The Accidental Billionaires

Loading...

In 2003, author Ben Mezrich – rather like a cool card shark running the table – was on a roll. His bestseller “Bringing Down the House,” about card-counting Massachusetts Institute of Technology whiz kids beating the odds in Vegas, was the basis of “21,” a Hollywood blockbuster produced by Kevin Spacey. And then allegations surfaced that Mezrich embellished scenes and concocted many of the details in his supposedly true tale.

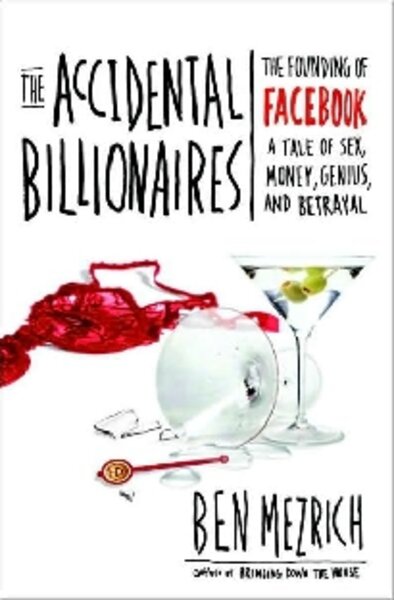

Drake Bennett, whose detailed reporting in The Boston Globe broke the story the week after “21” opened, concluded that “Bringing Down the House” was “not a work of ‘nonfiction’ in any meaningful sense of the word.” So readers may approach Mezrich’s new book, The Accidental Billionaires: The Founding of Facebook: A Tale of Sex, Money, Genius, and Betrayal with some trepidation.

But while they would be right to worry about the truth of Mezrich’s account, a more comprehensive question should stir them as well. Is the ever-evolving Internet, which is transforming almost every aspect of civilization, susceptible to serious historical storytelling? Will the true tale of the Web ever be told?

“Accidental Billionaires” tells the story of Mark Zuckerberg and the creation of Facebook. In an author’s note, Mezrich allows that he invents dialogue, synthesizes details, and puts imagined thoughts into his characters’ heads. Indeed, the resulting book reads like a novel – alas, a generic young-adult novel with crude plotting, cheesy descriptive passages, and grade-school vocabulary.

Clearly Mezrich is no scholarly historian. But despite an emphasis on engaging characters and a compelling story, and despite his self-described immersion in the world of Facebook’s founders, Mezrich’s is a haphazard and clumsy book.

Barely 20 years old, Mark Zuckerberg was a student at Harvard University. He was also an impulsive hacker and an asocial loner, a mystery even to his more socially ambitious friend Eduardo Saverin. Then he turned a dating site proposed by upperclassmen (whose legal challenges continue to bedevil Facebook today) into a social-networking service for students at elite colleges, clumsily rebranding it as “TheFacebook.com, a Mark Zuckerberg Production.”

Recognizing Facebook’s game-changing power, Saverin underwrote Zuckerberg’s project, offering himself as a business partner and adviser and putting money he’d earned as an investment prodigy on the line.

“Accidental Billionaires” follows Mark and Eduardo’s excellent adventure from Cambridge, Mass., to Palo Alto, Calif., through piles of pizza boxes and pages of legal challenges, cease-and-desist letters, and clumsy sexual encounters. Zuckerberg refused to talk to Mezrich; perhaps in retribution, the character at the center of “Accidental Billionaires” is not only a mystery, but also a joke. Allegedly a genius, Zuckerberg here only comes to life when he’s talking to Victoria’s Secret models or planning to crash a ritzy party in Silicon Valley. When he sits down at a computer, when his intellectual and creative juices should be flowing, Mezrich’s Zuckerberg retreats behind a mask.

But instead of being enigmatic, he’s simply boring. Mezrich tells us that Zuckerberg often spent 20-hour stints at the computer, but there’s no hint here what all that coding might have accomplished.

And if the computer-science challenges are mysterious, the motivations are as well. If Mezrich is correct, Zuckerberg and Saverin started Facebook not to take over the world or solve any fascinating puzzles in computer science, but to meet women. Here, the world’s youngest self-made billionaire is merely a cardboard wunderkind with too little grace and too much self-regard, the kind of resentful geek who thinks it’s cool to compare women to farm animals. The supreme irony of his story – that a man so socially challenged would create the Internet’s greatest social network – isn’t mined for the energy and gravity it should yield.

The geeks, dreamers, and tycoons who made the Internet what it is are a fascinating, blockbuster-worthy bunch, but the power of the tools and networks they have built demand serious analysis as well.

Many authors are tackling the story with more interesting ideas than Mezrich brings to bear here. The question is, does the work of the Web itself defy historical accounting? In the end, will there be anything but pizza boxes and faces lit by flat screens? With forerunners like Friendster and MySpace, Facebook turned the wilderness of Web 1.0 into a suburban landscape, settled and domesticated; along the way it changed our notions of identity and privacy as well.

Today, Facebook has more than 250 million users; if it were a nation it would trump Indonesia as the fourth-largest in the world. But sheer numbers are hardly the whole story, for Facebook and its ilk may soon render the concept of nationhood itself obsolete and irrelevant. As their role in the Iran election crisis showed, social-networking sites like Facebook and Twitter are changing the nature of politics, news gathering, and relations within and between societies. The means by which that transformation is taking place are massively distributed and radically ephemeral; whether their substance can be captured archivally and documented by the traditional modes of history remains to be seen.

For his part, Ben Mezrich is too busy snickering about sex and hangovers to wonder what actually went into making this Mark Zuckerberg Production the phenomenon it is today.

Matthew Battles is a freelance writer in Jamaica Plain, Mass. He can occasionally be found on Facebook.