When London set a new zoo standard

Loading...

Move over, pandas. You're not the first species to make animal lovers lose their minds. Back in the 19th century, hippo hysteria gripped the British people when a hippopotamus from Egypt came to town.

His name was Obaysch, and he was on the husky side.

"A steamship was specially adapted to get him to England, fitted with a 400-gallon iron bathtub. And a small herd of cows accompanied him to provide all the milk he required," says British TV producer and author Isobel Charman. "A specially adapted train carriage whisked him from Southampton to London, and when he arrived at the zoo it caused an outbreak of what can only be referred to as 'hippomania.' There was even a polka composed in his honor."

But Obaysch wasn't there just to be gawked at. The London Zoo, which opened in 1828 as the world's first scientific zoo, was designed to be more than a place for spectacle.

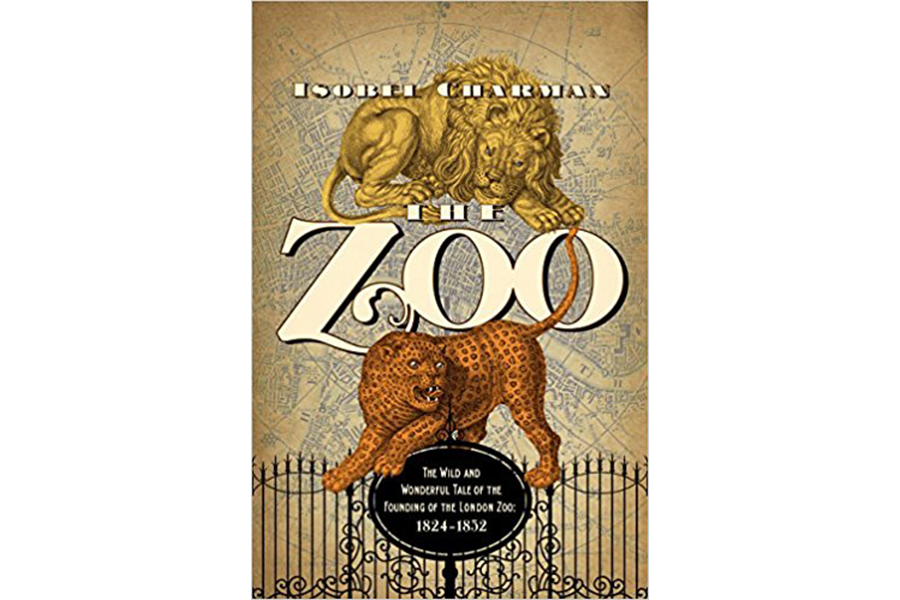

As Charman reveals in her new book The Zoo: The Wild and Wonderful Tale of the Founding of London Zoo, 1826-1851, its creators sought to embrace the serious study of animals. But, as she explains in a Monitor interview, things didn't always go according to plan in the woolly world of captivated humans and captive creatures.

Q: How did people collect animals before the London Zoo was founded?

There was a long tradition of collecting and keeping live, exotic animals. Think back to the Roman era, when wild beast shows took place at amphitheaters.

From the 13th century, exotic animals were kept at the Tower of London in a royal "menagerie." And from the late 18th century, private, commercial menageries also became a common sight in Britain.

The Zoological Society, however, wanted to create a collection quite different than anything that had gone before it. Its aim was to gather animals together for the purpose of scientific study, not prestige or entertainment. They wanted to create a place where the animals could be studied, rather than just gawped at.

A visit was intended to be a new kind of experience, giving visitors the opportunity to see animals in a more natural setting.

Q: How did the zoo's founders and managers balance the interests of the animals and visitors?

From the beginning, there was a tension between the scientific aims of the founders and the need to satisfy the desires of the visitors. The latter often triumphed because the society needed people to keep paying their entrance fees and subscriptions.

The bear pit is a good example of this. It was one of the very first exhibits to be built, designed with a pole at its center that the bears could climb.

Next to the bear pit, one of the keepers’ wives was permitted to run a stall selling cakes and buns, which visitors would stick on the end of walking sticks and umbrellas. They'd encourage the bears to climb the pole and seize them, clearly not a particularly "scientific" exercise, and one that certainly didn’t do the bears any good.

But the visitors loved it, and so it continued. The same happened with the elephant and rhino.

At the same time, the zoo’s first-ever vet was carrying out scientific experiments into the best feeding regimes for the animals.

Q: What are some of your favorite tales about the animals themselves?

One of the most fascinating things for me was how the animals ended in the middle of the biggest city in the world. Many had traveled halfway across the globe to get there.The first orangutan was sent over to London in 1830 along with a leopard. The leopard escaped on board ship and had to be shot, but the orangutan became quite the sailor. He would eat at the dinner table with the rest of the crew and even, so the story goes, take himself to the local tavern when they were in port to get his breakfast.

The first elephant, Jack, arrived in 1831. He had traveled all the way from Madras by way of China and had been cooped up on board ship for many months by the time he was met at the East India Docks. The keepers walked the elephant across London to his new home and had to run to keep up with him. Then were helpless to stop him eating the hats and handbags of the ladies who had gathered to watch!

Q: What is the legacy of the early days of the London Zoo?

London Zoo created a blueprint for a new kind of menagerie, a world away from the circus-like places that had gone before it.That’s not to say it was always successful in achieving that aim. As the decades passed, many of its original aims were left behind, and the quest for ever-more exotic and spectacular beasts took precedence over almost everything else.

Although it’s well over 150 years ago now, the tensions in the zoo’s early years are ones that are still faced by modern zoos today.