Have scientists discovered a new element?

Loading...

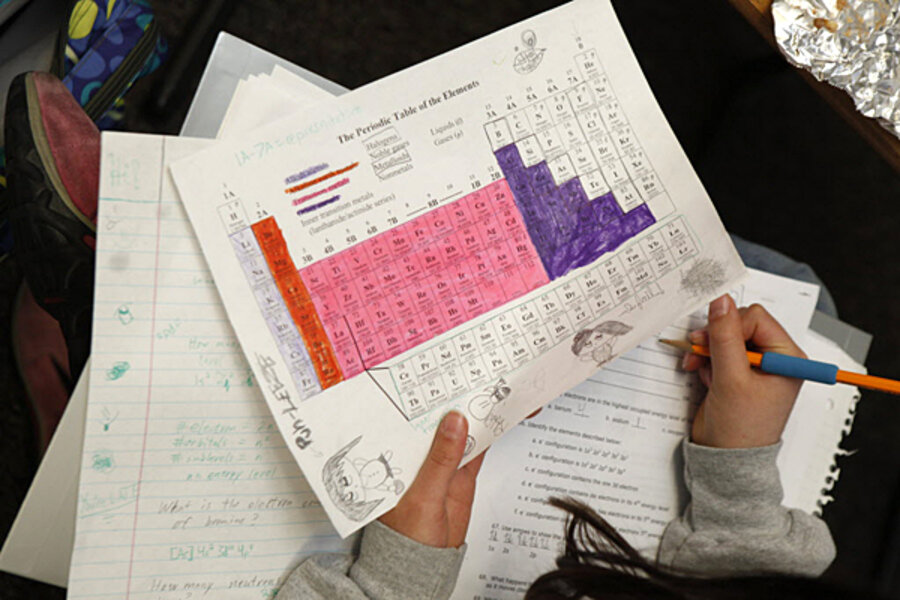

Scientists say they've created a handful of atoms of the elusive element 115, which occupies a mysterious corner of the periodic table.

The super-heavy element has yet to be officially named, but it is temporarily called ununpentium, roughly based on the Latin and Greek words for the digits in its atomic number, 115.

The atomic number is the number of protons an element contains. The heaviest element commonly found in nature is uranium, which has 92 protons, but scientists can load even more protons into an atomic nucleus and make heavier elements through nuclear fusion reactions. [Wacky Physics: The Coolest Little Particles in Nature]

Scientists hope that by creating heavier and heavier elements, they will find a theoretical "island of stability," an undiscovered region in the periodic table where stable super-heavy elements with as yet unimagined practical uses might exist.

In experiments in Dubna, Russia about 10 years ago, researchers reported that they created atoms with 115 protons. Their measurements have now been confirmed in experiments at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany.

To make ununpentium in the new study, a group of researchers shot a super-fast beam of calcium (which has 20 protons) at a thin film of americium, the element with 95 protons. When these atomic nuclei collided, some fused together to create short-lived atoms with 115 protons.

"We observed 30 in our three-week-long experiment," study researcher Dirk Rudolph, a professor of atomic physics at Lund University in Sweden, said in an email. Rudolph added that the Russian team had detected 37 atoms of element 115 in their earlier experiments.

"The results are by and large compatible," Rudolph said.

Super-heavy elements are generally unstable and most last only a fraction of a second before they start to decay. The scientists had to use special detectors to look for the energy signatures for the X-ray radiation predicted to be given off by element 115 as it quickly degrades.

A committee from the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which governs chemical nomenclature, will review the new findings to decide whether more experiments are necessary before element 115 gets an official name.

Some of element 115's neighbors have already been christened. Last year, the man-made elements 114 and 116 were named flerovium (Fl) and livermorium (Lv).

The new experiments will be detailed in The Physical Review Letters.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

- The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

- Gallery: Dreamy Images Reveal Beauty in Physics

- Facts About Rare Earth Elements (Infographic)

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.