An Ice Age on Mars is ending, scientists say. Why is that important for Earth?

Loading...

Though it doesn't seem like much happens on Mars – a barren desert of a planet – it does experience seasons and climate change, much as Earth does.

In fact, the Red Planet is going through a change now, as it is coming out of an ice age, say geologists from the Southwest Research Institute.

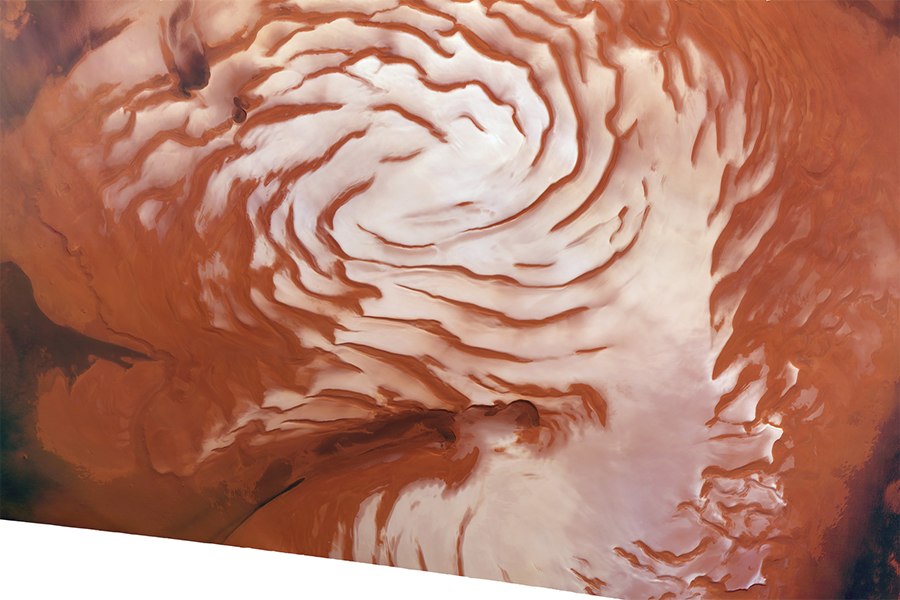

An analysis of radar data collected by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows that about 87,000 cubic kilometers of ice have accumulated at the poles since the end of the last ice age about 370,000 years ago, they report in a paper published Thursday in the journal Science. That would be enough to spread a 2 foot thick layer of ice across the entire surface of our solar-system neighbor, a rocky planet that is about half the size of Earth.

The volume and thickness of the Martian ice matches model predictions made by other scientists over a decade ago.

"Turns out the models were pretty good," says Isaac Smith, a postdoctoral researcher at the San Antonio-based research institute and lead author of Thursday's paper, in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. "This is how we start putting dates on things; combining observations with models," he says.

Dr. Smith didn't set out to prove Martian climate models when he sought to measure ice on the Red Planet.

"I just go where the layers tell me to go," he tells the Monitor.

But when his team started measuring, they realized their findings validated earlier predictions, which is a boost to the same type of climate modeling that is used on Earth. Smith is now at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory working with glacial modelers who are studying Antarctica, where sea ice is behaving mysteriously compared to Earth's North Pole.

By Earthly standards, the climate is quirky on Mars. There, polar ice caps actually grow during warmer periods, unlike on Earth, where they melt into the oceans. That is largely because of the tilt of Mars's axis. It can shift by as much as 60 degrees over hundreds of thousands to millions of years, exposing different parts of the planet to the heat of the sun. The Earth's tilt varies by only about 2 degrees over the same period.

When Mars is tilted 60 degrees, its North Pole faces the sun. This kicks off an ice age, as warming at the poles causes polar ice to turn to water vapor, get absorbed by the planet's thin atmosphere, and then be transferred to the cooler mid-latitudes where it condenses into snow or frost.

On Earth, by contrast, ice ages bring polar cooling. Ice sheets build up by drawing water from the oceans, which don't exist on Mars, although they may have billions of years ago.

Right now Mars is tilted about 25 degrees, almost the same as Earth's 23 degree tilt. In radar images, Smith's team is finding ice between 30 and 60 degrees latitude on the otherwise dry and dusty planet.

The icy patch is "kind of like Texas to Canada in size," he says. "There's ice there now, but it's being removed." The ice is moving to both Martian poles, though mostly to the North Pole. Smith's team doesn't know why all the action is there.

"Why does South Pole not exchange the ice with the rest of planet?" Smith wonders. "These are things we want to work on in the future, to figure it out."