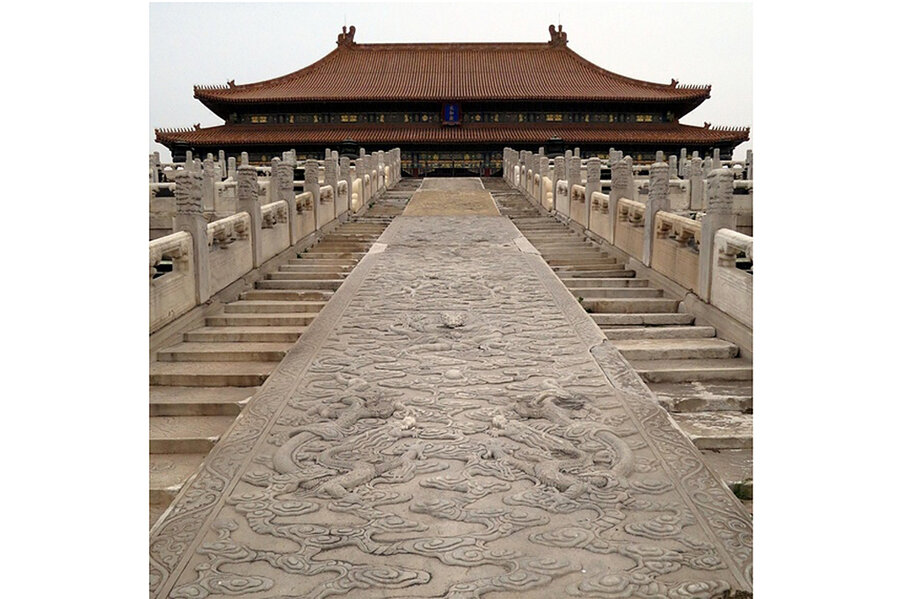

How did they move those 100-ton stones? Scientists solve Forbidden City mystery.

Loading...

The Forbidden City, the palace once home to the emperors of China, was built by workers sliding giant stones for miles on slippery paths of wet ice, researchers have found.

The emperors of China lived in the Forbidden City, located in the heart of Beijing, for nearly 500 years, during China's final two imperial dynasties, the Ming Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty. Vast numbers of huge stones were mined and transported there for its construction in the 15th and 16th centuries. The heaviest of these giant boulders, aptly named the Large Stone Carving, now weighs more than 220 tons (200 metric tons) but once weighed more than 330 tons (300 metric tons).

Many of the largest building blocks of the Forbidden City came from a quarry about 43 miles (70 kilometers) away from the site. People in China had been using the spoked wheel since about 1500 B.C., so it was commonly thought that such colossal stones would've been transported on wheels, not by something like a sled. [See Photos of the Forbidden City & Building Stones]

However, Jiang Li, an engineer at the University of Science and Technology Beijing, translated a 500-year-old document, which revealed that an especially large stone — measuring 31 feet (9.5 meters) long and weighing about 135 tons (123 metric tons) — was slid over ice to the Forbidden City on a sledge hauled by a team of men over 28 days in the winter of 1557. This finding supported previously discovered clues suggesting that sleds helped to build the imperial palace.

To discover why sleds were still used for hauling gigantic stones 3,000 years after the development of the wheel, Li and her colleagues calculated how much energy it would take for sleds to accomplish this goal.

"We were never sure quite what we would learn," said study co-author Howard Stone, an engineer at Princeton University.

The ancient document Li translated revealed that workers dug wells every 1,600 feet (500 meters) or so to get water to pour on the ice to lubricate it. This made the ice even more slippery and, therefore, easier upon which to slide rocks.

The researchers calculated that a workforce of fewer than 50 men could haul a 123-ton stone on a sledge over lubricated ice from the quarry to the Forbidden City. In contrast, pulling the same load over bare ground would have required more than 1,500 men.

Moreover, the researchers estimated that the average speed of a 123-ton stone hauled on a sled on wet ice would be about 3 inches (8 centimeters) per second. This would have been fast enough for the stone to slide over the wet ice before the liquid water on the ice froze.

All in all, the researchers suggested that workers preferred hauling stones on smooth, flat, slippery, wet ice rather than on a bumpy ride on a wheeled cart. The ancient document Li translated revealed there were debates over whether to rely on sledges or wheels to help build the Forbidden City — sledges may have required far more workers, time and money than mule-pulled wagons, but sledges were seen as a safer and more reliable means for slowly transporting heavy objects.

"It is humbling to think about a big project like this taking place 500 to 600 years ago, and the level of planning and coordination that was needed for it to occur," Stone told LiveScience.

Li, Stone and their colleague Haosheng Chen detailed their findings online Nov. 4 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

- Gallery: Ancient Chinese Warriors Protect Secret Tomb

- Gallery: Aerial Photos Reveal Mysterious Stone Structures

- In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.