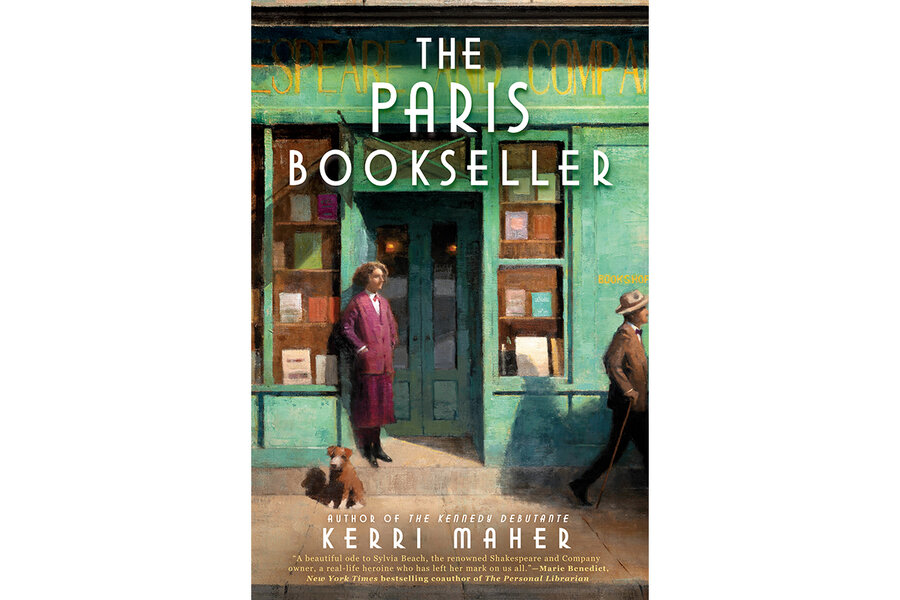

‘The Paris Bookseller’ honors the American woman who published ‘Ulysses’

Loading...

Not long after the end of World War I, American Sylvia Beach opened an English-language bookstore and lending library in Paris. “The Paris Bookseller,” Kerri Maher’s historical novel based on Beach’s remarkable life, imagines her impromptu speech to the war-weary crowd at the 1919 opening of Shakespeare and Company. “Here, a place of exchange between English and French thinking, we get to enjoy the spoils of peace: literature, friendship, conversation, debate,” Sylvia declares. “Long may we enjoy them and may they – instead of guns and grenades – become the weapons of new rebellions.”

The storied Shakespeare and Company, frequented by such Lost Generation luminaries as Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, and Ernest Hemingway, achieved something akin to that hopeful and heady wish; likewise, the charming novel based on the store and its expatriate proprietor expresses much faith in the power of intellectual fellowship.

The central action of “The Paris Bookseller” is Beach’s courageous decision to publish James Joyce’s modernist masterwork “Ulysses” after serialized chapters of the novel are banned in the United States for being obscene. Maher again deploys a military metaphor in describing Sylvia’s passion for Joyce’s work, writing that she sees in “Ulysses” a desire “to explode every protective surface of modern life as surely as grenades had blown up cities and trenches all over Europe.” In addition to her belief in Joyce’s genius, she is also motivated by her dismay over the “stodgy, censorious forces at work in America.”

Maher, who has previously written fictionalized portrayals of Grace Kelly and JFK’s sister Kathleen “Kick” Kennedy, captures the enormity of Sylvia’s undertaking. Joyce delivers scattered pages in barely legible script that must be painstakingly deciphered and typed out for the printer; he also continues revising up until the last moments of the process. When he pleads with her to have the printer change the final three words of the manuscript, Sylvia silently vows that she will “never publish anything else. Ever again. It was too painful.”

Meanwhile, to cover her costs, especially given that she is helping to keep the struggling Joyce afloat, she devotes hours to soliciting subscribers and publicity for the eventual first edition, all while keeping her shop barely solvent. Later, she is enmeshed in costly legal battles with notorious publisher Samuel Roth, who sells unauthorized copies of “Ulysses” in the U.S. after Shakespeare and Company’s edition comes out.

Through it all, the community of French and expatriate writers who congregate at the bookstore drop by to gossip, commiserate, and offer Sylvia guidance on handling her recalcitrant Irish author. These cameo appearances are enjoyable if they occasionally feel contrived.

“The Paris Bookseller” also elucidates Sylvia’s decades-long relationship with Adrienne Monnier, the French bookstore owner and writer whose shop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, inspired Sylvia to open her own. In France, where same-sex relations had long been decriminalized, the two women lived together openly. In 1921, Beach moved Shakespeare and Company across the street from Monnier’s store on Rue de l’Odéon.

Most of the limited tension in this cozy novel concerns the protagonist’s divided loyalties between Adrienne and the demanding Joyce. Adrienne worries that Sylvia will put Joyce’s needs before her own, warning her that “he is a very great writer but not ... a great man.” The two rivals even have warring nicknames for the neighboring bookstores: Monnier calls their share of the block Odeonia, while Joyce christens it Stratford-on-Odéon.

In addition to a reverential rendering of the literary scene at the bookstore, Maher vividly evokes the free-wheeling Parisian social life of the interwar period. Describing a lush celebration at one of the intellectual set’s gathering spots, Le Dôme, she writes, “Under the soft glow of the Dôme’s chandeliers, their group refilled glasses ... and passed around plates of buttery sole and crisp potatoes as the merry clinks of forks and knives against plates echoed off the glass windows and tile floors.”

The novel concludes before the onset of World War II, but the shop was closed and the real-life Beach interned for six months during the Nazi occupation of Paris. Although Hemingway famously “liberated” Shakespeare and Company in 1945, Beach chose not to reopen the store after the war. Her risky publication of “Ulysses” was driven by her faith in its greatness, but she was also savvy enough to intuit that publishing it would confer on Shakespeare and Company its own kind of immortality. (The current incarnation of Shakespeare and Company was later founded by American George Whitman, who named his shop, and his daughter, Sylvia Beach Whitman, in honor of Beach.) “The Paris Bookseller” serves as a welcome reminder of her pivotal role in the history of Joyce’s classic, adding to the affectionate novel’s considerable appeal.