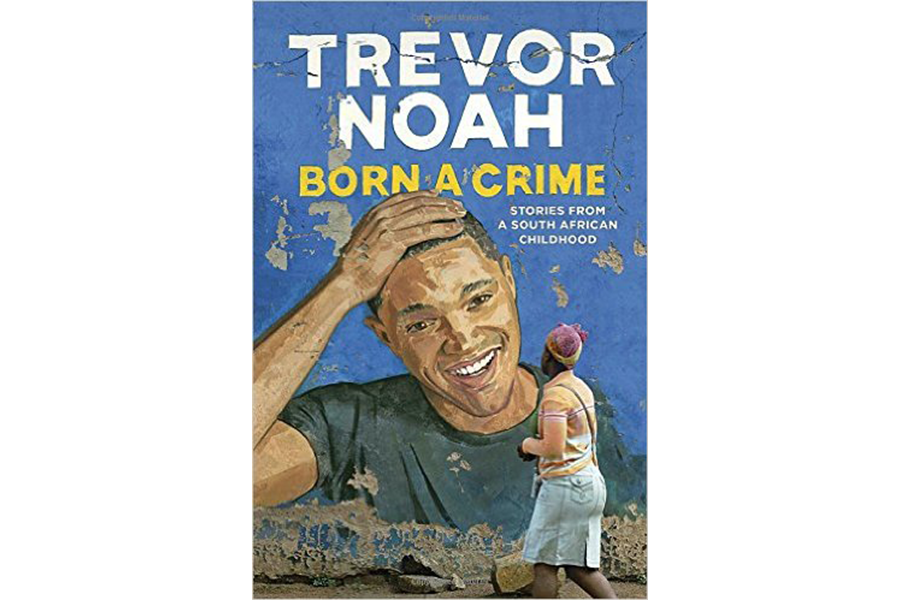

'Born a Crime' is Trevor Noah's tender, rollicking take on his own life

Loading...

We need our comedians now more than ever. The best, from Samantha Bee to John Oliver, were so incisive during the interminable and punishing election season that their work often functioned less as comedy than as vital journalism. There’s a simpler reason many of us need our comedians, too: Those of us who voted blue and are feeling, well, blue will need a way to laugh through our grief and anger as we gird ourselves for the coming Trump administration.

It could be that "Daily Show" host Trevor Noah, the South African comic unexpectedly tapped last year to replace the revered Jon Stewart, will prove particularly adept at wringing satirical humor out of a reality that already feels to many like dark satire. While during his early months in the hosting chair some complained that, as an outsider, Noah didn’t evince Stewart’s impassioned outrage at American political culture, a recent sketch comparing Trump to scandal-plagued South African president Jacob Zuma demonstrated how instructive an outsider’s perspective can be. (Noah made the case that the “inept and self-serving” Zuma and Trump appear to be “brothers from another mother.”) Noah’s new memoir, the rollicking yet tender Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood, provides further indication that Noah’s is a necessary voice for these times.

In addition to that, it’s a great read. The book comprises18 autobiographical chapters, each prefaced by a short piece explaining a relevant element of South Africa’s history of apartheid. Many of the chapters center on his relationship with his fearless and devout black Xhosa mother, who risked a prison term of up to five years by having a child with Noah’s white father, a Swiss expat. Noah was indeed “born a crime,” and for the first five years of his life, until apartheid fell, he was mostly kept indoors, whether with his mother in her Johannesburg apartment or with his maternal grandmother in her Soweto township, to minimize the risk that the government would take him away.

“We had a very Tom and Jerry relationship, me and my mom,” writes Noah, a vivid storyteller who fondly recalls epic chases through the neighborhood as his mother sought to punish him for all manner of mischief and as he sought to escape a beating. As he grew fast enough to outrun her, she took to yelling “thief” to get bystanders involved in the pursuit. “In South Africa, nobody gets involved in other people’s business, unless it’s mob justice, and then everybody wants in,” Noah quips. His writing about his mother is loving and bighearted, especially as she becomes involved in an abusive relationship that culminates in a truly shocking outburst of violence that Noah’s mother, miraculously, survives.

Throughout the memoir, Noah slyly illuminates the absurdities of a society built on racial hierarchy. When the light-skinned child was with his mother’s extended family in the township, he was treated as white. Though he was the least well behaved of all the children, he was never beaten by his grandmother as his cousins were. “A black child, you hit them and they stay black,” she told his mother. “Trevor, when you hit him he turns blue and green and yellow and red. I’ve never seen those colors before. I’m scared I’m going to break him. I don’t want to kill a white person.” While he’s somewhat abashed to admit it now, Noah reveled in his special treatment. “My own family basically did what the American justice system does: I was given more lenient treatment than the black kids,” he reports. “Growing up the way I did, I learned how easy it is for white people to get comfortable with a system that awards them all the perks.”

But when Noah’s mother, who worked as a secretary, was eventually able to buy a home in the suburbs, Noah went from being “the only white kid in the black township” to being “the only black kid in the white suburb.” And although biracial, he was excluded from South Africa’s mixed-race “colored” population, an ethnic group that traces its history back to the 17th century, to the sexual unions of Dutch colonists and African natives. He didn’t quite belong anywhere, and growing up, he had few friends.

The book, focusing on Noah’s boyhood, doesn’t describe his decision to pursue comedy, but one can imagine that a childhood spent as a perpetual outsider, observing group dynamics to determine where he might fit in, has served Noah well in his chosen profession. There were so many times, he recalls, when he “had to be a chameleon, navigate between groups, explain who I was.” He survived it (and writes about it) well; expect him, in the coming months and years, to help explain us to ourselves.