Frederick Law Olmsted and H.H. Richardson: The design dream team of the 19th century

Loading...

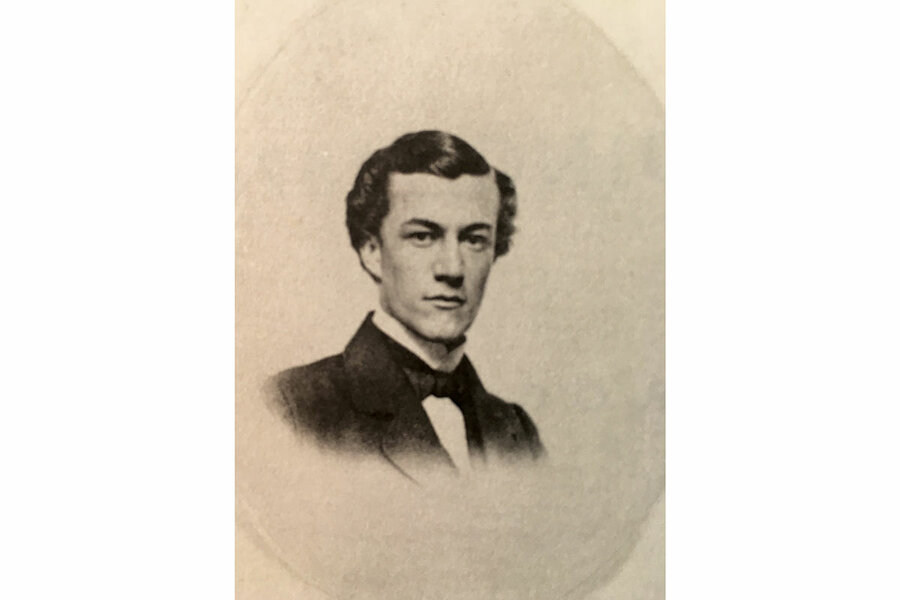

The two men could hardly have been more different: Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted was a taciturn perfectionist, while architect Henry Hobson Richardson was outgoing and well liked. Yet their friendship shaped the direction of American design in the mid-to-late-19th century, and their work influenced the evolution of cities and suburbs.

It’s not clear how Olmsted and Richardson first met. Both men arrived in New York City at the end of the Civil War. Both lived in the same neighborhood on Staten Island and took the ferry to Manhattan each day. Their offices were a minute’s walk from each other’s. But as Hugh Howard writes in “Architects of an American Landscape,” “If their meeting was unavoidable, it was far less certain that [they] would become dear friends. Separated by education and age, they had been on opposite sides of the era’s defining divide. Richardson’s prosperous merchant family had owned enslaved persons, while Olmsted’s voice had been essential in the antislavery movement.”

Still, the two men had much in common. “Each believed deeply in his work. Both looked at the world in three-dimensional terms – or even four-, as times past and future would figure into their designs,” Howard writes. Richardson and Olmsted sensed an opportunity to put their stamp on an America that was rebuilding after horrendous civil strife.

“Architects of an American Landscape” serves as both a dual biography – it tells parallel stories of the two men’s lives – and a detailed survey of their achievements. The book’s extensive drawings, manuscripts, and photographs illustrate projects ranging from Olmsted’s Central Park in New York to Richardson’s Trinity Church in Boston. The men never became partners, but they did collaborate on a series of commissions, including a facility for people with mental illnesses in Buffalo, New York, and a private estate in Waltham, Massachusetts, called Stonehurst.

A Connecticut Yankee

Born into a prominent Connecticut family, Olmsted was a jack-of-all-trades who never attended college. He was a self-taught journalist, wartime sanitary commissioner, mining company manager, farmer, and ultimately, in his mid-30s, the nation’s first landscape architect (a term he and his partner Calvert Vaux invented). After Vaux and Olmsted won the Central Park design competition, the two began their famed partnership on America’s best-known public park in 1858.

According to Howard, Olmsted “was a sentinel warning of a future deprived of the scenic, and he elevated preservation to priority status by inspiring efforts to conserve Yosemite, Niagara Falls, and other unspoiled and dramatic natural scenes.”

Olmsted’s early years as a travel writer, his visits to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in England, and later his summer in the Yosemite Valley made him aware of nature’s profound influence on human emotions. There is perhaps no better example of

Olmsted’s work than The Ramble in Central Park, which gives one a sense of wildness in the midst of the city. His emphasis on nature set the template for the layout of “virtually every suburb constructed since,” Howard writes.

New Orleans raised

Richardson grew up in a wealthy New Orleans family with summers spent on his grandfather’s antebellum plantation. He was a larger-than-life character and a gifted student; at age 17 he left home to attend Harvard, and afterward studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (there were no architectural schools in the United States at the time). Richardson competed against France’s best and brightest at a time when Napoleon III had commissioned Georges-Eugène Haussmann to modernize Paris. The young architect returned to the U.S. in 1865 and established himself in New York City, where his reputation slowly grew.

Buffalo commission

It was Olmsted and Richardson’s shared commission on the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, as it was called then, that would solidify the duo’s combined genius. During the early part of the 19th century, facilities for people with mental illnesses were few and small, and catered to the wealthy. In 1869, New York authorized the building of an asylum in Buffalo.

As Howard points out, “Since the calming effect of nature and the discipline of outdoor work were thought to be part of the treatment of the mentally ill, the grounds of the proposed Buffalo hospital were also important. That meant the commissioners needed a landscape designer as well as an architect.” The Buffalo asylum gave Richardson not only the biggest commission of his young career, but also his first opportunity “to put his head together with Olmsted’s.” The results were a tour de force. Howard describes their team effort as “something remarkable. ... The hospital might have resembled a fortress, but thanks in no small measure to Olmsted rooting it in nature, the safe, therapeutic place would betray no air of incarceration.” The hospital, abandoned in 1974, is now a National Historic Landmark. Parts of it have been restored and repurposed.

After the Buffalo project, Richardson and Olmsted “would soon embark on a series of innovative collaborations that melded buildings designed by the former to landscapes shaped by the latter.”

As their professional lives grew together, so did their personal lives. They built homes on adjacent lots in Brookline, Massachusetts, where their families mingled. And as author Howard concludes, “Their shared understanding of the unfolding panorama of American life in their time informs ours.”