Agatha Christie: What one writer discovered in her personal notebooks

Loading...

Call her the unsinkable Agatha Christie. Almost four decades afar her death, the top mystery writer of all time is as vital as ever in our bookstores and on our TV screens.

Just this month, the world's most famous Belgian is reappearing in print in a new Hercule Poirot novel written by a British author with the cooperation of the Christie estate. And while actor David Suchet has just retired from his beloved longtime role as Poirot, new "Miss Marple" episodes featuring actress Julia McKenzie are heading to PBS this fall.

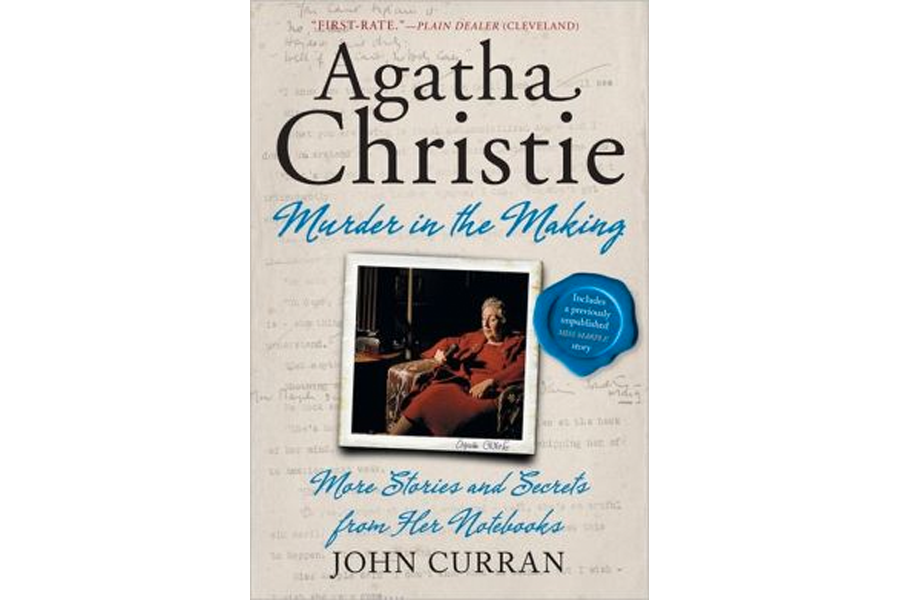

Thanks to John Curran, an author who lives in Dublin, Christie fans have gained tremendous insight into the most mysterious of mystery authors. In 2010's Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks: Fifty Years of Mysteries in the Making, he delved into her surprisingly scattershot approach to developing her characters and plots. Curran followed up with "Agatha Christie: Murder in the Making: More Stories and Secrets from Agatha Christie's Notebooks."

In a conversation, Curran talks about unexpected finds in Christie's novels, the critiques he thinks are bogus, and the surprising chaos of a most intelligent woman.

Q: What are some of the surprises lurking in her books that people might not expect considering her reputation as an old-fashioned "cozy" writer?

An early play has a scientist working on atomic warfare! Gay characters appear, usually non-overtly, in "A Murder is Announced," "The Mousetrap," and "Nemesis," among others.

And there is a dark center to many Christie novels. She did write about murder and love and hate and jealousy and some pretty nasty characters. She does have a child killer, as well as a few child victims.

Q: Christie has critics who don't think she's a literary genius. What do you think of that argument?

She gets adverse publicity about how she can't write like Jane Austen or George Eliot. But all she wanted to do was entertain people while they were reading their books. She wasn't writing deep explorations of the human psyche. She was writing entertainment: I defy you to anticipate my solution. But to make it a more even game, I'll give you lots of clues.

In one of her books, I think it's "Hercule Poirot's Christmas," she names six of her earlier murderers. She thought this was entertainment that would disappear. She had no idea until 10 or 15 years into her career that she was becoming a really famous writer. Or, of course, that her books would continue to be in print throughout her lifetime and 40 years later.

Q: Did you learn anything about her private life by reading her notebooks?

I didn't.

She was paranoid and shy, and she never gave interviews. While she might have a list of Christmas presents or flowers she wanted to buy for the garden, there's nothing of a personal nature in her notebooks.

But I did find as much as will ever be known about how she wrote, about how she planned and plotted.

She had millions of ideas. Even though she produced this vast amount of novels and stories, she still had lots of ideas that she never got around to developing.

The biggest surprise was the fact that she was so completely disorganized in the notebooks. When you turned a page of a notebook, it didn't necessarily follow on from the previous page. The Notebooks were evidence of her wonderful imagination but also of her chaos, and her complete lack of Hercule Poirot's "order and method."

She mentioned in her autobiography that she might have had six of these notebooks. One in her handbag, one in house in Oxfordshire, one in Devon, one out in the desert of Mesopotamia. She'd just open the first page of the notebook that was nearest her. She said all she needed was a typewriter and a steady table.

Q: Is there a less well-known book of hers that you'd recommend?

My favorite of the books that most impressed me is a Poirot novel called "Five Little Pigs" [also known as "Murder in Retrospect"], and the TV version is the best of the David Suchet series.

It's never listed in the same category as "And Then There Were None" or "Murder on the Orient Express." But it's interesting for a variety of reasons. She takes the characters much more seriously, and they're drawn with much more depth than normal.

The setting is her own house in Devon, although that wasn't known at the time. A young woman comes to Poirot asks him clear the name of her mother, who'd been convicted of the murder of her father. He goes back 16 years and asks the five people in the house, the Five Little Pigs, what happened that day.

Another favorite is "Endless Night," which wasn't part of a series. She tells it from the view of a young working-class male, and she wrote it as a 75-year-old who was certainly not working class. She manages quite a lot of surprise in that, and the ending is quite shocking.

Q: What do you think Christie fans should think about when they read her work in the 21st century?

She worked and worked to polish them.

She's a perfect example of the art that conceals art. Everybody thinks because these books are so easy to read, they must be easy to write. If they are, nobody else has ever managed to do so.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.