Albert Einstein papers show physicist as lover, dreamer

Loading...

| Jerusalem

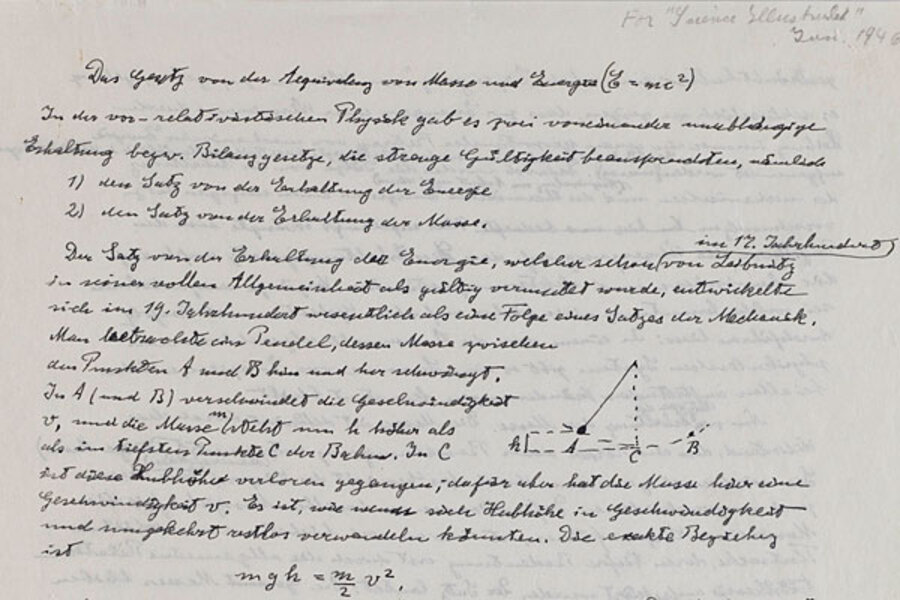

At speeds even he could barely imagine, Albert Einstein's private papers and innermost thoughts will soon be available online, from a rare scribble of "E = mc2 " in his own hand, to political pipe-dreams and secret love letters to his mistress.

Fifty-seven years after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist's death, the Israeli university which he helped found opened Internet access on Monday to some of the 80,000 documents Einstein bequeathed to it in his will.

It will go on adding more at alberteinstein.info and in time, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem says, it is committed to digitising its entire Einstein archive.

Among items likely to attract popular attention is a very rare manuscript example of the formula the author of the theory of relativity proposed in 1905, E = mc2 , where energy, E, equals mass times c – the speed of light in a vacuum – squared.

Once published, a cache of two dozen love letters to the woman who would become his second wife - but written while he was still married to his first - may also attract the curious.

So too may an idealistic proposal in 1930 for a "secret council" of Jews and Arabs to bring peace to the Middle East.

At present, only a selection of documents dating from before 1923, when Einstein was 44, are available. As papers are scanned, the bulk of them in Einstein's native German, the university will publish English translations and notes, said Hanoch Gutfreund, whose committee oversees the archive.

"This is going to be not only something to satisfy the curiosity of the curious," he said. "But it also will be a great education and research tool for academics."

Lover, dreamer

Some items, he acknowledged, were so personal that the archivists weighed carefully whether make them public.

Among these are 24 love letters the scientist wrote to his cousin, Elsa Einstein, with whom he conducted an affair for several years before finally divorcing his first wife, Mileva Maric, and remarrying in 1919: "If you let enough time go by," Gutfreund concluded, "Then it's kosher."

Also not yet included online, but now on display at the university, is a letter Einstein wrote in German to the Arab newspaper Falastin in which he proposed a "secret council" to help end Jewish-Arab conflict in then British-rule Palestine.

Einstein envisioned a committee of eight Jews and Arabs -- a physician, a jurist, a trade unionist and a cleric from either side -- that would meet weekly:

"Although this 'Secret Council' has no fixed authority, it will however, ultimately lead to a state in which the differences will gradually be eliminated," Einstein wrote. "This representation will rise above the politics of the day."

The scientist, who quit Nazi Germany for the United States, long supported the Jewish community in Palestine. But he had sometimes mixed feelings about the Israeli state that was established during the war of 1948. In 1952, he turned down an offer to become Israel's largely ceremonial president.

(Editing by Alastair Macdonald)