No one was telling the stories of rural women. So she did.

Loading...

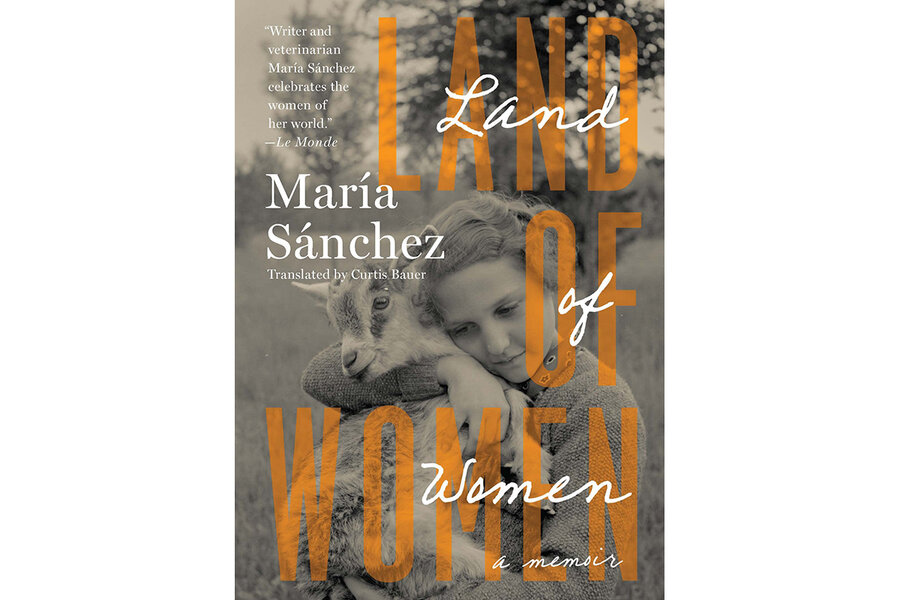

Women who work the land have historically been overlooked in society. Spanish poet and field veterinarian María Sánchez aims to change that in her memoir-meets-manifesto “Land of Women,” a bestseller in Spain since its 2019 publication and newly translated into English by Curtis Bauer, a Texas Tech University professor.

It's a passionate and touching book. The first part speaks to the invisibility of rural women in Sánchez's Spain, but their condition is mirrored around the world. In the countryside, the focus of the community is most often on men, and women give up many of their personal and professional aspirations to support fathers, brothers, and husbands, while also performing domestic duties, working the land, and perfecting their trades. Sánchez argues that rural women are doubly discounted – first in their own communities and then by society at large, particularly by city dwellers who romanticize the work they do, and then belittle them as being uncultured.

Sánchez feels remorse for dreaming about being more like the men in her family than the women while growing up – she would go on to study veterinary medicine like her father and grandfather. She held her mother in contempt for not having grander ambitions. But these were opinions the author held long before she knew what burdens and sacrifices were demanded of her mother. Sánchez recognizes the infinitely important though under-appreciated work of her female family members and other rural women – the behind-the-scenes efforts that hold up families and communities. The author does not seek to glamorize them, nor does she claim to represent every woman. Instead, she strives to give them a voice.

Only by opening our eyes to the innate worth of these women will societies be able to make critical investments to support their welfare and the work they do, the author writes. Their well-being is crucial to the health of not only their communities, but also society as a whole. “Do we value those invisible caring hands and the valuable food they produce?” Sánchez asks. If we do, improvements in land-ownership policies and greater access to education and healthcare will logically follow.

In the second part of the book, Sánchez tells family stories, highlights cultural traditions, and discusses her unique position at the intersection of two worlds: veterinary work and writing. Having a voice, through her writing, is a doubly appreciated gift when she considers that the women in her community, and even within her own family, haven’t always been able to read and write. But as much as the author speaks about herself as part of a “lineage of women of the land,” and thus a valid part of the story she seeks to tell, there is very little of her in this book. It’s likely this was meant as a selfless gesture, to allow women other than herself to be heard and seen, but her absence is felt.

The author also laments humanity’s disconnect from the land, asking, “How can we love what we do not know? How can we protect and preserve what is so unknown and so far away from us?” There are echoes of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass” here as Sánchez encourages the reader to awaken the inner child and reconnect with the natural world.

There’s every likelihood this galvanizing book’s appeal will be wider than expected; it has already been translated into French and German and captured the interest of its eventual English-language translator Bauer while he was living in Seville, Spain. He grew up on a farm in the American Midwest. While reading “Land of Women,” Bauer realized many of the deep-seated problems Sánchez details resemble issues in the United States.

“Land of Women'' may be a small book, but it is mighty. It gives a voice to rural women and speaks truths long hidden. But the power of these women has not diminished by being out of the spotlight. Far from it. As Sánchez writes, “strong species also grow in the shade.”