How origami can make solar panels more efficient

Loading...

A new technique to harness solar energy by using kirigami solar cells was announced in a paper published Tuesday in the journal ‘Nature Communications.’

Kirigami is a variation of origami, the Japanese art of paper folding. Unlike standard origami, kirigami allows for the paper to be cut, as well as folded.

The flat design of traditional solar panels limit the panel's surface area, reducing potential efficiency. Because the sun moves continuously, researchers at the University of Michigan used kirigami to create a contracting lattice structure that follows the source of solar energy as it moves throughout the day.

When tested at a solar panel farm in Arizona, the kirigami panel produced 36 percent more photovoltaic energy compared to a traditional panel.

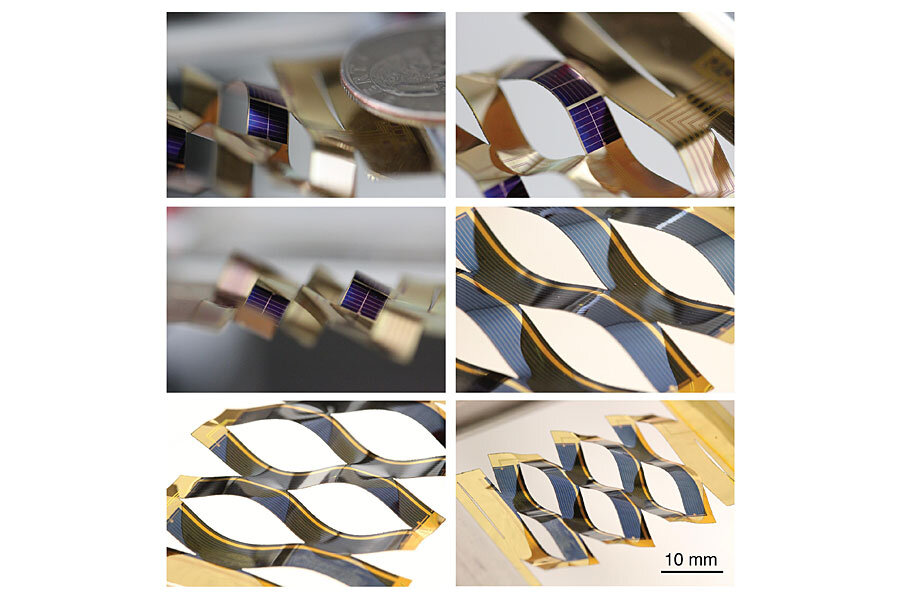

Solar panel efficiency has been addressed before, but the motorized assemblies designed to rotate the panels with the sun make the systems more expensive and too heavy to install on rooftops. But with kirigami panels, the cut plastic strips (and the solar cells on them) twist over a radius of 120 degrees when the panel is stretched, allowing the cells to face toward the sun as the panel stays stationary.

“We did try a lot of patterns, and it turned out that this simple pattern was actually one of the best,” explains Max Shtein, one of the authors of the published article and an associate professor of engineering and materials science at the University of Michigan. “It has this property where it kind of moves out of its way and prevents shadowing.”

There is a design tradeoff, however. Kirigami panels would have to be twice as big because “You’re stretching the solar cell, so you have to have room to stretch it into,” explains Shtein. But until the strips began twisting with the sun, the panels wouldn’t look any different from conventional ones.

Although Shtein is confident about the versatility of kirigami-designed panels, other scientists, such as Keith Emery, who evaluates solar panel designs for the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, worry there are a lot of potential problems with the new design. Emery questions the material’s durability to extreme temperatures and extensive stretching.

Along with increasing energy efficiency, reducing the cost of photovoltaic systems is a significant goal for engineers.

“As we try and further and further decrease the cost of solar electricity and increase the amount of power we get, we will transition towards other types of geometries that have better performance and cost less,” says Shtein. “We think it has significant potential, and we’re actively pursuing realistic applications. It could ultimately reduce the cost of solar electricity.”

This is not the first scientific improvement to involve a form of Japanese origami.

Within the last few months, scientists at Arizona State University used kirigami to explore the possibility of flexible batteries and physicists at Cornell University shrunk kirigami down to the nanoscale to potentially create the smallest machines ever seen by mankind.