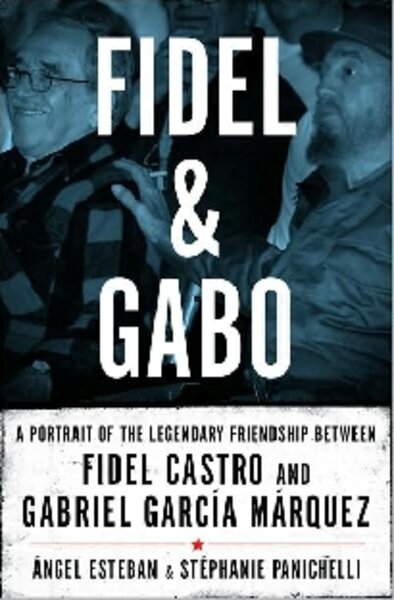

Fidel and Gabo

Loading...

Poets and politicians, oil and water – none of them mix too smoothly. But Latin America’s most famous Nobel laureate and its longest serving dictator have been more than cordial. Gabriel García Márquez and Fidel Castro each count the other as a close friend.

“Fidel is the sweetest man I know,” García Márquez told a journalist in 1977. “Ours is an intellectual friendship. It may not be widely known that Fidel is a very cultured man,” the writer told Playboy in a 1983 interview.

But these were not just book-swapping buddies, professors Ángel Esteban and Stéphanie Panichelli attempt to show in Fidel and Gabo, translated into English by Diane Stockwell. The monograph draws on both previously published interviews with García Márquez and original interviews the professors conducted with sources close to the pair.

Esteban and Panichelli frame “Fidel and Gabo” in a recurring muse-like narrative voice. “You will ... listen in on Fidel and Gabo’s first conversations, when love-at- first- sight quickly blossomed into a strong – and by necessity symbiotic – relationship,” they tell us. Unfortunately, most of the 300-plus pages are a laborious blow-by-blow of who met whom when. They describe literary and political scenes and include historical asides that, while interesting, deviate from the relationship between the title characters. A clear accounting of the friendship between the two elusive figures may just be impossible.

Still, the anecdotes it offers are intriguing. For example, García Márquez has sent all of his manuscripts to Castro before his publisher for decades. Castro read “The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor” and came to the writer’s hotel room to tell him the speed of a boat in the text was not possible, given its arrival time. After that, García Márquez gave Castro an advanced copy of his “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” and Castro said its description of a hunting rifle was incorrect. “I don’t publish any books any more that the Commandant hasn’t read first,” García Márquez told Spanish newspaper El País in 1996.

In fact, one book – a work of at least 700 pages on Cubans’ daily lives under the embargo – never even made it to press, possibly because of the commandant’s objections.

García Márquez engaged in uncharacteristic one-sided reporting favorable to Cuba in several instances, according to Esteban and Panichelli. In a 1977 piece, he portrayed the Cuban military intervention in Angola as a simple act of altruism. His writing on the 2000 case of Elián González, the young Cuban boy whose mother drowned while trying to raft to the US and whose father on the island wanted him back, reads as a “textbook novel” of good versus bad.

“The dramatic oversimplification of life in Cuba found within García Márquez’s writings is beyond comprehension,” the professors say of the Colombian writer’s various reports of life on the island, the earliest of which says that in Cuba there is no unemployment, no homelessness, no hunger. “García Márquez, who in his fiction shuns dull realism and never falls into one-sided, simplistic characterizations, in this instance talks about the good and the bad in absolute terms.”

It was after his favorable reporting from Angola that Castro unexpectedly showed up at the writer’s hotel room in Havana, the first time the leader sought the writer’s company. According to García Márquez, they talked for hours – about seafood.

It appears, however, that the favors did not all go one way. García Márquez pulled his own weight. Several writers say that he arranged for the release of about 3,000 prisoners on the island, though the professors think that number is high. Many families came to the writer to ask for favors with the regime.

So what did each gain from the relationship? Did García Márquez relish being the guarded leader’s confidant, and getting an island mansion near one of Castro’s to boot? Castro surely valued the intellectual prestige that came from the association, since many of García Márquez’s peers had turned against the revolution. If nothing else, the commandant offers excellent material for an author with a penchant for writing about power.

A decent trade, for sure – but it’s too easy an explanation. In addition to everything else, it seems that the two men are, sincerely, friends. “And [Gabo] really does love [Fidel], in spite of his quirks,” the authors conclude.

What’s clearer than the relationship between García Márquez and Castro is that of the writer and the island. His home in Colombia is solemn, he says, and he dreads that. “Cuba is the one place I can be myself,” he told a reporter in 1976.

But that doesn’t mean at ease. It’s well known that García Márquez is followed by at least three “secret” agents whenever he’s in Cuba, say Esteban and Panichelli, who note that, “That’s part of the price of being friends with a dictator.”

Taylor Barnes is a Monitor intern.