Boston scholar finds new Louisa May Alcott writings under pseudonym

Loading...

| Worcester, Mass.

The author of “Little Women” may have been even more productive and sensational than previously thought.

Max Chapnick, a postdoctoral teaching associate at Northeastern University, believes he found about 20 stories and poems written by Louisa May Alcott under her own name as well as pseudonyms for local newspapers in Massachusetts in the late 1850s and early 1860s.

One of the pseudonyms is believed to be E. H. Gould, including a story about her house in Concord, Massachusetts, and a ghost story along the lines of the Charles Dickens classic “A Christmas Carol.” He also found four poems written by Flora Fairfield, a known pseudonym of Ms. Alcott’s. One of the stories written under her own name was about a young painter.

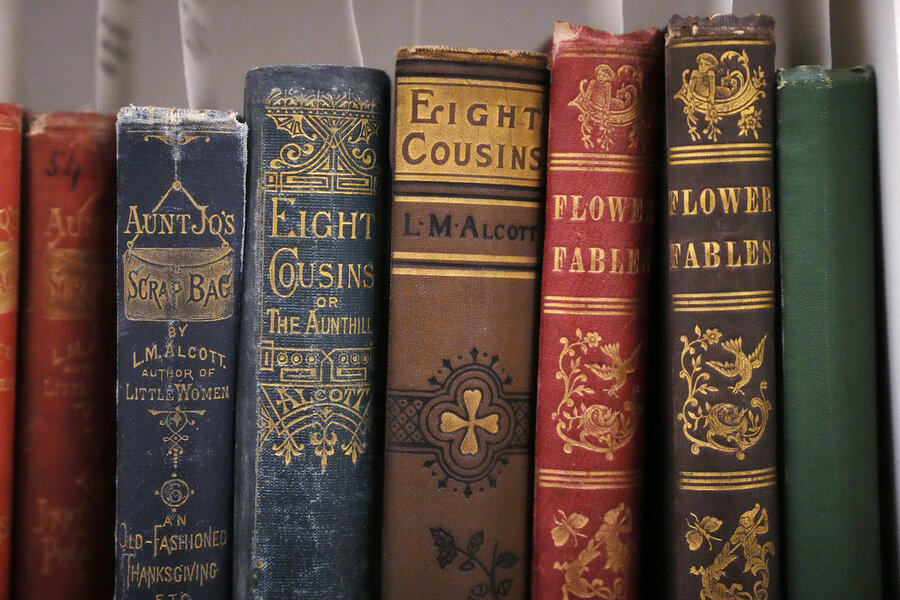

“It’s saying she’s really like ... she’s hustling, right? She’s publishing a lot,” Mr. Chapnick said on a visit to the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, a national research library of pre-20th century American history and culture that has some of the stories Mr. Chapnick discovered in its collection as well as a first edition of “Little Women.”

Ms. Alcott remains best known for “Little Women,” published in two installments in 1868-69. Her classic coming-of-age novel about the four March sisters – Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy – has been adapted several times into feature films, most recently by Greta Gerwig in 2019.

Mr. Chapnick discovered Ms. Alcott’s other stories as part of his research into spiritualism and mesmerism. As he scrolled through digitized newspapers from the American Antiquarian Society, he found a story titled “The Phantom.” After seeing the name Gould at the end of the story, he initially dismissed it as Ms. Alcott’s story.

But then he read the story again.

Mr. Chapnick found the name Alcott in the story – a possible clue – and saw that it was written about the time she would have been publishing similar stories. The story was also in the Olive Branch, a newspaper that had previously published her work.

As Mr. Chapnick searched through newspapers at the society and the Boston Public Library, he found more written by Gould – though he admits definitive proof they were written by Ms. Alcott’s has proven elusive.

“There’s a lot of circumstantial evidence to indicate that this is probably her,” said Mr. Chapnick, who last year published a paper on his discoveries in J19, the Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists. “I don’t think that there’s definitive evidence either way yet. I’m interested in gathering more of it.”

When first contacted by Mr. Chapnick about the writings, Gregory Eiselein, president of the Louisa May Alcott Society, said he was curious but skeptical.

“Over my more than 30-year career as a literary scholar, I’ve received a variety of inquiries, emails, and manuscripts that propose the discovery of a new story by Louisa Alcott,” Mr. Eiselein, also a professor at Kansas State University, said in an email interview. “Typically, they turn out to be a known, though not famous, text, or a story re-printed under a new title for a different newspaper or magazine.”

But he has come to believe that Mr. Chapnick has found new stories, many of which shed light on Alcott’s early career.

“What stands out to me is the impressive range and variety of styles in Alcott’s early published works,” he said. “She writes sentimental poetry, thrilling supernatural stories, reform-minded nonfiction, work for children, work for adults, and more. It’s also fascinating to see how Alcott uses, experiments with, and transforms the literary formulas popular in the 1850s.”

Another Alcott scholar at Kansas State, Anne Phillips, said she was “excited” by Mr. Chapnick’s scholarship and said his paper makes a “compelling case” that these were her writings.

“Alcott scholars have had decades to compare her work in different genres, and that background is going to help us evaluate these new findings,” she said in an email interview.

“She reworked and reused names and situations and details and expressions, and we have a good, broad base from which to begin considering these new discoveries,” she said. ”There’s also something distinctive about her writing voice, across genres.”

This isn’t the first time that scholars have found stories written by Ms. Alcott under a pseudonym.

In the 1940s, Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern found thrillers written under the name A. M. Barnard, which was an Alcott pseudonym. She also wrote nonfiction stories, including about the Civil War where she served as a nurse, under the pseudonym Tribulation Periwinkle.

It wasn’t unusual for female writers, especially during this period, to use a pseudonym. In the case of Alcott, she may have wanted to protect her family’s reputation, since her family had wealthy connections that dated back to the American Revolutionary War.

“She might not have wanted them to know she was writing trashy stories about sex and ghosts and whatever,” Mr. Chapnick said.

“I think she was canny,” he continued. “She had an inkling that she would be a famous writer and she was trying to experiment and she didn’t want her experimentation to get in the way of her future career. So she was writing under a pseudonym to sort of like protect her future reputation.”

At the American Antiquarian Society, a researcher eagerly awaited the arrival of Mr. Chapnick earlier this month. For them, this find is validation that their collection of nearly 4 million books, newspapers, periodicals, manuscripts, and pamphlets is a boon to researchers studying early American history. Many of their holdings are salvaged from attics, antique shops, book fairs, and garage sales.

“We’re keeping these things for a reason. We’re not just keeping them to hoard them and pile them up,” Elizabeth Pope, the curator of books and digitized collections at the society. “We’re thrilled when people can find stories in them.”

For Mr. Chapnick, the collections offer the possibility of finding additional Alcott stories – including those written under other pseudonyms.

“The detective work is fun. The not knowing is kind of fun. I both wish and don’t wish that there would be a smoking gun, if that makes sense,” he said. “It would be great to find out one way or the other, but not knowing is also very interesting.”

This story was reported by The Associated Press.