Vivian Maier: Amateur with a Sharp Eye

Loading...

| Chicago

The story of Vivian Maier's life is as captivating as her photographs, and for many of the same reasons. Her images give us a little and we want more: a woman's hands clutched behind a polka-dot dress; a birthmark on a spindly leg; a man with few teeth eating hungrily perched on a curb. From New York to Chicago, Paris to Cairo, Maier captured the quotidian, causing us to notice what we otherwise wouldn't notice, offering glimpses into humanity that are revealing but limited, intimate yet detached.

What we know about Maier is sparse. She was a nanny with a camera, a caretaker, and a collector. She read newspapers voraciously. She had strong opinions about politics and film. She wore clunky shoes and walked with a stride that meant business. Though one family Maier worked for has described her as a Mary Poppins-type, others remember her as something of a recluse, private and often abrupt.

Now, two years after her death, her legacy has taken a dramatic turn.

"She's been broadcast across the entire globe. Millions of people are looking at her work," says Joel Meyerowitz, photographer and coauthor of "Bystander," a seminal book on street photography.

Born in New York in 1926 to a French mother and Austrian father, Maier grew up in France and the United States. As an adult, she traveled the world but eventually settled in the Chicago area, working as a nanny in various households in the city's North Shore suburbs. The unofficial spokesman for her work is John Maloof, a young former real estate agent who bought 30,000 of her negatives for around $400 at an auction in 2007.

Though Maier was alive at the time, many of her possessions were for sale due to her delinquency in paying for a storage locker. When she died in April 2009, she had no idea what had become of her work, nor of the interest it was beginning to stir.

Colin Westerbeck, director of the California Museum of Photography and coauthor with Mr. Meyerowitz of "Bystander," credits Mr. Maloof for the intense interest Maier's work has created. "He's been a considerable posthumous press agent. He's got the website, and he's contacted a lot of people, and his distribution and talking up of the work is a lot of what's given exceptional interest to the work."

While it's true that part of the allure of Vivian Maier is the story behind her work, her photographs have a quiet but powerful presence. She has captured stolen moments – ones that would have disappeared were it not for the click of her shutter; ones that address themes of poverty and resilience, connection and loneliness.

Maier's photographs reveal an elevated sensibility, says Meyerowitz. "They show somebody with a great humanism, a great sense of being disciplined about making the work, and yet she's found a way to be invisible. She's tough. She gets out there into tough neighborhoods and maybe potentially difficult situations, and she stands her ground and makes these photographs. They're elegant and well timed and beautifully felt."

Maloof hasn't been the only one keen to broadcast Maier's work. Ron Slattery was another initial buyer, and though he has since sold a significant portion of his collection, he still has some original work. Another buyer is Jeff Goldstein. Together, Mr. Goldstein and Maloof have the majority of Maier's work and are working to archive and promote it.

Maloof's collection includes about 100,000 negatives, 3,000 prints, hundreds of rolls of undeveloped film, audio recordings, and film reels. Goldstein has about 15,000 negatives, 1,000 prints, 24 homemade movies and numerous slides.

In addition to sorting and archiving his vast collection, Maloof is the editor of a forthcoming book of Maier's photographs and is in the research phase of a film about her life.

Nancy Gensburg, a former employer who first met Maier in the 1950s, says, "She was not easy to understand but she had a lot to give, and I think she's giving it through her photographs." Maier worked as a nanny for the family for 17 years and instigated many adventures, Ms. Gensburg recalls, from picking strawberries to catching rides to school on the milk truck.

"She just would not conform – no rules, just her rules," Gensburg says. When Maier's motor scooter was confiscated because she considered a driver's license an invasion of privacy, Maier turned to hitchhiking.

Since Maier's death, no relatives have come forward, and none of the families Maier worked for recalls her maintaining family relationships. A 1930 census report and a 1936 obituary from The New York Times, however, suggest that Maier had an older brother. What became of him – and Maier's father – is not clear. Maier was raised by her mother, Marie, and for a time the two shared an apartment in New York with French photographer Jeanne Bertrand.

"She seemed to actually enjoy being a bit of a mystery," says former employer Karen Usiskin, who knew Maier in the mid-1980s and remembers her as frugal and private, strict and efficient.

Though Maier was a prolific photographer throughout her adult life, few people knew her work. Her closest encounter with fame was brief employment in the mid-1970s for then-television host Phil Donahue.

"I remember my first meeting with her because she took my picture," says Mr. Donahue, who was raising four boys as a single dad at the time. One photo that Maier took of the family during this time was of Donahue putting a cake on the table for his youngest son's birthday; another was of the same son, Jimmy, watching his father on television.

"I just figured it was a hobby. It never occurred to me there might be something valuable about her work," Donahue says. "I guess now we wait and see how this rare wine found in the cellar is going to sell."

And this is the other big question. How much is Maier's work worth, and who decides?

Westerbeck and Meyerowitz – who are considering including Maier in a revised edition of "Bystander" – agree that it's a good story but they need to see more of her work before making a serious evaluation.

"I think that in historical perspective the photographs are not in and of themselves a revolutionary discovery," Westerbeck says. "Part of the interest in it is a combination of the images and intensity with which she did this with the seemingly rather quiet and almost withdrawn life that she led."

"I'm not a forecaster of what will last, although I am moved enough to try to give her the leverage of being taken seriously in a history book," says Meyerowitz.

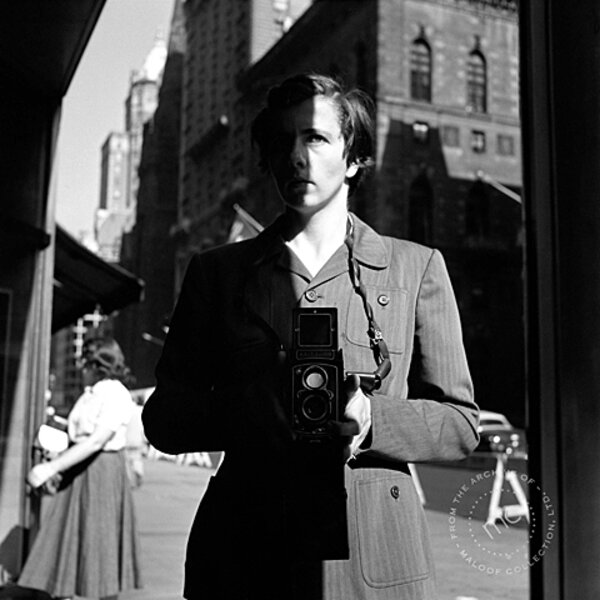

Perhaps the most accurate view of Maier comes from her self-portraits. "She's looking in the windows at her own reflection or in the mirrors and she'd hold her ground with a kind of fierce independent intelligence and an open gaze," says Meyerowitz. "This is a strong and determined person who is reading the world around her and making critical decisions about the values and the humanity of everybody."

In our contemporary era of tell-all, Maier's apparent disregard for recognition, or even understanding, makes her story that much more compelling.

"She was doing it for the thrill of getting out of the house with the kids, being in the world at large, and feeling the richness of life as it disappeared every few seconds right in front of her," says Meyerowitz. "That's what photography does. It holds onto these epiphanies that appear and disappear right in front of our faces."

Like the epiphanies captured in her images, Maier appeared and disappeared from people's lives and homes, arriving with boxes full of photos and leaving with even more. Maren Baylaender, whose husband employed Maier as a caregiver for his daughter from 1989 to 1993, sat at the dinner table with Maier for years and considers the story a lesson not in photography but in our own boundaries.

"We get fooled in our lives and meet people and put them into one category and then they become something completely different," she says. "When I saw those pictures I said, 'What a shame. We could have had such wonderful conversations.' "