How high oil prices hurt wages and limit economic growth

Loading...

In my view, wages are the backbone an economy. If workers have difficulty finding a job, or have difficulty earning sufficient wages, the lack of wages will be a problem, not just for the workers, but for governments and businesses. Governments will have a hard time collecting enough taxes, and businesses will have a hard time finding enough customers. There can be business-to-business transactions, but ultimately somewhere “downstream,” businesses need wage-earning customers who can afford to pay for goods and services. Even if a business produces a resource that is in very high demand, such as oil, it still needs wage-earning customers either to buy the resource directly (for example, as gasoline), or to buy the resource indirectly (for example, as food which uses oil in production and transport).

It is not just any wages that are important. It is the wages paid by private companies (rather than governments) that are important, as the backbone to the economy. Governments tend to get their revenues from private citizens and from businesses, both of which are dependent on wages of private citizens. There are a few pieces outside of this loop, such as taxes on imports from foreign countries. With the advent of free international trade, this source is disappearing. Another piece outside the US wage-loop is taxes on resource extraction, if these resources are exported.

Instead of using the analogy of a backbone, perhaps I should say that wages are the base that ultimately determines the quantity of goods and services an economy can afford.

Obviously there are other kinds of income, such as “rents,” but these, too, ultimately come from wage earners. Furthermore, businesses cannot earn money to pay dividends unless some consumer, somewhere, can afford to buy the goods and services their business is selling.

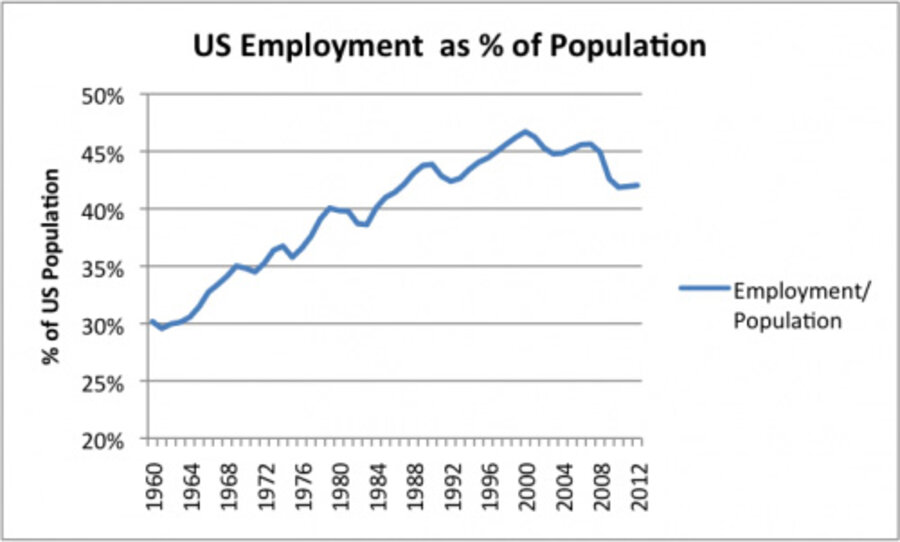

I have written recently about how the proportion of Americans with jobs rose to a peak, and since has been declining.

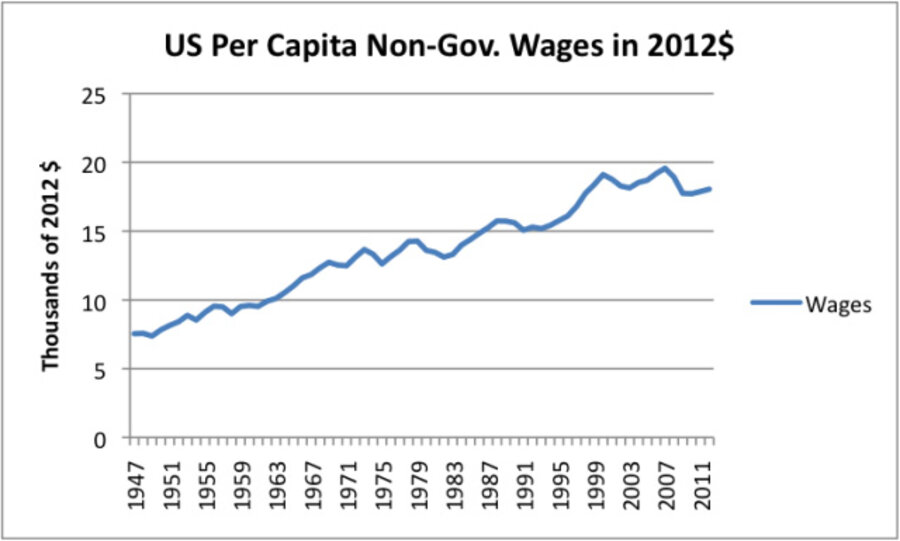

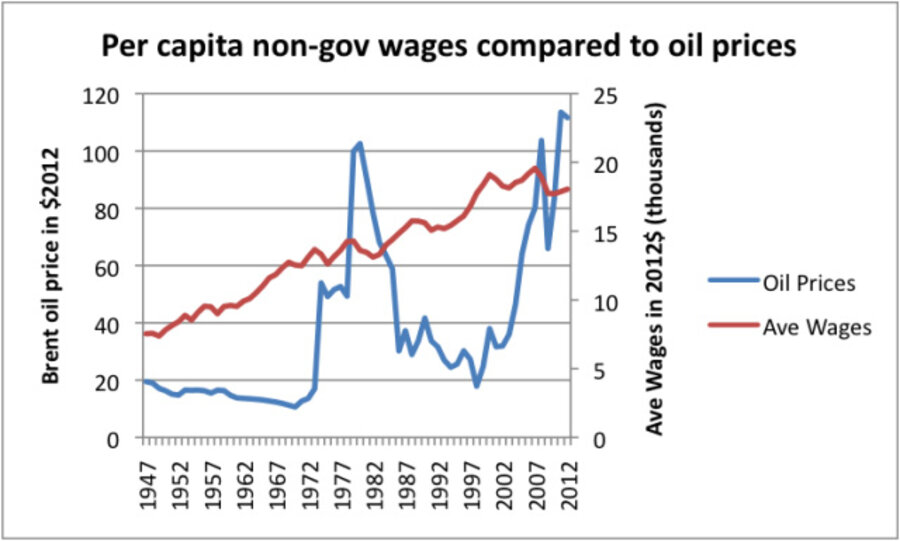

I decided in this post to look at the dollars these workers are earning. In particular, I decided to look at wages, other than government wages, adjusted to today’s cost level using the “CPI- Urban,” cost index of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. I discovered that these wages are doing very poorly. I also discovered a disturbing connection between high oil prices and flattening or declining wages. Putting all of these pieces together suggests a connection to “Limits to Growth.”

Per Capita Non-Government Wages

If we take inflation-adjusted non-government wages, and divide by the total US population (not just employed workers), we get a measure of the extent to which wages have been growing or shrinking. Some of this growth will be from a second wage-earner in a family joining the workforce. Some of this growth will be from families in recent years having fewer children, so that adults make up a larger portion of the population. If some jobs move overseas and are not replaced, this will act to reduce wages.

Comparing Figure 2 and Figure 3, we can see that they follow generally the same shape. A major portion of the increase in wages in Figure 3 is thus driven by a higher proportion of the population having jobs, at least up until the year 2000.

Figure 3 emphasizes how poorly wages have performed since the year 2000. Average wages on a Figure 3 basis hit a high point of $$19,112 in 2000. They then dropped back to $18,145 in 2003. In 2007, they briefly surpassed the year 2000 high point, hitting $19,573. More recently they dipped again and (with government deficit spending) have recovered a bit, rising to $18,053 in 2012. This is very low by historical standards; it is between the level they were in 1998 and 1999.

Looking at Figure 3, the other time when wages were flat was the period between 1973 and 1983. The thing that is striking is that both the current period and the previous “flat” period took place during periods of high oil prices (Figure 4, below). The vast majority of the rise in non-government per capita wages that has taken place has happened when the inflation-adjusted price of oil was less than $30 barrel.

We have discussed previously why high oil prices can be expected to have an adverse impact on wages. There are multiple ways this can happen. For example, oil plays a very direct role in growing and transporting food and in making gasoline. Thus, the cost of food and of commuting increases. This causes people to cut back on discretionary expenditures, leading to layoffs in discretionary sectors. Lay-offs in discretionary sectors means fewer jobs.

Another thing that happens is a change in the competitive situation that indirectly leads to layoffs. Oil is used in transporting many types of goods, and is used in producing a wide variety of products, such as asphalt shingles and synthetic cloth. Wages don’t rise at the same time as oil prices rise. The result is a mismatch between what citizens can afford, and the cost to manufacture and transport products. Some customers are “priced out” of the market. Businesses find that they must scale back the size of their operations to produce only the amount customers can afford. For example, a delivery service will operate fewer vehicles, if demand is lower, laying off workers.

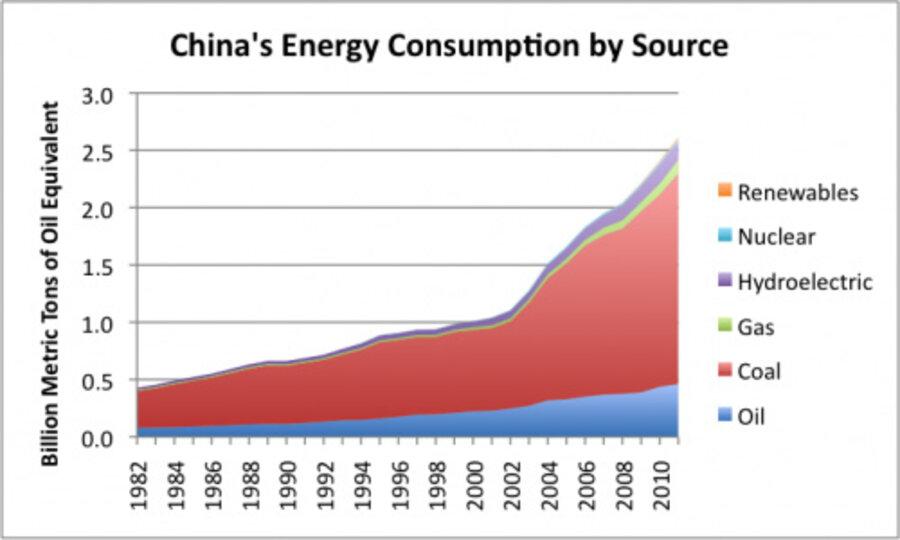

Also playing a role in reduced employment is increased competition from China, India, and other low wage countries. These countries typically use a lot of coal in their energy mix, so are less affected by high oil prices. As a result, their prices become more competitive as oil prices rise.

Changes in trade agreements can also be expected to play a role in the competitive situation. China started growing rapidly immediately after it joined the World Trade Organization in December, 2001. The big drop-off in US employment coincides very closely in time to the time China started growing quickly.

Another factor in reduced wages is increased automation, in an attempt to compete with low-wage countries. An employer may replace several workers with a single worker, using a new high-tech machine. The worker with the new machine may earn more, but the others are left to find jobs elsewhere.

Going forward, increased retirement of “baby boomers” is likely to add further challenges. Retirees will need to be fed and cared for, mostly from taxes on current workers. In theory, the retirement of baby boomers should leave more jobs for unemployed young people, but this will depend on whether such jobs are really available.

One important point is that the impact of high oil prices on wages doesn’t “go away” to any significant extent over time. This is clear from Figure 4, and is a point I have made previously. Increased fuel efficiency helps a bit, as do adaptations like finding a job closer to where a person lives. But high oil prices continue to make goods that are made using oil less competitive on a world market. High oil prices also continue to make increased automation attractive, and continue to keep the cost of transport of high. Individuals find they need to permanently cut back on discretionary spending to balance their budgets.

Oil prices are likely to remain high, and in fact, rise in the future. When we started extracting oil, we began with the easy (and cheap) to extract oil first. Now, the inexpensive to extract oil is mostly gone; what is left is high-priced oil. Over time, the price becomes even higher, as diminishing returns set in. The recent publicity about the possibility of more tight oil in the United States doesn’t change this dynamic. What the press releases don’t say is that this oil will only be available if it is sufficiently high-priced. A recent survey by Barclays indicates that North American oil and gas companies are anticipating less than a one per cent increase in “exploration and production” expenses in 2013; current North American oil and gas prices are not high enough to justify much increase in investment.

Per Capita Real GDP

In recent years, the economy as a whole has tended to fare better than wage earners. This happens partly because deficit spending is being used to provide income to the many unemployed people, and partly because businesses are able to “bounce back” from an earnings point of view better than wage-earners, because they can cut back the size of their operations to keep profits high. Sometimes they can even substitute low overseas labor costs, or automation.

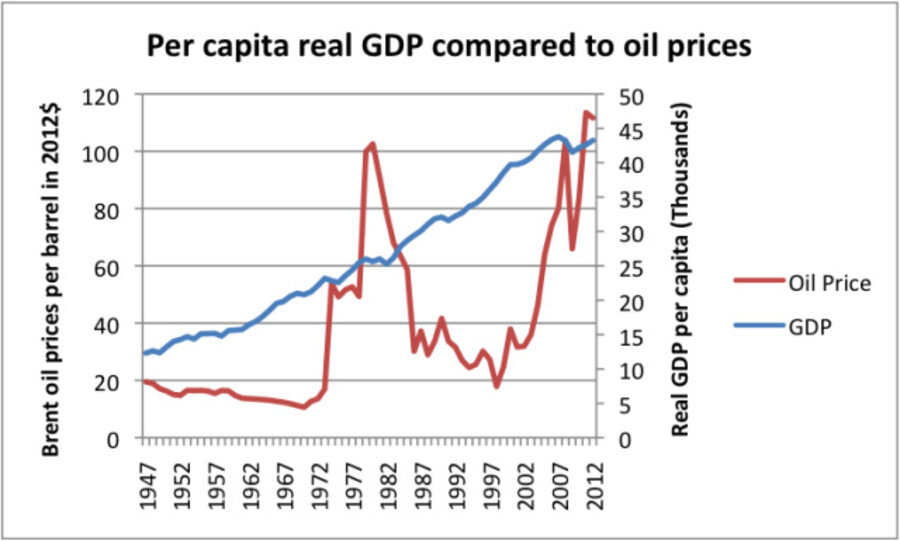

If we compare per capita real (that is, inflation-adjusted) GDP with oil prices (both in 2012$), this is what we see:

There is some stalling in the rise of real GDP per capita, with high oil prices, but it is not nearly as pronounced as the stalling of wage growth. Nevertheless, Economist James Hamilton found that 10 out of the last 11 US recessions were associated with oil price spikes.

On a per capita basis, real GDP per capita in 2012 is between the 2005 and the 2006 level. This is far better than the situation with non-government wages. In Figure 4, we saw that in 2012, non-government wages were only between the 1998 to 1999 level. Ouch!

Hitting “Limits to Growth?”

I wonder if the situation we are reaching now isn’t “Limits to Growth,” as described by the book by that name by Meadows et al. written in 1972. The way we seem to be reaching Limits to Growth is through high oil prices, and the impacts these high oil prices have both on wages and on competitiveness with other countries. I explained some of these issues earlier in this post. There are also impacts on governments:

- Low wages in total mean less tax revenue for governments;

- Fewer employed means more government outlays for unemployment benefits;

- Low wages lead to more problems with debt defaults, and more need for bank bailouts;

- Governments can’t raise taxes fast enough or reduce benefits quickly enough, so they find themselves with rapidly rising deficits. If governments do raise taxes, workers are even worse off. If they reduce expenditures (less unemployment payments or allowing banks to fail), citizens are also unhappy.

Over the last several thousand years, many civilizations have grown up, reached limits of one sort or another, and eventually collapsed. Based on the work of Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov in the book Secular Cycles, there were financial issues not too different from the ones we are seeing now involved in these collapses. I showed in my post 2013: Beginning of Long-Term Recession? that there seem to be significant parallels to our current situation. These collapses often took 20 years or more, but the situation is still concerning.

While the situation we are looking at is unpleasant, if we understand the source of our problems, we can at least look at our situation a bit more rationally. We may not be able to find solutions, but we can at least eliminate some approaches as being unrealistic. We may be able to find partial solutions, such as making survival possible for a subset of humanity, if not everyone. If we don’t understand our predicament, there is no way we can rationally address it.