Father and son cooking duo stirs up Chinese cuisine

Loading...

The relationship between Jeffrey Pang and his son, Kevin Pang, was like hot-and-sour soup. It boiled over easily.

The Pangs, who immigrated to the United States in 1988, wanted their son and daughter to know Chinese culture. But as a sarcastic, video game-playing American teen, Kevin wasn’t interested. Learn to make his favorite Hong Kong-style Portuguese chicken, or radish cake for Lunar New Year? Forget it.

Why We Wrote This

Food can bridge divides within families. Cooking dishes from their Chinese heritage, a father and son discover a shared language, and pass on that enthusiasm – with recipes! – to home cooks.

But when Kevin became a food writer for the Chicago Tribune, he realized he had a valuable resource: his wok-stirring dad.

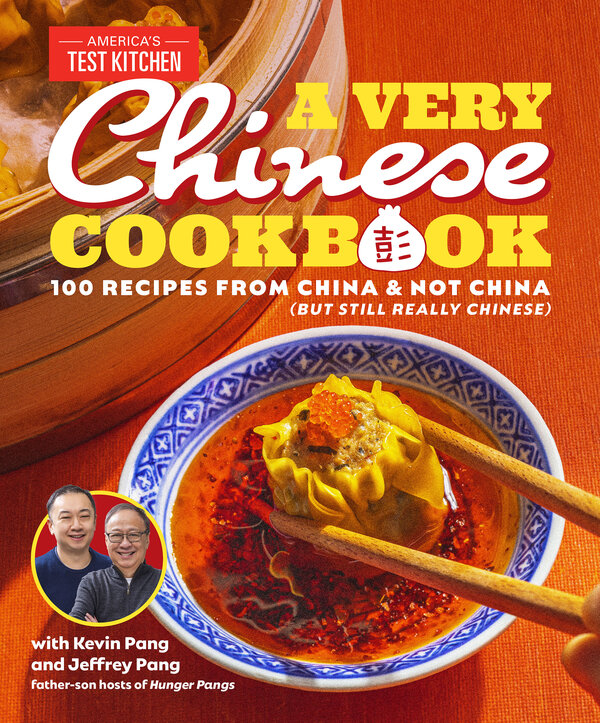

“My father and I shared, for the first time, a mutual interest. I would call to ask about recipes and cooking techniques. He would school me on the world of Cantonese cuisine,” Kevin writes in the introduction to the cookbook he has just published with his dad, “A Very Chinese Cookbook: 100 Recipes From China & Not China (But Still Really Chinese)” from America’s Test Kitchen.

“When it comes to cooking Chinese food, there’s always been this barrier to entry. It’s way easier than people would think,” says Kevin.

Jeffrey says there is another lesson to be found between the pages of their cookbook.

“I think this cookbook can teach fathers and sons how to connect, how to find a common interest and remedy their relationship,” he says.

The relationship between Jeffrey Pang and his son, Kevin Pang, was like hot-and-sour soup. It boiled over easily.

The Pangs, who immigrated to the United States in 1988, wanted their son and daughter to know Chinese culture. But as a sarcastic, video game-playing American teen, Kevin wasn’t interested. Learn to make his favorite Hong Kong-style Portuguese chicken, or radish cake for Lunar New Year? Forget it. Once he left for college, conversations between father and son were brief.

But when Kevin became a food writer for the Chicago Tribune, he realized he had a valuable resource: his wok-stirring dad.

Why We Wrote This

Food can bridge divides within families. Cooking dishes from their Chinese heritage, a father and son discover a shared language, and pass on that enthusiasm – with recipes! – to home cooks.

“My father and I shared, for the first time, a mutual interest. I would call to ask about recipes and cooking techniques. He would school me on the world of Cantonese cuisine,” Kevin writes in the introduction to the cookbook he has just published with his dad, “A Very Chinese Cookbook: 100 Recipes From China & Not China (But Still Really Chinese)” from America’s Test Kitchen.

Comparing notes on food slowly began to shrink the distance between them.

“Cooking is just like a bridge. It helps me pass on my mother’s home recipes to the next generation. That is very, very important to me,” says Jeffrey in a video interview from his home in Seattle.

Chinese food in the U.S. has evolved and adapted since the first wave of Chinese immigrants brought new tastes and cooking techniques to California in the mid-19th century. The cuisine survived the era of chop suey houses and anti-Chinese sentiment brought on by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. It has become a traditional Christmas dinner meal among many Jewish communities and a go-to takeout for busy weeknights. During Lunar New Year – this year from Feb. 10 to Feb. 24 – discovering the delight of soup dumplings is an urban trend. However, many people hesitate to re-create Chinese dishes at home.

“When it comes to cooking Chinese food, there’s always been this barrier to entry. It’s way easier than people would think,” says Kevin, speaking from his home in Chicago. For example, their recipe for cold sesame noodles comes together in 15 minutes using staple pantry items and leftovers.

He is quick to point out that there is no one definition of Chinese food.

“Chinese cooking is not a monolith. The food we grew up eating in Hong Kong, even within China itself, is very different from the food in Beijing, from the food in Shanghai,” says Kevin. “It’s a big tent cuisine.”

For example, consider baked pork chop rice, popularized in Hong Kong.

“It is a pork chop that’s been battered and fried and served with egg-fried rice. And then you top it with this thick tomato sauce that has peas, carrots, and onions,” explains Kevin. “And then you top that with Parmesan cheese. It’s a very interesting hybrid dish that has some Western British influences, and it’s altogether very Chinese as well.”

By the time Kevin joined America’s Test Kitchen staff in 2020 as its editorial director for digital content, his dad had become something of a YouTube sensation demonstrating the family’s recipes with his wife, Catherine. Kevin recognized an opportunity not only to share his own family’s food stories but also to apply the ATK method of breaking down recipes into simple steps for the home cook.

“They really let my father and I be the creative directors,” says Kevin. “It was very much a collaborative process, but at the end of the day, you had two Chinese guys who were able to say, ‘This is what we wanted out of a cookbook.’”

Jeffrey says the rigorous testing at ATK – one recipe can cost $11,000 to test and perfect – opened his eyes to new techniques and flavors, like adding oyster sauce to fried rice. He adds there is another lesson to be found between the pages of their cookbook.

“I think this cookbook can teach fathers and sons how to connect, how to find a common interest and remedy their relationship,” he says. That sentiment has found an enthusiastic fan base, generating nearly 3 million views, for their YouTube cooking series “Hunger Pangs,” where viewers gush over their father-son bond as much as they do over their enticing dishes.

Today the Pangs’ relationship is rarely sour or hot. “We’ve changed to sesame noodles,” says Jeffrey. “Cool, simple, easy.”