Oil spills can stop tuna hearts, say scientists

Loading...

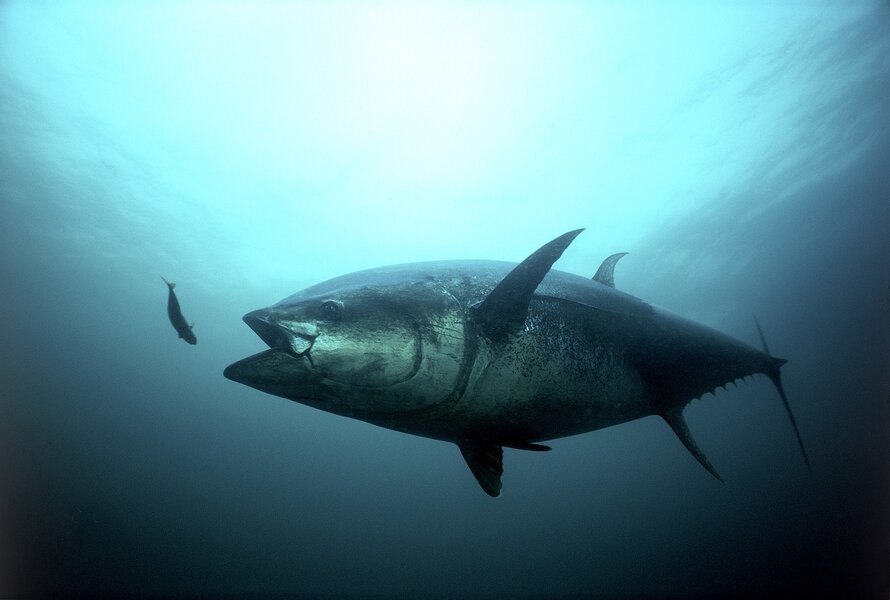

When the Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion sent plumes of crude oil billowing through the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic bluefin tuna who breed there were at the height of their spawning season, releasing clouds of eggs and milt into the open water. As they dove up and down in giddy distraction, oil coated a fifth of their breeding grounds.

Previous spills had taught scientists that oil cripples the hearts of young fish, but until now it wasn't clear how. A study published this week reveals that crude oil blocks the transfer of potassium through heart cells, a process that regulates the beating of almost all hearts.

"The ability of a heart cell to beat," explained Barbara Block, marine sciences professor at Standford University, "depends on its capacity to move essential ions like potassium and calcium into and out of the cells quickly. This dynamic process, which is common to all vertebrates, is called 'excitation-contraction coupling.' We have discovered that crude oil interferes with this vital signaling process essential for our heart cells to function properly."

Oil disrupts the ion channel pores through which those molecules traverse cell membranes, as they go about their work of regulating heart rate and contractions.

Scientists from Stanford and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration bathed tuna cardiac cells in low concentrations of crude oil, which were similar to what gulf tuna conceived during and after the 2010 spill might have encountered. Using electro-physiological techniques with names like "patch clamping" and "confocal microscopy," they recorded how ions passed through cell membranes and identified the proteins in those pathways that were affected by the chemicals in crude oil.

"The normal sequence and synchronous contraction of the heart requires rapid activation in a coordinated way of the heart cells," said Dr. Block. "Like detectives, we dissected this process using laboratory physiological techniques to ask where oil was impacting this vital mechanism."

So what happens to fish with clogged ion channels? According to the study, they suffer from slowed and irregular heartbeats that can lead to cardiac arrest.

"The protein ion channels we observe in the tuna heart cells are similar to what we would find in any vertebrate heart and provide evidence as to how petroleum products may be negatively impacting cardiac function in a wide variety of animals," said Block, noting that exposure to these hydrocarbons could lead to cardiac arrhythmias and bradycardia among many animals.

A report released last year by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) confirmed that the gulf's dolphins, sea turtles, and many fish including the Atlantic bluefins were in fact continuing to die in record numbers three years after the 2010 spill – which is considered the worst spill in petrochemical history. And the tuna were already imperiled by overfishing, which has led to tense international haggling over appropriate fishing quotas.

"As top-level predators, [western Atlantic bluefin tuna] are indicators of ecosystem health," reported the NWF, describing how the oil spill had jeopardized an already tenuous recovery. "For species in peril, reductions of reproductive success and lower populations can be major impediments to recovery."