impact to shape the world for many, Campbell says.

“Victimhood culture blurs the distinction between speech and violence, when you’re actually talking about things that are words and characterizing these things as akin to violence,” Campbell says. “There’s that reaction – that people shouldn’t be allowed on these campuses if people express these kind of views, and that it harms the safety of the students.”

Despite pushback from many who say universities are coddling students by providing safe spaces and circumventing topics or words that are "triggers," students continue working to maintain inclusive, non-offensive cultures on their campuses – with or without protests.

Hundreds of A&M students and local residents gathered at an "Aggies United" event on campus, intentionally scheduled to coincide with Spencer's talk, where organizers hoped to counter his message with one of community.

"It was obviously an intentional effort to give people that wanted to do something an option of doing something positive," Kathy Hansen, a nearby resident, told the school paper. "We're not yelling, we’re not protesting, we're not holding signs. We're in unity; we're choosing something different. We are making a statement."