Where did all that cosmic dust come from?

Loading...

Giant dust clouds seen in the early universe may have been created by exploding stars, a discovery that suggests supernovas were prolific space dust factories for ancient galaxies, scientists say.

This finding, which was made by the SOFIA flying observatory, may shed light on how the dust that helped form countless stars and galaxies was created, the scientists added.

The elements that make up everything from people to planets are essentially stardust. These elements are forged in stars by nuclear fusion, which fuse small atoms such as hydrogen and helium into larger ones such as carbon and iron. [Supernova Photos: Amazing Star Explosions]

For years, scientists have tried to explain the vast amounts of dust seen in the early universe. The leading explanation was that this dust was created by exploding stars known as supernovas.

However, researchers also thought supernovas should excel at shattering and destroying dust as well. Prior research suggested that up to 80 percent or more of the dust that supernovas might generate could get destroyed by the so-called "reverse shocks" of these explosions. Reverse shocks are shockwaves rebounding off the cold, dense matter surrounding supernovas.

"It's been known that 'we are all made of star stuff,' but the details of how newly formed 'star stuff' survives to later become the seeds for stars and planets is a bit murky," said lead study author Ryan Lau, an astronomer at Cornell University.

One potential alternative source of the ancient dust seen in the early universe was that "some less powerful stars that don't go supernova go through a phase where they gently blow off their innards and form dust," Lau said. "However, this way of forming dust isn't very efficient, because it takes a while for these less powerful stars to evolve to that point."

Now Lau and his colleagues have unexpectedly confirmed that supernovas can be dust factories.

"Finding this surviving dust is surprising to me because when I think of a supernova, I imagine a very harsh, violent environment that is very inhospitable to dust and other things that happen to be caught in the explosion," Lau told Space.com.

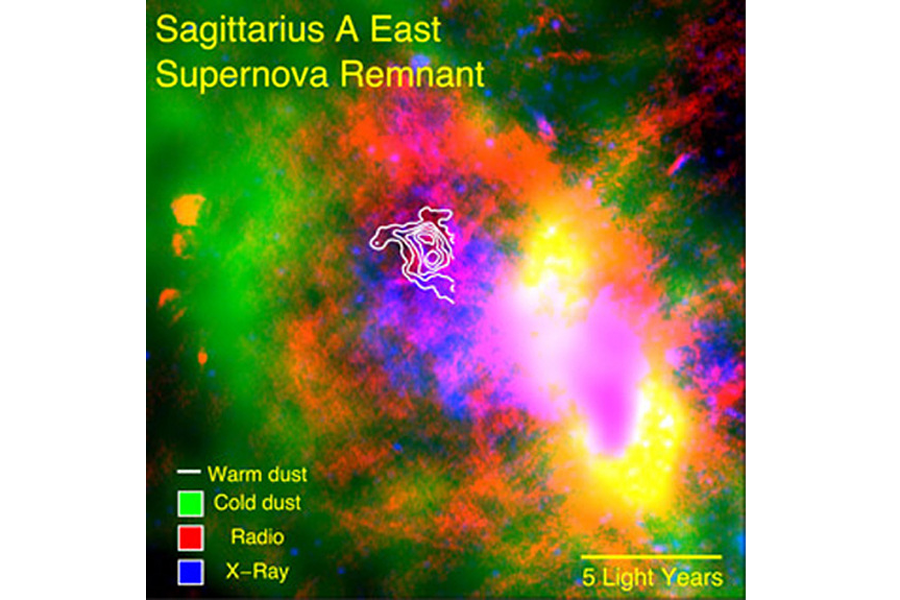

The astronomers employed the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center housed aboard a modified Boeing 747SP jumbo jet. They analyzed dust in the middle of Sgr A East, the remnant of a supernova located near the center of the Milky Way. This remnant, known as Sgr A East, is about 10,000 years old.

"We were on a flying observatory traveling at 600 mph (965 km/h) at an altitude of 45,000 feet (13,715 meters) to take images of a 10,000-year-old supernova remnant located 27,000 light-years away from us at the center of our galaxy," Lau said. "No other currently operating observatory other than the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy could detect this dust."

The scientists found that about 7 to 20 percent of the initial dust of the supernova survived its reverse shock.

"One of the most surprising things is that we were not expecting to see this at all," Lau said. "We were looking at the two brighter features to the right and to the left of the supernova dust we found."

The researchers suggest the dust survived the supernova's reverse shock because of dense gas surrounding the explosion, which slowed the debris from the supernova, helping the dust cool greatly and preventing its destruction. This finding implies that ancient supernovas could have generated the vast amounts of dust seen in the early universe.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (March 19) in the journal Science.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- We Live Within A Supernova Remnant - New Evidence | Video

- Star Quiz: Test Your Stellar Smarts

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.