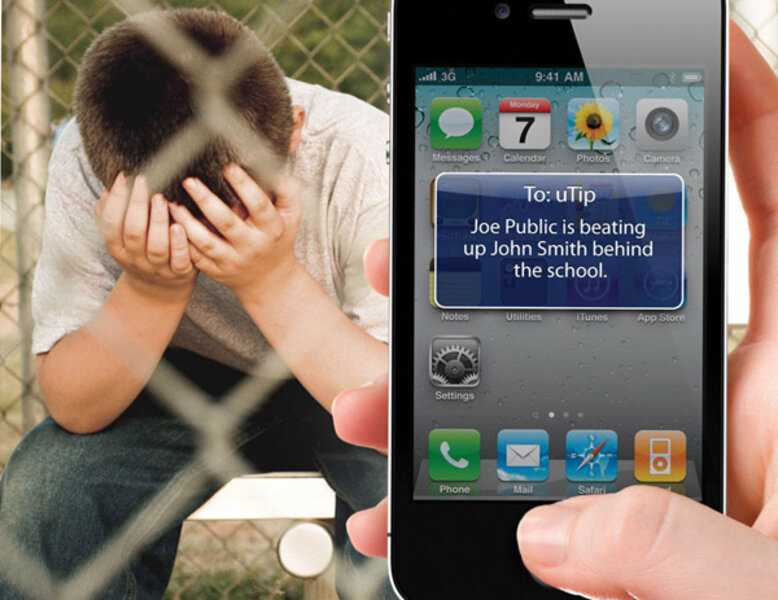

Social media, the Internet and cell phones have certainly changed the bullying landscape. Children today have a far harder time finding respite from bullying; what might have once taken place only at school can now follow kids home on their cell phones, Facebook pages, and e-mail accounts. The Internet also provides a slew of opportunities for people to be mean, from slam boards (no-holds-barred college gossip sites), to fake Facebook accounts. Add to that some scary statistics – such as the National Crime Prevention Council’s finding that more than 43 percent of teenagers have been the victims of cyberbullying – and it would be easy to focus anti-bullying attention on-line.

But many researchers say that the vast majority of bullying still takes place in person – in the classroom, the schoolyard, and the cafeteria. Much of the on-line bullying, they say, is an extension of what starts face to face; studies also show that students report in-person bullying to be more damaging.

Many of the high cyberbullying statistics may come from the way different studies define “bullying,” which in some surveys is described as anything from a mean text message to an unauthorized forward to another teen blocking the victim from his or her Facebook page. (Academic and legal definitions tend to require more components for behavior to qualify as bullying.) A recent survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project found that 15 percent of teens who use social networking sites say they have been the target of mean or cruel behavior there; 69 percent say their peers are mostly kind to one another.