How Catherine the Great became an ‘Empress of Art’

Loading...

Russia’s Catherine the Great, one of the most brilliant and accomplished female leaders in history, had plenty of passions. But we tend to remember only the most scandalous ones.

“The popular conception of her is as a woman with many love affairs, including some that were said to be quite curious,” says historian and author Susan Jaques. “That’s where her popular conception ends.”

But there’s much more to this remarkable leader who started off as an obscure German princess and transformed herself into Catherine II, the Empress and Autocrat of All the Russias.

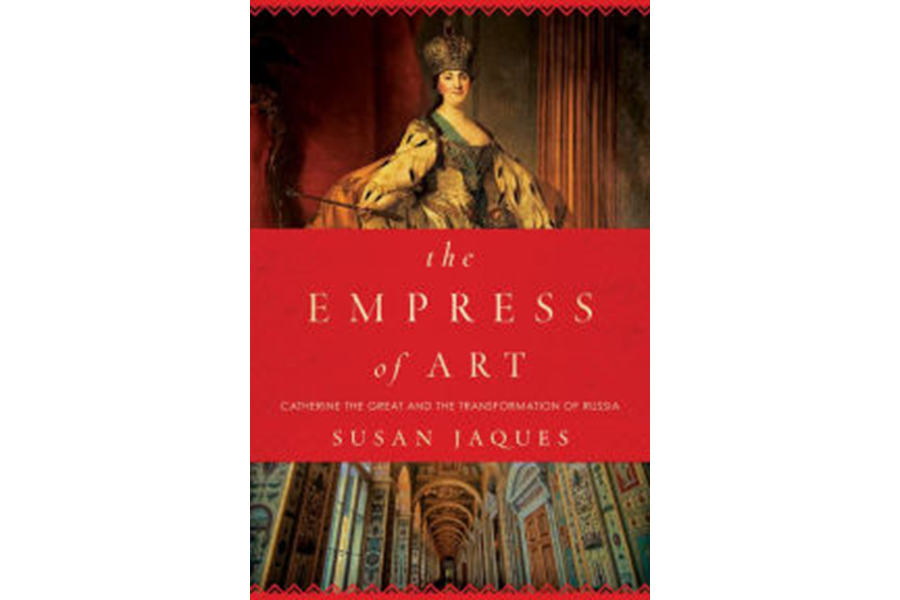

As Jaques explains in her fascinating new book The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia, the 18th-century monarch embraced fine art and architecture as both a diplomatic tool and a source of pride and joy.

A “glutton for art,” as she herself put it, Catherine used European paintings and European-inspired buildings to proclaim Russia to be part of the modern Western world. Her legacy lives on today in the beauty of the city of St. Petersburg and the Hermitage Museum’s famed art collection.

In an interview, Jaques talks about Catherine the Great’s obsessions, her conquests, and her astonishing dual nature. “She’s full of contradictions,” Jaques says, “and it’s those contradictions that make her endlessly fascinating.”

Q: What made you want to explore this part of Catherine’s life?

I’m very interested in art and museums, and I found her absolutely compelling.

Surprisingly, even though Catherine the Great has been the subject of numerous biographies, there wasn’t one that explored her through the lens of art and architecture.

Her art collecting initially started for political reasons, but she actually becomes a knowledgeable and passionate collector, owning 4,000 Old Master paintings. She was as passionate about art as her foreign conquests and love affairs. So this was an irresistible subject.

Q: How did she use art to transform Russia?

She was a minor German princess recruited to marry Russia’s heir at age 15. It’s a very unhappy, miserable marriage. After 18 years, she stages a palace coup and bumps off her very unpopular husband, Peter the Great’s grandson.

She seizes power, and that’s the easy part. She finds herself on uneasy ground because she was German. She has a real problem with her German-ness, so she decides at the very beginning to model herself after her husband’s grandfather, the great Westernizer. She focuses on a world-class collection of Western art and neoclassical architecture, using art to legitimize a very shaky claim and to change Russia’s image.

Q: What was she like as a person?

She was charming and witty, and that led European leaders to underestimate her. She was also a very shrewd, ambitious ruler. She led Russia into two wars against the Ottoman Empire, annexed the Crimean Peninsula, and partitioned Poland out of existence.

In terms of romance, she had about a dozen favorites, mostly younger men, which was considered very scandalous. Even as she was aging, she seems to select younger and younger men.

But while she’s known for this racy personal life, she was rather prudish. She didn’t like people telling off-color jokes, and in art, she didn’t like nudity outside of mythological subjects.

Q: How did she view herself?

She considered herself Russia’s enlightened cultural empress, the empress of the Enlightenment, all about reason and self-control. But she’s obscenely extravagant in terms of her art acquisitions and her building.

She’s full of contradictions, and it’s those contradictions that make her endlessly fascinating.

Q: How well did her efforts succeed?

At the start, Russia was seen as a largely unsophisticated backwater. She wanted to bring herself and Russia prestige by having galleries full of Rubens and Rembrandts and van Dycks.

Over 30 years, she secured some of the top art connoisseurs across Europe – which was very impressive but also very controversial – and was able to amass a first-class art collection.

Through this art collection and by building beautiful neoclassical palaces, she changes Russia’s image. Along with her military conquests, that puts Russia on the map as a cultural center and a military powerhouse.

Q: One of the amazing things about your book is how Catherine comes alive through her letters. What did you learn through them?

She’s a prolific letter writer, and she has lifelong correspondences with some of Europe’s leading intellectuals, including Voltaire.

Her letters reveal her as a very witty, bright and funny personality. She had nicknames for people, not always complementary, and she was funny. She talks about her various art commissions with a sense of humor.

She’s very self-deprecating. That’s part of the public persona she adopted. She’s always the smartest person in the room, and that can be very threatening to men. So she’ll call herself things like “a glutton for art.” In reality, she was a force to be reckoned with.

Q: Was there a negative side to her collecting?

Catherine’s art collection in these palaces didn’t help the Russian people, and she was criticized for not supporting Russian artists, for focusing on Western art. She doesn’t think much of Russian art or Russian architects, with a few exceptions.

Q: What’s her reputation in Russia today?

Her reputation has been rehabilitated over the couple of decades. She’s recognized in Russia as being a very strong leader who expanded the empire and made it wealthy – Russia’s economy boomed during her reign – and left this cultural legacy.

Q: What did she leave behind on the artistic front?

She left her adopted country with an enormous culture legacy including the Hermitage, one of the most beloved museums in the world today, and St. Petersburg, a beautiful and elegant city. That’s to her credit.