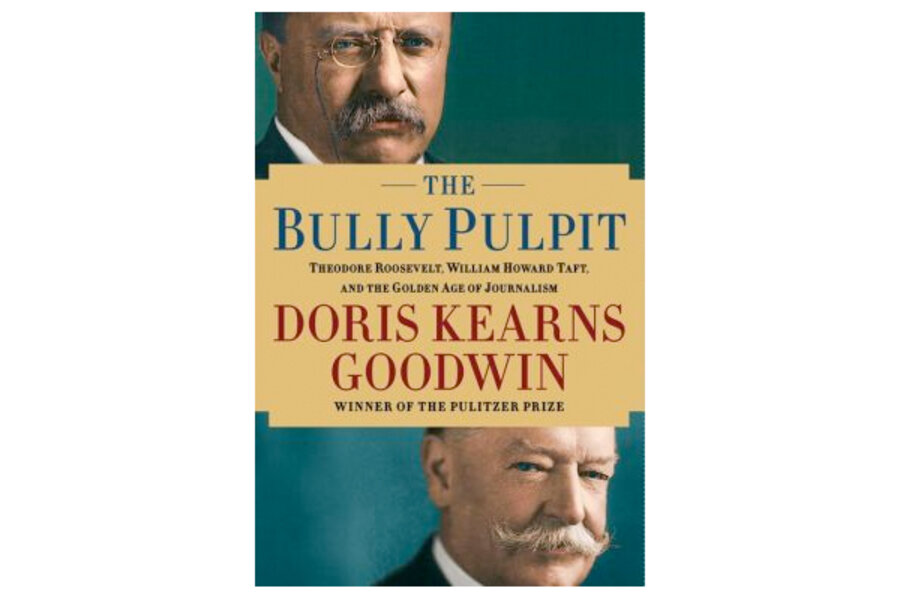

The Bully Pulpit

Loading...

Archie Butt served Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft and died on the Titanic in 1912. Now his story, and many others from the fascinating Progressive Era (which echoes our own times, in many ways), surface anew in The Bully Pulpit, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s well-crafted look at the presidents and journalists who ushered in a brief but significant era of reform.

Before his death, Butt watched with sadness and anxiety as Roosevelt and Taft lost faith and trust in each other. The rift between the longtime political allies weakened the progressive wing of the Republican Party and ushered Woodrow Wilson into the White House in 1912.

“They are now apart and how they will keep from wrecking the country between them I scarcely see,” Butt said as the two men drifted from allies to enemies – and, soon enough, presidential rivalry. Roosevelt’s decision to run as a third-party candidate against Taft, his self-appointed successor, handed the presidency to Wilson.

Their parting and former partnership, along with the role played by muckraking journalists at McClure’s magazine, occupy center stage in Goodwin’s latest presidential biography. As fellow historian Sean Wilentz told the Associated Press in a recent interview, Goodwin has a knack for finding fresh angles to bring her beloved dead presidents back to life.

Her 1995 Pulitzer prize-winning book, “No Ordinary Time,” examined the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt through the lens of his relationship with his wife, Eleanor, and others in his inner circle.

Then came an unexpected obstacle, followed by a triumphant return. Not for FDR, but for Goodwin herself.

Questions raised in 2002 and 2003 about “borrowed material” in two of her books left Goodwin on the defensive regarding the use of passages from other works in what Bo Crader of The Weekly Standard and Slate’s Timothy Noah made clear was more than a one-time, inadvertent mistake. Much of the furor focused on Goodwin's 1987 best-seller "The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys."

In addition, while she credited earlier works in "No Ordinary Time," Noah demonstrated, with authority, the lack of quotation marks for extensive passages in the book nearly identical to the referenced sources. In other words, Goodwin had plagiarized.

All of which made her highly scrutinized return in 2005 all the more remarkable. “Team of Rivals,” Goodwin’s account of President Lincoln and his fractious cabinet, not only put a fresh spin on assessing the most-analyzed president in American history, but was judged to be both rigorous and accurate.

“Team of Rivals” enjoyed an extended run that benefited from rave reviews, an endorsement by a young Illinois senator embarking on a long-shot presidential bid in 2007 (you may now know him simply as 44), and finally, last year, the Steven Spielberg movie "Lincoln." Day-Lewis went on to win an Oscar for his portrayal of the 16th president.

Now comes "The Bully Pulpit," a dual biography of the familiar 26th president (Roosevelt) and the unremarkable 27th (Taft). Goodwin, a familiar face and voice on historical and contemporary politics, has joked in interviews that few Americans know Taft for much more than his 350-pound girth and his custom-made tub at the White House.

Taft loved the law and the courts but fell into politics through his own good character and the constant prodding of his ambitious wife. He and Roosevelt started their friendship in Washington in 1890. Benjamin Harrison named Taft solicitor general soon after appointing TR to the Civil Service Commission. Taft and Roosevelt were neighbors and shared political sensibilities.

Goodwin shows the decency in Taft, particularly during his years as governor general in the Philippines and as a lawyer and judge. Taft became chief justice of the United States in 1921, fulfilling his life’s ambition. No one else has ever been both president and a Supreme Court justice before or since.

To be sure, Roosevelt’s biography is well-told, too. Goodwin hits the high notes in the life of an asthmatic boy who develops into a vigorous outdoorsman, military man, rancher, intellectual, and, of course, a beloved, masterful politician still regarded as one of the greatest in American history. The restlessness and determination of Roosevelt resonate here, from San Juan Hill to speaking softly and carrying a big stick.

Goodwin quotes TR on his own prodigious reading appetites, just one of many examples of Roosevelt’s relentless enthusiasm for so many things in life. “It is surprising how much reading a man can do in time usually wasted,” he said.

And she is wise to balance the stories of Roosevelt and Taft with those of the muckraking journalists led by magazine publisher Sam McClure. Goodwin resurrects the tireless reporters and writers Ida Tarbell, William Allen White, Lincoln Steffens and Ray Stannard Baker, telling of their unlikely rise to prominence and reminding us of how different the media was at the time. Lengthy stories on government policy and influence made the rounds in middle-class America, exciting an audience that swelled as McClure’s grew increasingly influential.

Roosevelt, himself a writer, had thicker skin than many politicos but also understood the value of the Fourth Estate. It was TR, after all, who coined the term “bully pulpit.” In circumstances when he shared the sentiment of the muckrakers, he provided extensive access to allow reporters to unearth cronyism in business and politics.

This stands in marked contrast to recent presidents. Both the Bush 43 and Obama administrations have come under scrutiny and criticism for prosecuting whistleblowers, withholding access to the president and other top advisers, monitoring calls and e-mails of some reporters, and creating an overall chilling effect on reporters' attempts to delve into how and what the government does.

Tarbell and her colleagues faced the wrath of Rockefeller and Republican conservatives but benefited from the aid of Roosevelt and other progressives. Roosevelt opened the first White House media room for reporters and made access a part of his routine. Known as the “barber hour,” Goodwin shares newspaperman Louis Brownlow’s account of the frequent question-and-answer sessions conducted while Roosevelt underwent an early-afternoon shave.

“A more skillful barber never existed,” Brownlow reported. TR “would wave both arms, jump up, speak excitedly, and then drop again into the chair and grin at the barber, who would begin all over.”

The muckrakers emerge in these pages as heroic in their own right, working with Roosevelt and other progressives to shed light on monopolistic trusts embodied by John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil, the lack of regulation for food and other industries, the misdeeds of some labor leaders, and the value of conservation and income equality.

McClure, like Roosevelt, knew the money and influence in Washington (sound familiar?) could only be overcome by popular outrage.

“There is no one left,” McClure wrote in 1903, “none but all of us.”

Goodwin spent eight years working on "The Bully Pulpit" and the effort shows, much to the reader’s benefit and delight. She keeps the story clipping along, chooses enlightening anecdotes (how many Americans knew that Tarbell, who exposed Rockefeller’s ruthless practices in McClure’s, was herself a victim since Rockefeller ruined her oilman father’s business?), and has the narrative and historical acumen to weave her theme through 900 pages. At 70, let’s hope she has at least a couple more biographies in mind, much as her peers David McCullough and Robert Caro, to name two examples, have continued to produce top-shelf work long after qualifying for AARP membership.

For now, savor "The Bully Pulpit." It is a command performance of popular history. Now it’s up to Spielberg, whose DreamWorks has already optioned "The Bully Pulpit" for a movie unlikely to star Channing Tatum and Mila Kunis, to see whether he can match Goodwin’s fine history with a movie of the same quality. In this instance, no one wants to be a trust-buster.

Erik Spanberg is a Monitor contributor.