'Getting' and the constants of human nature

Loading...

How do you really feel about the little word get?

Isn’t it too useful to do without? That would be my take. But in a recent posting in the Copyediting blog, editor Erin Brenner noted that get figured prominently in the “pet peeves” discussion in her recent Copyediting II course. (It sounds like a regular feature of the course. I’m not sure what that says about editors.)

One student told of a former manager who had such a strong feeling against get – and wouldn’t use it himself – that her reflex now is always to “query” it, as editors say: to pester, er, ask the author to provide another word. Another student, forbidden to use get in his writing in high school, likewise internalized the prohibition: “I’m inclined to agree that there’s usually a better word,” he told Ms. Brenner.

She responds: “If there’s a better word, we’re not using it often enough.” Get goes back to circa AD 1200 in print, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. It would have been in use in speech even earlier, I would add. The American Heritage Dictionary records “21 current senses of get, many with subsenses; 20 phrasal verbs containing get, also with many subsenses; and another 20 idioms, again with many subsenses,” Brenner goes on to relate.

Yes, you can generally find a more highfalutin (a higher-falutin?) word for get if you reach. But why reach when a perfectly good word is right before you on the worktable?

The trick with get is that some of its usages are perfectly suitable for “standard” English and some are more informal. It takes a careful wordsmith to note the difference.

“Arise, get thee to Zarephath,” the Bible records the Lord saying unto Elijah the Tishbite (I Kings 17:9).

Compare that concrete directive usage (a term I’ve just made up) with the very informal “Get outta here,” as a response to an unbelievable statement: “Your kid got into Harvard? Get outta here!”

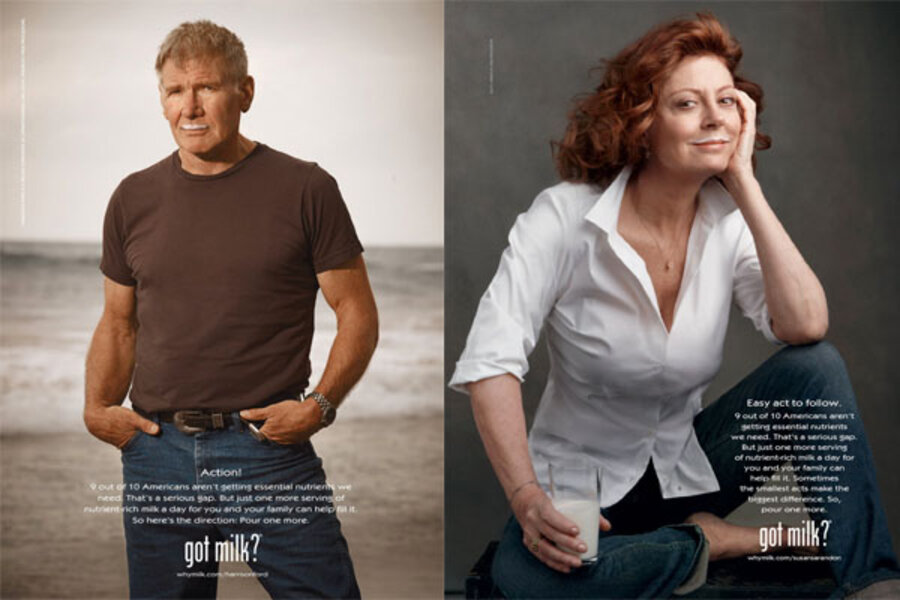

Similarly, it’s hard to imagine the successful (and much riffed-upon) “Got milk?” ad campaign having quite the same punch had the tag line been “Do you have milk?” – as the pet-peevish types would perhaps have preferred.

Get is one of those verbs, along with take, set, come, go, and a number of others, much used, in many senses, that have a special place in the language. It may be precisely their versatility and their potential range in tone that makes them so foundational.

They’re like the original part of a much-added-onto stately house, with its Norman French wing, dating back to the 11th century; its Neo-Latin scientific wing, begun during the Renaissance and still being added to; and the slang summerhouse, out in the garden. However fascinating the additions, the original is still the heart of the house.

And some of those original meanings have proved remarkably durable. A talk-show booker may refer to a prize guest for an interview as “a real get,” for instance. The Online Etymology Dictionary reminds us that get, as a noun meaning booty or prize, goes back to the 14th century.

When the biblical book of Proverbs urges, “with all thy getting get understanding” (4:7), we see an awareness of “conspicuous consumption” centuries before Thorstein Veblen came onto the scene.

If the meanings that some of those older words convey go back centuries, it may be because the human nature they refer to goes back even further.