'The Martian' is entertaining but lacks awe

Loading...

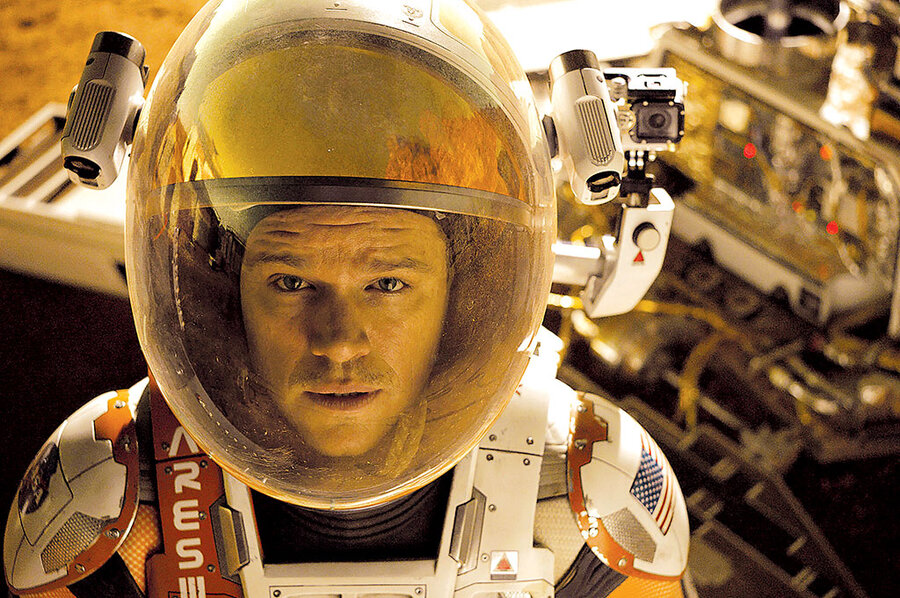

When I first heard that Ridley Scott would be directing the movie adaption of Andy Weir’s science fiction novel “The Martian,” starring Matt Damon as a NASA botanist stranded on Mars after a sandstorm forces his crewmates to abort the mission, I assumed we were in for another outer space gorefest a la “Alien.” Instead, what we have is almost jocular – a semiserious survivalist jaunt studded with wisecracks.

In some ways, this is a relief. After intergalactic thudders like Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar,” that black hole of ponderosity, I was more than willing to sit back and enjoy a no-frills space adventure without all that metaphysical hoo-ha.

For much of the way, Scott’s 3-D movie, which takes place over two years and was written by Drew Goddard, plays like a nuts-and-bolts manual for how to stay alive, Robinson Crusoe-style, on Mars. Damon’s Mark Watney, left for dead after being impaled by a communications antenna some 18 “sols” (Martian days) into the mission, manages to subsist on the Red Planet through sheer force of cunning. Even though, as a botanist, he was the least tech savvy of his crewmates (played by, among others, Jessica Chastain and Michael Peña), his skills prove indispensable in isolation.

He recycles his own waste to fertilize potatoes, burns rocket fuel to create water, and in general manages to create enough sustenance to theoretically last him until the next planned mission nearly four years away – that is, until the inevitable disasters (Martian frost, chemical explosions) upend his plans. Eventually, after much NASA haggling, a round-trip rescue mission is engineered by his earthbound crewmates, who were late in learning of his survival and guilt-ridden at having left him behind.

Mark’s survivalist spunk is so upbeat it’s almost creepy (though not intentionally so). He jokes to himself in homemade videos and ruefully notes that his only source of entertainment are the disco hits and “Happy Days” tapes left behind by his crew. While he occasionally mentions in passing that his chances of staying alive are slim, for the most part he’s sunny and upbeat. (Had he already read through the script?) He takes perverse pride in the fact that, on this planet, whatever he does or wherever he goes, “I’m the first.”

Entertaining as the movie often is, this all-American, can-do attitude is also the source of its shortcomings. Given the enormousness of its subject, there is a radical lack of awe in this movie. Norman Mailer once groused about Apollo 14 astronaut Alan Shepard’s hitting a golf ball on the moon, as if the act was insufficiently respectful for such a transcendent enterprise. I kind of agree. The same problem exists in “The Martian,” which is also transcendence-challenged. The film showcases Mark as a spunky jokester, conveniently without even a family back home to pine over. He’s a gumption machine. (The film’s anthem, I’m sorry to say, is Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.”)

Although the film is pretty good at being scientifically sound without boring us, its optimistic agenda goes awfully easy on the actual conditions on Mars. In a recent New York Times op-ed titled “Let’s Not Move to Mars,” writer Ed Regis, pooh-poohing futuristic talk about colonization of the planet, calls Mars “a veritable hell for living things, were it not for the fact that the planet’s average surface temperature is minus 81 degrees Fahrenheit.” Obviously he didn’t figure on Mark and his fertilized potatoes.

The question of just how transcendent sci-fi movies should be is a tricky one. I thought “Gravity,” not nearly as scientifically sound as “The Martian,” was just fine as long as the astronauts were loop-the-looping in broad arcs through silent space. It’s when George Clooney and Sandra Bullock opened their mouths, and out popped Hollywoodspeak, that matters came crashing earthward. Sci-fi movies that try to be trance-outs, like Stanley Kubrick’s “2001” or Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Solaris,” are at the opposite end of the sci-fi movie spectrum from “The Martian.” They get the awe part all right, but just as often they up the snooze factor.

Perhaps the best mix, for me, was Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” which at least fit my temperament for this sort of thing: It was extravagantly funny but also awestruck with wonderment about the great beyond. Scott, for all his visual panache, has never been a depth-

diver. His movies, even the most effective of them – “Blade Runner,” the most harrowing New World dystopia on film – are all on the surface. “The Martian” plays to both Scott’s strengths and weaknesses. By relegating Mark’s predicament to a purely survivalist scenario, he keeps things humming along without ever widening the horizon. But there was an obligation to widen the horizon. I didn’t come out of this movie humbled, awed, frightened, or transported. Scott is hitting golf balls in the galaxy. Grade: B (Rated PG-13 for some strong language, injury images, and brief nudity.)