If you could literally watch yourself wasting energy, you might embarrass yourself into reducing your carbon footprint. It's a simple idea – monitoring use of energy in real time, with technology that measures appliance by appliance how much electricity is used – that has complex implications, says Shwetak Patel.

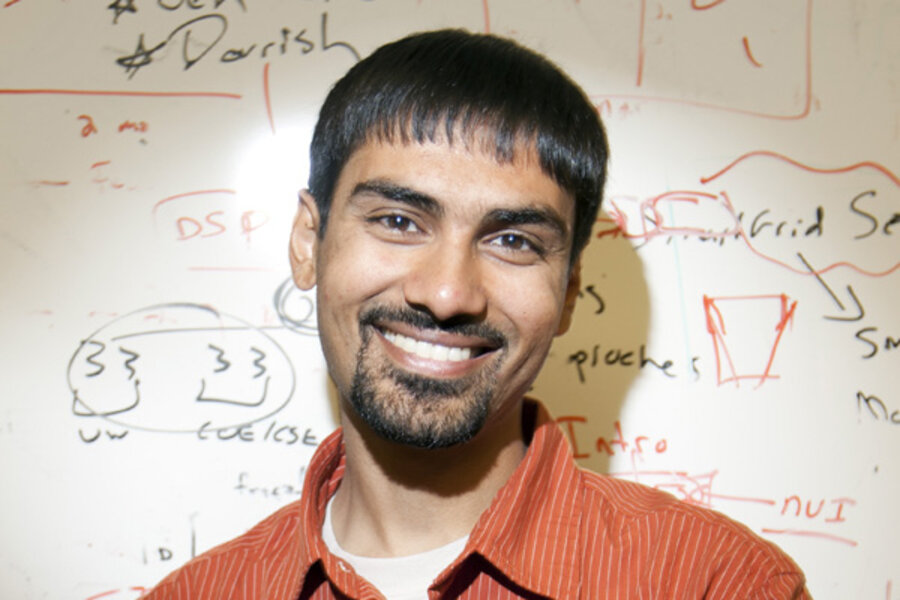

"I asked myself, what role can computer science play in improving things like global warming and the environment, and it turns out it's a core role," says the 29-year-old Patel, who teaches at the University of Washington, Seattle, and is a 2011 MacArthur Fellow.

Mr. Patel is creating easy-to-install technology that measures energy and water use. When the energy sensor is plugged into an outlet, it measures how much each appliance – from the refrigerator to the DVR – consumes, and every month a list is generated showing detailed electricity consumption.

"The idea is that if you give someone itemized feedback on energy and water consumption you see sustained reduction in behavior," says Patel, who estimates a 10 to 15 percent reduction of energy consumption among those using his device. "To be able to hit that just through behavior change is huge."

"[T]he problem is when people say we need to reduce our carbon footprint. We have no clue how to do that as individuals," he says. Patel believes that the biggest energy consumers are counter-intuitive. For example, it's not the workhorses like computers that we're on constantly; it is the "passive" devices that ratchet up the energy bill, like lighting or the cable box.

"Empowering individuals to monitor their energy will help everyone do his or her part in saving energy globally," he says.

– Whitney Eulich

Next: Chris & Kim Corbin, Luke & Sally Gran: Progressive planters