National Portrait Gallery explores what makes someone 'cool'

Loading...

What is cool? Or perhaps, more importantly, who is cool?

Whatever or whoever it is, cool is sought, that’s for sure. The pursuit of cool underlies the worlds of entertainment, fashion, and advertising – i.e. most of modern popular culture to a remarkable extent – and is arguably one of the key drivers of American society.

Now an attempt to define the elusive meaning of cool is the focus of a mainstream exhibition. The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. currently has on show an exhibit titled “American Cool,” which is comprised of 100 photographic portraits of individuals deemed by the curators to embody the concept of cool in a uniquely American way. Joel Dinerstein, an author and professor of American Studies at Tulane University, and Frank H. Goodyear III, co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and former curator of photography at the Portrait Gallery, organized the exhibit and wrote the accompanying book.

What does it take to get into this pantheon of cool? That's a burning question and the exhibition provides a clue as to what cool is and how to be it.

As might be expected, a lot of actors and musicians are included. What makes them cool? One critic called Humphrey Bogart "the most iconic American male actor in history," according to the caption of the photo of Bogart, and Lauren Bacall was called "hot as pepper, cool as rain, dry as smoke" by one critic, according to her photo's caption. What makes the actors somehow exude cool even for generations which succeeded them?

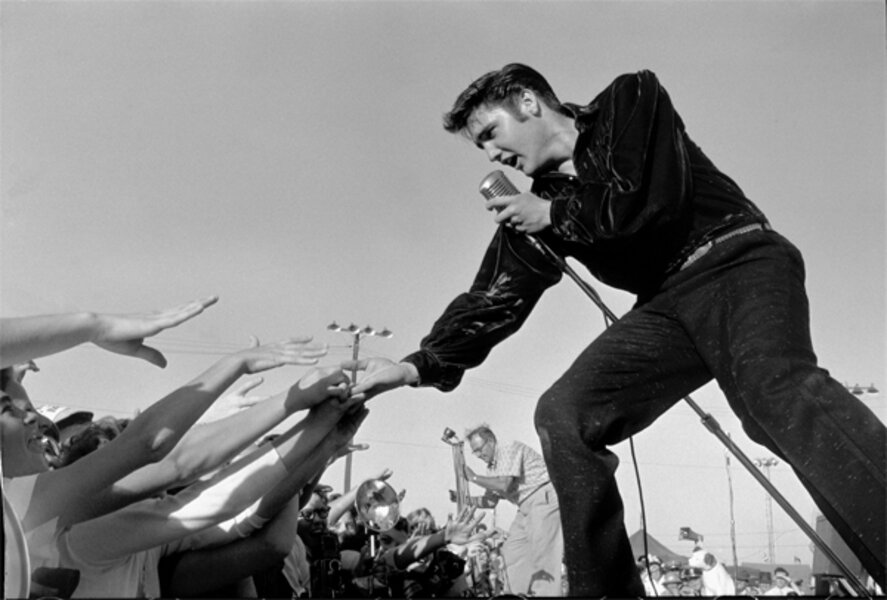

Photos of Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan are on show. Was it their groundbreaking, original approach to modern music that landed them in the exhibit?

A few writers are pictured, Jack Kerouac and Ernest Hemingway among them. Were they chosen because they were rebels and renegades and thus considered cool?

More than a quarter of the exhibit portraits in the show are of African-Americans, beginning with Frederick Douglass and on to Duke Ellington, Michael Jordan, and Billie Holiday, among many others. What place does cool have as a cultural tradition in the black community?

Though cool was initially considered to be an exclusively masculine quality, the concept expanded over time and almost a quarter of those pictured are women, including Greta Garbo, Georgia O’Keefe, Bessie Smith, Mae West, Angela Davis, and Madonna, to name a few.

So what is it? In the exhibit's book, Dinerstein and Goodyear developed the following rubric for being cool: 1) “originality of artistic vision” and “signature style"; 2) a quality of "rebellion or transgression”; 3) “iconicity” (in other words, being famous); and 4) producing a "cultural legacy." Therefore, the answer to the above questions about what it takes to be cool is yes, those qualities are some of what it takes to be considered cool, at least in the terms of this exhibit.

The origin of the word and concept of cool can be traced back to African culture and one scholar claims that the concept of cool can be found in 35 Central and West African languages. The idea of American cool really began among jazz musicians in the 1940s, a time when African-Americans were not treated as equal. Cool became a pose, an attitude, a mask which initially helped black artists deal with this atmosphere of racial oppression. It was seen as a quality related to the idea of being “hip” and having “charisma without trying” but including more than either. It was about maintaining emotional equilibrium under pressure, including racial oppression, and being stylish while doing it.

In this exhibit, the jazz saxophonist Lester Young is credited with being the “father of cool,” for bringing the African concept into the American vernacular. Other jazz musicians, including Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis, contributed to the idea.

Gradually, cool became embraced by most Americans, regardless of color. “Americans care about cool,” says Dinerstein. Therefore some Americans have tried to market it. According to this exhibit, cool is a commodity, or has become one. "Over the past century, cool has arguably been America's chief cultural export, " says Goodyear in his essay on the photography of cool in the exhibit's book.

It’s not enough just to be cool. Others have to know and acknowledge you are. Being photographed as cool is a large part of being so. As Dinerstein points out, “If we could not find a photograph that captured a person’s cool, he or she was dropped.”

An interesting, but unofficial, subplot of this exhibit is the extent to which the use of tobacco is pictured as a prop for cool. Approximately 10 percent of the photos depict the subject smoking. In addition, the captions which accompany the portraits indicate that at least one in five of those pictured had issues with substance abuse. Looking deeper into the relationship between those propensities and American cool might be instructive.

And finally, there is the question of you and me. Are we cool? If not, can we become so? “Most of us simply aren’t cool,” Dinerstein proclaims. And maybe that’s okay. Because, looked at closely, this exhibit gives hints that being cool is probably a little more complicated than most cool people would like us to think.

“American Cool” is at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. until September 7, 2014.

Katherine Stephen is a Monitor contributor.