Times Square: How safe is New York's 'Crossroads of the World'?

Loading...

| NEW YORK

As he stands in Times Square, tourists streaming past, Sgt. Ed Mullins of the New York Police Department points to vendors selling drinks and T-shirts out of plastic bins.

“Are we paying attention to them? Are we really paying attention to these boxes and what’s in them?” questions Sergeant Mullins, who is also president of the Sergeants Benevolent Association, the second largest police union in the city.

During a walking tour of the area, he turns to some new solar-powered trash containers, which have the ability to compress trash but are not transparent.

“Look, no one is paying attention to that. You can put a Pepsi can in there but what else goes in there? We don’t know,” he says.

The sergeant’s questions are not necessarily rhetorical.

The Times Square “bow tie," which encompasses about 13 blocks of tourist attractions, theaters, and office towers, has been a destination for potential terrorists as well as millions of tourists. In 2010, Faisal Shahzad, an immigrant, tried but failed to detonate explosives packed into an SUV parked in the crowded area. And, before they were stopped, the alleged Boston Marathon bombers are reported to have decided to drive to New York to try to set off their deadly explosives in Times Square.

So, just how safe is the city’s No. 1 tourist attraction?

The truth is that city officials are not sure.

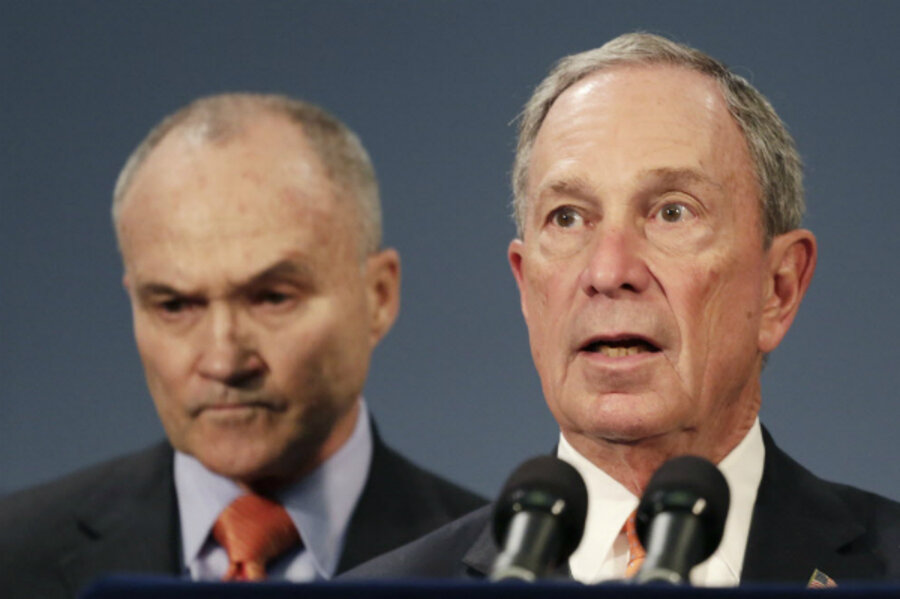

Shortly after Tamerlan Tsarnaev had been killed and his brother, Dzhokhar, had been wounded and captured, Mayor Michael Bloomberg said, “We don’t know that we would have been able to stop the terrorists, had they arrived here from Boston. We’re just thankful we didn’t have to find out.”

On Tuesday, New York Police Commissioner Ray Kelly, speaking at The Atlantic magazine’s New York Ideas Forum, said, “There is a constant stream of individuals trying to come here and kill us.”

Mr. Kelly credited “sheer luck” as well as the city’s huge investment in counterterrorism with helping to keep the city relatively safe. “Our camerawork is very important,” said Kelly.

Indeed, Mullins points to a light pole at Seventh Avenue and 44th Street that has multiple cameras mounted on it. Only a block away, another pole has air monitors that can detect chemical exposure as well as radiation levels. Security cameras belonging to private companies keep track of foot traffic moving past their entrances.

Mullins says some of the cameras use sophisticated “facial recognition” software that makes it harder for a “wanted” individual to just blend in with the crowd. According to Kelly, some of the cameras have technology to quickly spot a package that is left unattended in a crowded area.

However, Mullins says it would be dangerous to just trust a bunch of cameras. “The technology will only be as good as the people monitoring it,” he explains. “If there is a package here and I see it 10 minutes later and no one is around it, I should do something about that, you know.”

There is no doubt the area is flooded with a large variety of police. On a sunny day, cops sitting on horses peer above the crowds. A K-9 team is watching people go by on the east side of Times Square. Every block or two, uniformed police are on patrol. Mullins, who is wearing a suit not a uniform, says there are plenty of plainclothes police roaming the area. The city’s antiterror SWAT teams are often seen cradling automatic weapons as they move around the neighborhood.

Many of the police, although not all, work out of a police precinct called Midtown South, which Mullins says is the busiest in the world. “We have multiple roll calls everyday, there are hundreds of cops,” he says. “This is a 24/7 location and there are always cops up here.”

All the police are in the area, even though it is far from a high crime district. Brooklyn and the Bronx have the highest murder rates, according to the city’s crime statistics.

It hasn’t always been that way. In the 1970s and '80s, Mullins recalls, the crime rate in the area was very high.

“It was full of violence, prostitution, and narcotics,” he says. The whole area had a certain seedy character to it with pockets of adult bookstores. Today, almost all those elements are gone.

But, as it has been in the past, Times Square – named for the venerable newspaper – is a high profile part of New York. Between 350,000 and 450,000 people move through the district each day, according to a recent pedestrian survey conducted by the Times Square Alliance, which had no comment for this story. On New Year’s Eve, some 1 million people will squeeze into the area to watch the ball get lowered from the top of One Times Square.

In order for those celebrators to get into the Times Square area, they get their backpacks and purses inspected at police checkpoints. Doing that on a daily basis would probably not be doable, says Mullins.

Instead, he says, “the greatest tool we have to combat terrorism is every individual citizen. The best thing that could happen is if we all agree to pay attention and say something if something does not seem right.”