Next fracking controversy: In the Midwest, a storm brews over 'frac sand'

Loading...

| Arcadia, Wis.

Kyle Slaby bounds up the slope behind his house, stopping at the sandstone outcrop he hopes will save his family's farm. The Slabys grow corn and soybeans on the ridgeline above. But these days there's more money – a lot more – in mining the sand below.

"A lot of people look on it as an extension of farming," Mr. Slaby says. "It's another crop you're harvesting."

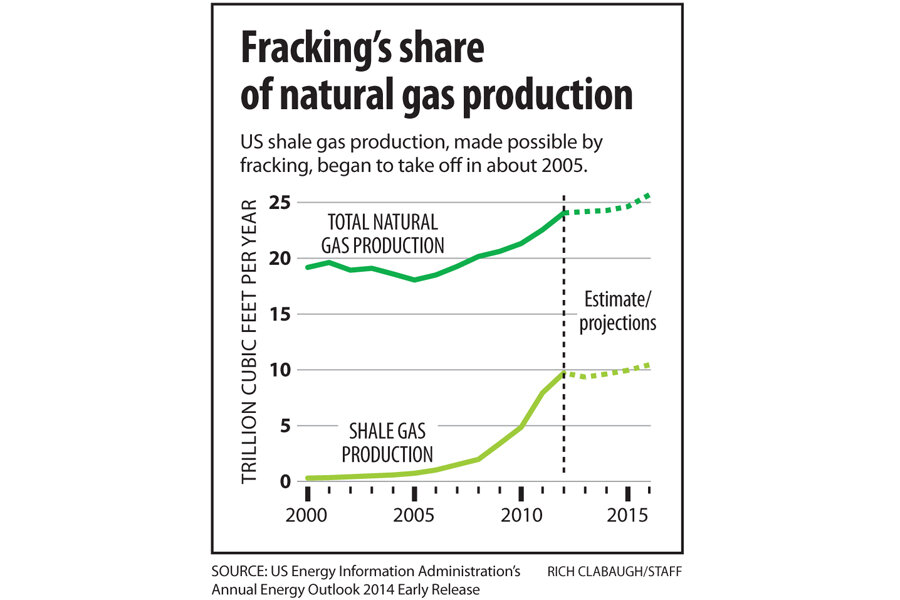

Sand has become a valuable – and deeply divisive – commodity in the upper Midwest. Hydraulic fracturing, a method of extraction also known as fracking that has boosted oil and natural gas production across the United States, requires sand, and there's plenty of it here. And so in dozens of small towns and rural townships in Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa and especially Wisconsin, the demand for frac sand, as it's called, has brought a surge of new mining activity. Scores of companies have poured in, eager to take advantage of the thick sandstone that underlies the bluffs and ridges of the region's picturesque river country.

The sand rush has created jobs and enriched landowners, but it also has divided neighbors, strained local governments, and set off fierce debates over its benefits and its costs to the land, public health, and quality of life.

"I don't think we were surprised that they found ways to extract it," says John Kimmel, the mayor of Arcadia, a town of 3,000 residents in Wisconsin's Trempealeau County. "I think we were surprised at the effect it's had on the community – and on how many mines have just started to pop up all over."

Indeed, where State Trunk Highway 95 winds among the farms and hills just east of Arcadia, new mines stand out as gashes of raw earth and yellow stone. Pyramids of sand await transport to distant drilling fields. Joe and Cindy Slaby and their son Kyle, who farm just north of the highway, have proposed mining their sand, too. "It's some of the best in Trempealeau County," Ms. Slaby says.

Others are less cheerful. The mining boom has alarmed many residents who worry that it will pollute the air, harm local water supplies, and, in places like Arcadia, mar the rural loveliness that has given the town its name.

"We have a beautiful land here, and they are going to destroy it," says Patricia Kamla, who is in her late 70s and lives near a mine on the outskirts of Arcadia.

In December, concerns like these seemed at least partly vindicated when Wisconsin's attorney general announced a $200,000 fine against a Pennsylvania company for repeated violations of air and storm-water regulations at a mine in Blair, a town 12 miles east of Arcadia. (The company, Preferred Sands of Radnor, Pa., says it's fixed the problems.) Since 2012, Wisconsin has found nearly two dozen sand-mining operations in violation of air and water pollution rules.

Residents complain that the mining boom has overwhelmed the state agencies responsible for monitoring it. It also has sorely tested local officials, few of whom knew anything about sand mining until it came. And it's become politically contentious. Many communities have tried to use their zoning and police powers to limit where, when, and how mines can operate. But Wisconsin Republicans, who are trying to make the state friendlier to business, want to curb those powers.

Rich Budinger, president of the Wisconsin Industrial Sand Association, a trade and lobbying group, says companies need regulatory consistency and freedom from rules he says are aimed at keeping them out. But many communities oppose statewide legislation that would curb local regulatory powers, and at a hearing in Madison, Wis., March 3, Republicans were on the defensive.

Sand mining goes back more than a century in the Midwest, with most of the sand used in metal casting, glass manufacturing, and construction. But about four years ago, as fracking began to yield large quantities of natural gas from shale formations in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, interest in Midwestern sand soared.

"It's some of the best in the world," says Mark Riley, an executive with AllEnergy Silica, a company in Johnston, Iowa, that wants to open a mine near Arcadia.

What makes it so special? Frac sand consists of fine particles of quartz whose sharp edges have been worn smooth over time. The sand exposed in the hill country on both sides of the Mississippi River is more than half a billion years old. To extract it, mining companies scrape away the soil, break up the sandstone with explosives, and then crush it. The raw sand is washed, sorted by size, and shipped by truck, rail, and barge to fracking operations in the US and Canada. There the sand is mixed with water and chemicals and pumped underground, where the particles lodge in cracks and prop them open while gas or oil flows out.

Government and industry experts estimate the US production of frac sand at 25 million to 30 million metric tons a year and growing – most of it now coming from the upper Midwest.

The mining boom looks different from state to state. Minnesota and Illinois each have a handful of large frac sand mines, with new ones on the way. Iowa has ample sandstone, but so far only one operating mine. Wisconsin, however, with its easy access to railroads and relatively permissive regulations, has become a hive of sand mining. In 2010, the state had 10 mines and processing facilities. Today it has 132, with nearly 100 more that are in the planning stages or have been approved.

"There are so many, it's hard to keep track of them," says Thomas Dolley, a sand expert with the US Geological Survey outside Washington.

The mining boom has aroused opposition, spawning numerous small activist groups with names like Preserve Trempealeau County and Save the Bluffs. Some residents of sand-rich areas in Iowa, Illinois, and Minnesota – about 225 of whom met at a "Citizens' Frac Sand Summit" in Winona, Minn., in January – are alarmed by what they see in Wisconsin. "We don't want to be like them," says Amy Nelson, an anti-mining activist from Goodhue County, Minn. "We don't want to be overrun by sand mines."

In response to concerns like these, Minnesota's Democratic-controlled Legislature last year instructed state agencies to develop stricter standards for sand mining and to offer local governments technical assistance in permitting and regulating the industry.

For some communities, sand mining is becoming all-consuming, with public meetings attracting packed audiences. It also has raised ethical concerns, with some elected officials who own land becoming involved in local mining projects. And it has opened a door between government and industry, as mining companies hire workers from the local departments that regulate them. Kevin Lien, head of Trempealeau County's Department of Land Management, says he has turned down five job offers.

Mining's proponents argue that the industry is helping communities by creating jobs and increasing the local tax base. Mr. Budinger says sand mining has created "thousands of jobs" in Wisconsin, including at the mines and in support services like trucking.

In addition, many rural Midwesterners – including Tom Bice, a Trempealeau County supervisor – believe that landowners ought to be free to do what they wish with their land.

"I'm an advocate of people's right to do what they choose to do, if it's legal according to state statutes and rules," he says.

Critics say the benefits of sand mining flow mainly to distant, large mining companies. The new mining has generated relatively little local economic activity and "not as many new jobs as they want us to think," says Patricia Malone, an economic development official with the University of Wisconsin-Extension. Local officials worry about damage to roads from 18-wheelers hauling heavy loads of sand.

People who live near mines complain that the activity has brought blasting, bright lights, and the growl and beep of heavy equipment to otherwise peaceful agricultural valleys.

"I think there are areas where this could be suitable and could coexist with neighbors and existing land use," says Paul Winey, a physician's assistant who lives in the thick of mining country outside Arcadia. "But there are also areas where many of these mines have been permitted where it's not a good fit.... A lot of folks have chosen to move out to live in the country for peace and solitude, and to have what could be a 24-hours-a-day operation with noise and increased traffic and the potential for health problems move next to them, it's not what they bargained for."

A big question about sand mining is the risk to public health from dust. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), prolonged exposure to airborne crystalline silica – tiny particles of sand – can cause silicosis and increase the risk of lung cancer. It's not known exactly how much crystalline silica sand mining puts into the local air, in part because of the difficulty and expense of measuring it. But many residents are worried.

Crispin Pierce, director of the Environmental Public Health program at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, says his preliminary testing outside 15 mines and processing plants in western Wisconsin revealed levels of fine dust that exceeded standards set by the US Environmental Protection Agency. Some of this dust was probably crystalline silica. Testing by the US Mine Safety and Health Administration found that, on average, crystalline silica makes up 14.5 percent of the dust at Wisconsin sand-mining operations.

But concerns about dust extend far beyond the Midwest to where frac sand is used. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health issued a "Hazard Alert" after a study of 11 fracking sites in five states found levels of crystalline silica that consistently exceeded occupational health standards, sometimes by as much as 10 times. In September, OSHA proposed cutting in half the permissible levels of exposure to crystalline silica at work sites.

Minnesota recently began testing for crystalline silica and other fine particles at mines and along a busy haul route. It is also rewriting air-quality standards for sand mining. Wisconsin has declined to undertake similar testing or to develop its own air-quality rules. State officials argue that a combination of existing air monitoring, national air-quality standards, and requirements to contain dust by technological means is adequate to protect public health.

Budinger, whose group represents some of the largest sand-mining companies in the Midwest, insists that the activity is safe. "If you are following the regulations, there is no threat to the environment, no threat to public health," he says. Yet he concedes that, with the flood of new companies, some may not be following the rules. "It's an enforcement problem," he says. "These companies need to be held accountable."

Few places have seen more mining activity than Wisconsin's Trempealeau County, which residents call the "ground zero" of sand mining. In four years, county officials have approved 28 mines and processing or shipping facilities. They have turned down one.

But in August, bowing to local concerns, county officials imposed a one-year moratorium on new applications to give them time to assess mining's risk to public health. Other local governments have used moratoriums to slow the sand rush while they update regulations.

Still, local efforts to regulate sand mining have sometimes misfired. Until recently, Trempealeau County limited mining operations to the hours of 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. on weekdays, with shorter hours on Saturdays and none on Sundays. Companies circumvented these rules by having their mines annexed to nearby municipalities not subject to county regulations. It's a common tactic. Faced with the prospect of losing all control over sand mining, Trempealeau County in December decided to allow the processing of sand through the night.

The Arcadia Sand mine is one of the new mines. It employs about two dozen workers to mine and process the sand, and with 231 acres, it could operate for as long as 30 years.

It's been controversial almost from the start. In April 2012, its owners had the mine annexed to Arcadia, which enabled it to operate around the clock. Until recently, Bobbi and Richard Halvorson lived with three of their children in a rented house about a quarter mile from the mine. The valley was peaceful, they say – until the mine started up. After that, Ms. Halvorson says, dust dirtied the laundry she hung out to dry. Her daughter's asthma worsened. And heavy equipment kept them awake at night. "It was so loud it would wake me from a dead sleep," she says.

The last straw came when blasting knocked Mr. Halvorson's stuffed deer head from the wall. The Halvorsons finally moved last summer.

Not everyone objects to the mine. "It doesn't bother me," says Jim Kreibich, who lives closest to it and whose business, Jim's Electric, is listed as a contractor for mining companies.

The mine's current owner, Mississippi Sand of Kirkwood, Mo., says it has tried to be sensitive to neighbors' concerns. It placed a seismograph at a house whose residents complained about blasting, and it tested the water of neighbors who said blasting had altered their wells.

In neither case, the company says, did it detect any problems. "We care about the local area," says Jason Gisel, a consultant for the company. "We're doing what's right out there."

For the Slabys, the sand rush could not have come at a better time. They faced foreclosure on their 284 acres until, they say, a lease with a mining company – an advance on sand yet to be mined – yielded enough income. "We needed to come up with more money than what we get from farming," Ms. Slaby says.

The Slabys are sensitive to the disapproval of some of their neighbors. But they say mining will improve their land for farming by replacing steep hillsides with gentler slopes. They say they will mine only small areas at a time and reclaim them quickly. "We don't have to rape and pillage the land," Kyle Slaby says.

Other people are not so sure. In January, environmental groups in Wisconsin began circulating a petition calling on the state to ban sand mining altogether.

But mining experts expect the demand for frac sand to only grow. Plus, a cold winter and rising natural gas prices may set off a burst of new drilling in the spring. Mr. Lien is bracing for a busy – and contentious – time once his county's halt on new mining ends this summer.

"I'm guessing that at the end of the moratorium, the floodgates will open," he says.