Robert Lowell and Flannery O'Connor wrote to each other for years, but, as far as is known, the poet's and short story writer's relationship was confined to the page.

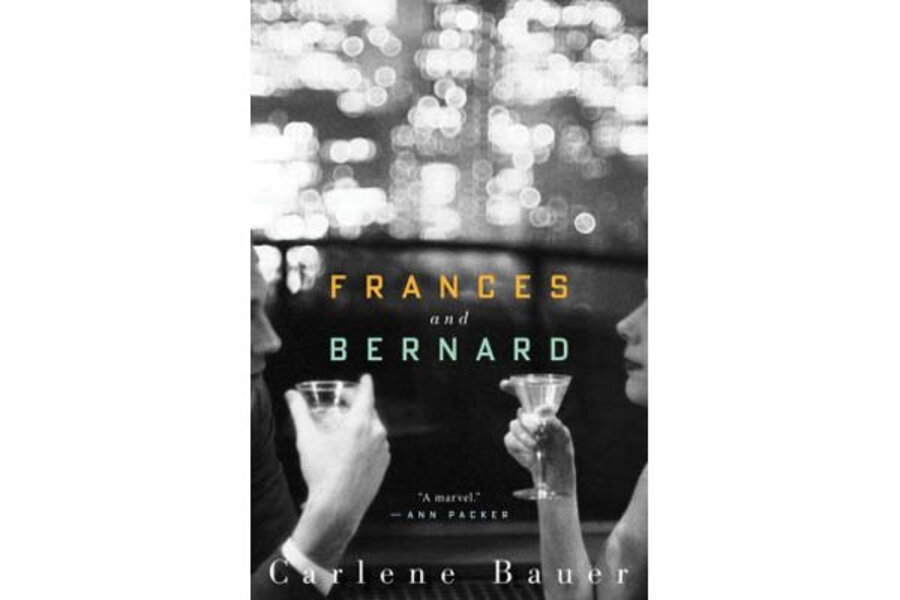

Carlene Bauer takes a romantic “What if?” and turns it into a novel in letters.

In her debut novel, Frances and Bernard, the two write back and forth, starting with religion and going from there.

“Who is the Holy Spirit to you?” Bernard Eliot asks Frances Reardon in his first letter. (Since we know they are meant to be Lowell and O'Connor, this comes off as somewhat less creepy than it otherwise might have. I still would have been feeling around for some pepper spray if asked this after one lunch date.)

The two meet at a writers retreat in the 1950s, where they decide everyone else is a hack. (Lowell and O'Connor met at Yaddo in 1948.)

He tells a friend that he is charmed by her thumping “the bottom of the ketchup bottle as if she were pile driving,” as contrasted with her overall primness.

She decides that he bears scrutiny. “Another poet. But very good. Well, I guess I should say more than very good. Great? I know nothing about poetry except that I either like it or don't,” she writes her friend, Claire. “And his I liked very much. I hear John Donne in the poems – John Donne prowling around in the boiler room of them, shouting, clanging on pipes with wrenches, trying to get this young man to uncram the lines and cut the poems in half.”

The fictional Eliot is younger than Lowell, but he's still a Boston Brahmin, patrician and formerly Puritan, having converted to Roman Catholicism. He is also gripped by the manic depression that Lowell struggled with during his life.

Bauer takes more liberties with Frances – who is healthy and free of the lupus that shortened O'Connor's life. Since those liberties lead to a fictional existence of less pain and not dying at 39, this reader is all for them. Here, she hails from Philadelphia, not Milledgeville, Georgia, a more puzzling change. And Bauer also makes her more conventional -- as with smoothing out Flannery to a more ordinary Frances. A reader can't imagine Frances writing a story about a Bible salesman stealing a girl's wooden leg, like O'Connor did in “Good Country People.” And she doesn't. Instead, she writes about nuns.

Their letters go back and forth, talking about faith and writing and teaching gigs and horrible editors. They both like Superman, can't stand the Beat poets, and bond over Glenn Gould.

“I have taken what I needed from Miss Austen and some Russians and I have packed my bags,” writes Frances, who feels self-taught next to the Harvard-educated Eliot.

While Bernard offers sage romantic counsel, Frances is having none of it. “This is why I won't marry. I am not built for self-abnegation. If I'm built for anything, it's writing.”

This is the pre-feminist 1950s, and for a woman, writing and marriage might truly be an either-or proposition, as Bauer makes clear.

Then the visits begin. Their affair primarily takes place between letters, and Bauer doesn't have them set up his- and-her desks and a joint trophy case. But the more predictable romance is ultimately less interesting than the regard the real-life counterparts held for one another, independent of sex.

O'Connor is quoted as having once told a friend, “As for biographies, there won’t be any biographies of me because, for only one reason, lives spent between the house and the chicken yard do not make exciting copy.” (Of course, there have been biographies.)

But it would have been great to have a novelist prove her wrong.